A structure that ceases to exist can nevertheless cast a long shadow over the imagination. Chicago’s Prentice Women’s Hospital was an example of brutalist (or, perhaps more accurately, brutalist-adjacent) architecture designed by Bertrand Goldberg. Despite multiple campaigns to save this local landmark, it was denied official landmark status and demolished in 2014.

It would not be wrong to read Toby Altman’s latest poetry collection, Discipline Park (Wendy’s Subway, 2023), as, in part, a reenactment of the destruction of Prentice Women’s Hospital. But it would be more appropriate to read Discipline Park as a dismantling of the various economic, societal, and cultural systems that shaped and reshaped the building throughout its lifecycle. In the process of breaking down those materials, Altman clears considerable ground, opening a space that several other subjects in Discipline Park step forward to reclaim.

One of those subjects is the author himself. Altman was born at Prentice Women’s Hospital and has taught at Northwestern University, the institution on whose downtown campus the building once stood. (It is now the site of the Robert H. Lurie Medical Research Center.) Although the demolition of Prentice Women’s Hospital doesn’t entail the death of this textual Toby Altman, it does unmake the means by which he entered the world. Thus dislocated, the poet becomes a kind of phantom: his own Virgilian guide to the afterlife-slash-underworld of late-stage capitalism. Following him proves to be an experience that is, by turns, bewildering, harrowing, edifying, and poignant. Discipline Park is not quite an epic, not even in an ironic sense, but it does ask readers to depart from received notions of what poetry is and can achieve. And, as far as I’m concerned, there’s no question that Discipline Park is an achievement.

The real Toby Altman was kind enough to chat with me about Discipline Park in mid-August 2023. Our conversation occurred via Zoom. As reproduced here, it has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Joe Milazzo: Upon first encountering the title Discipline Park, I thought it must be a reference to an actual district within Chicago. It’s not. But even if the title isn’t literal, it announces itself as something locatable within our shared built environment. How did you arrive at this title? At what point did the title become apparent to you, and how did it contribute to your work-slash-the work itself?

Toby Altman: One thing that’s characteristic of the book, and of the poetics that produced the book, is that it includes a good deal of found and observed language. Some poems include quotations from bus stop advertisements, for example. The title is another example of that. It comes from the name of a now defunct thrift store in Hudson, New York. I thought it was so amazing that somebody would name their store “Discipline Park.” It seemed bizarre to me, and I was captivated by that phrase.

This discovery occurred midway through the writing process. At that point, the book had achieved a certain weight, but it hadn’t quite fully found its shape or form. Choosing that title provided a point of organization which helped me clarify some of what the book was trying to do—or be.

In my mind, the title captures some of the contradictions that the book is interested in, specifically in terms of brutalist architectural practice. Brutalism is an index of the failures of the welfare state. It has this aspiration to care for its citizens, but, in the process of doing so, it dwarfs the individuals who occupy its spaces. In diminishing them, it disciplines them. That conjunction of violence (which is also ecological), discipline, recreation, leisure, beauty—I think that conjunction is something the book is working toward and through.

For some readers, the title is going to bring Foucault into the mix. (And many brutalist buildings do have a sort of prison complex feel to them.) Do you welcome that allusiveness?

Yes. The discipline brutalist buildings administer is not just a limitation or impingement. It’s a constructive or constitutive discipline. It instructs the subject.

Right. Architecture is about pathways, wayfinding, the organizing of behaviors. Titles perform a similar function. And they’re also simultaneously open and closed. Could you talk a little bit more about Discipline Park’s relationship to brutalist aesthetics?

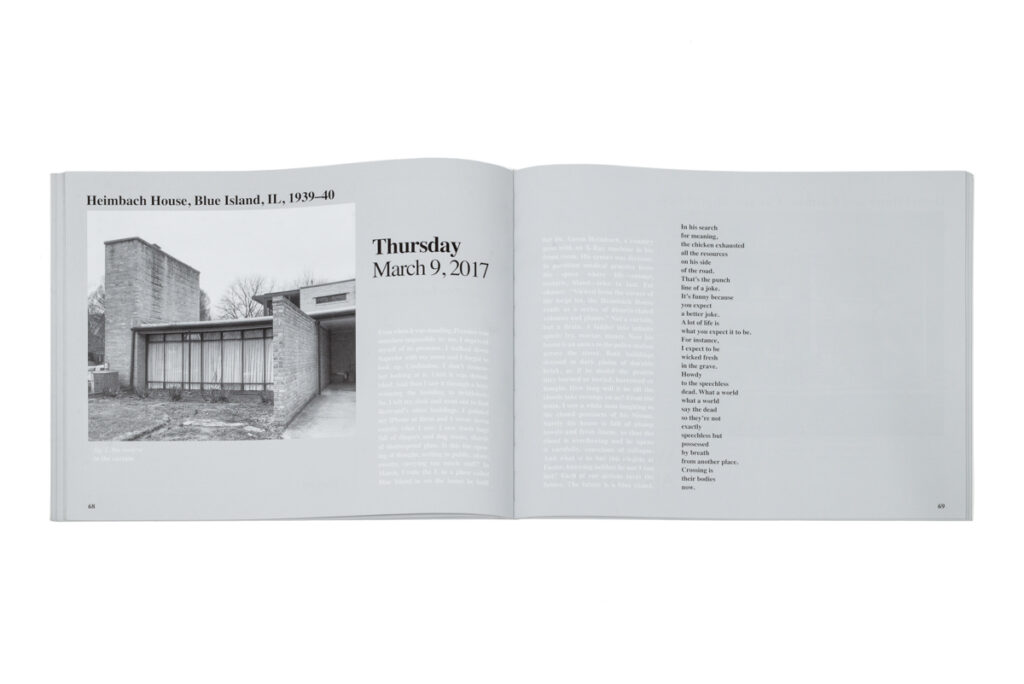

Well, Discipline Park is the first in a series of three books, each of which engages with a different architecture or structure. Each book is an attempt to translate the formal principles of the structure or the architect into poetic principles. But what does it mean to translate architectural or structural principles into poetic form? And how might asking these two art forms to engage with each other transform them?

In the case of Discipline Park, the aesthetics of brutalism were interesting for me to think about, because it’s an architecture characterized by simple, repeated volumes. Many brutalist structures look more complicated than they are. Ultimately, they have one gesture they repeat over and over again, juxtaposing it to itself.

In Discipline Park, I tried to bring that formalism into the space of the page. So the text blocks that appear throughout the book are also simple, abstract material volumes. They permutate, but they still repeat; they’re recognizably versions of each other even if they’re not always identical. This reshaping of a set of very limited spatial or visual possibilities guided the book’s composition.

Do you think it’s accurate to say that even if the forms aren’t particularly organic, their repetition is? Do you feel like there’s an organicism to Bertrand Goldberg’s brutalism in particular?

I think Goldberg is an interesting figure, in part because he’s not really a brutalist. Brutalism comes out of a post-WWII fatigue with the utopianism of modernist architecture. There’s a sense that this utopianism was complicit with the atrocities of fascism. I don’t think Goldberg was necessarily a utopian. He was thoughtful about architecture’s limitations. But I don’t think he ever gave up a sort of utopian vision for what architecture could be. Although he uses brutalist techniques to construct simple, inexpensive buildings, he does so in the service of creating a more democratic architecture—an architecture which is open and accessible to everybody and has the potential to transform society by virtue of its democratic character.

I say this as a prelude to answering your question directly, which is that Goldberg is interested in organic form in a way that brutalist architects generally weren’t. So, his buildings often are modeled on leaves or water droplets. He famously said, “There are no straight lines in nature.” He was interested in creating buildings that embody organic principles. And he worked in a time before curvilinear forms in architecture became banal—and, as Douglas Spencer has argued, characteristic of neoliberalism. So, I like to think that Goldberg’s favoring of natural forms is an anti-capitalist gesture.

That said, I think Discipline Park has a complicated relationship to Goldberg’s project and to Prentice Women’s Hospital in particular. I’m not reproducing his curvilinear forms on the page. My text boxes are very rectilinear. But I am celebrating the ambition of his vision for what design can do and what architecture can accomplish. I wish there were people who shared his optimism. I think architecture would be a better field if it held open more space for Goldberg’s ideas. But he doesn’t appear in many of the central architectural textbooks. He’s a relatively marginal figure, critically, despite how many buildings he built in Chicago. That marginality makes him more compelling because it prompts important questions. Could the history of architecture look different? Could its present?

All that being said, I think it’s also important to mark the failure of Goldberg’s vision. It’s important to explore all the ways in which that vision did not and does succeed in transforming the society it’s operating within. As much as Discipline Park is replicating Goldberg’s architecture, it’s also resisting his aesthetic.

What you have to say raises interesting questions about the relationship between form and intent. Discipline Park is about brutalism. But “about” doesn’t quite capture the extent to which the book interacts with its subject matter. Some of this interaction feels traditionally ekphrastic. But ekphrasis is not, strictly speaking, translation. And I want to turn our attention to Discipline Park’s language. What do you feel happened to your own poetics in the process of writing this book?

Discipline Park is my second book. My first book, Arcadia, Indiana, is very different. It’s a verse play, for one thing. It’s also a different kind of experiment.

With Arcadia, Indiana, I wanted to see if Renaissance poetics could be useful in constructing a twenty-first-century avant-garde literature. I finished writing that book in 2014, and, at the time, I felt like I had pushed that experiment as far as I could. Not that somebody else couldn’t push it further, but I had pretty much exhausted my capacity to work with those materials or find new things to consider.

So, when I set out to write Discipline Park, I was very consciously trying to renovate my poetics, and to come up with a new relationship to writing poems. A big part of my interest in translating architectural form into a poetic form is that it required me to invent a new poetics for myself.

For one thing, the poetics that emerge in Discipline Park are more occasional. The poems are often linked to specific places and times. They’re also more environmental—they’re responding to specific environments. But the poems are also more personal, almost confessional. The lyric “I” enters the work in a way it hadn’t before. Finally, the reference points are more modernist. For example, I was actively thinking about Gertrude Stein while working on Discipline Park as a poetic instance of the kind of modularity and repetition one finds in brutalist architecture.

So, I deliberately sought to shift what my poetics had been doing up to that point. I’ve said this before, but I think it’s true: Every time I sit down to write, I find I’m bored with the poem I’ve been writing up to that point. I want to figure out how to write a different kind of poem. The interest and the excitement that drives my writing often comes from learning how to do something that I hadn’t previously been able or known how to do. Each of the books I’ve written starts with an almost absurd challenge—a constraint I impose upon myself in the hopes of liberating my writing.

I’m glad you mentioned constraint. One of the notes I made while reading Discipline Park was, “Perception is the first constraint.” (Actually, I phrased it as a question only half-rhetorical: “Isn’t perception the first constraint?”) And this notion is connected to the poems in your book being surprisingly personal. The speaker is sharing what they see and, in the process, articulating a vision. But you can’t center the eye in that manner without attaching it to an embodied subject.

Can you talk a little bit more about how you engaged the human sensorium in writing these poems? How much is Discipline Park about the visual field, what it contains, and how we exist within it? To take this line of questioning even further: as you read it, is Discipline Park concerned with the political implications of our species’ strong visual orientation? In my reading, it is.

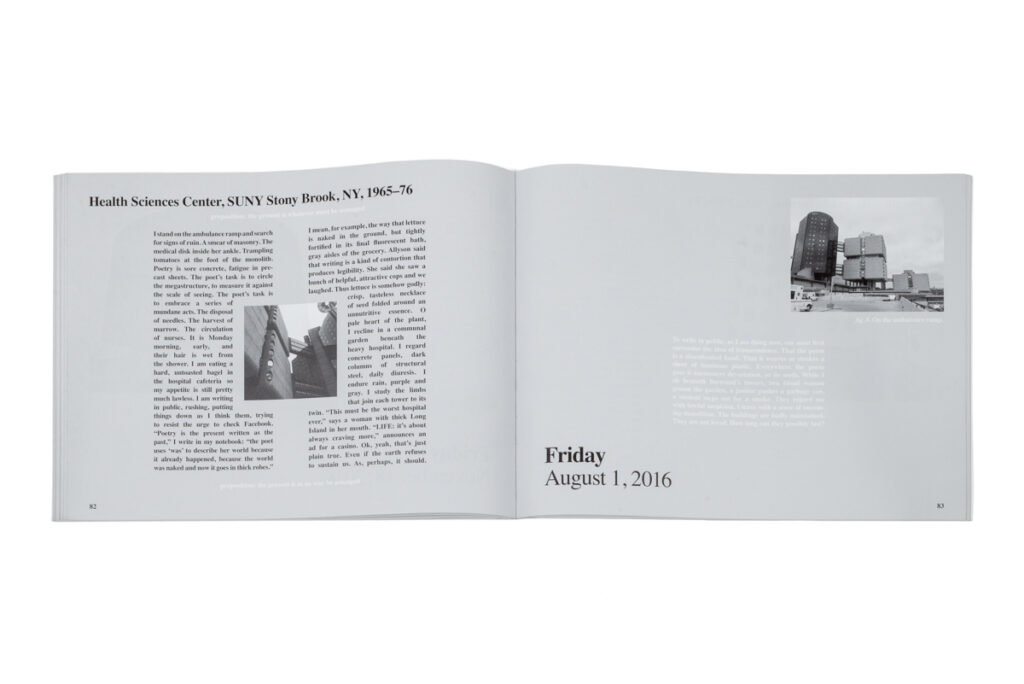

To answer your last question first: absolutely. One of the most interesting aspects of writing this book was visiting Goldberg’s surviving buildings, which I did over the course of two or three years. Visiting an architectural masterpiece is a different experience than looking at a photograph of it. In its presence, you end up measuring the building against the scale of your own perception and the scale of your body. And the building changes and evolves, folding and unfolding, as you walk around it.

So that act of perceiving architecture became one of the subjects of Discipline Park. How do we perceive a building? Moreover, how does our perception itself change whether we’re engaging with the building in this embodied way—sort of face-to-face, as it were—versus a putatively objective or documentary distance: the distance the camera introduces?

That last question is one of the shaping questions of the book. For example, the photos that appear in the first two sections of Discipline Park are all still images from a National Historic Preservation video of the demolition of Prentice Women’s Hospital. I don’t remember ever seeing the building that way. In fact, you would have to have access to a private office in a neighboring building to see the hospital from the same perspective as the camera capturing those images. That depersonalized view of the demolition is simultaneously expressive and constitutive of institutional violence. Meanwhile, the photos that appear in the third section of the book are all photos I took with my cellphone. So, as the book progresses, the act of photographing shifts away from the privileges and permissiveness of an institutional position to the limitations of the human body.

If the photographs in the book’s first section are representative of the state’s point of view, we become aware of that largely through the interventions made within them. Some transformation is occurring within those photos: We zoom in on details; in addition to becoming pixelated, they get divided into discrete units. Grids are either overlaid upon or drawn out of the images. Could you talk a little bit more about what’s happening within those photos?

I read it as a narrative. We’re moving from the building as an integrated whole to the building as a disappeared object. So, the sequence starts with an iconic shot of the windows of Prentice Women’s Hospital, these circular windows with workmen building a scaffold around them—this is a prelude to its demolition—and ends with a shot of an empty lot from which the hospital has been completely erased.

In the second section, all those images appear again. But the space accorded to the image in the first section has been divided in half. And, in the second section, the images begin moving in a way I want to describe as contrapuntal. We start with the empty lot on one side of the page spread and, on the other side, we start with the completed building. We then go backwards and forwards simultaneously. The images are also degrading from page to page. What at first look like little printer’s errors or scratches gradually thicken and obscure the image. The repetition becomes rather chaotic.

I was always interested in testing what it would mean to reproduce this scene of Prentice Women’s Hospital’s demolition over and over again. In earlier drafts of Discipline Park, the images in the first and second sections perfectly replicated each other. But I came to feel like that arrangement created a sense of exactitude that the book isn’t actually interested in. Instead, the book is interested in a poetics of damaged or incomplete repetitions.

Another example of this: in several ways, the book mimics the structure of Prentice Women’s Hospital. The building had four wings and fourteen floors. The book has three sections, each containing fourteen poems. But then there’s a missing wing. The book walks up to the line of exactly reproducing Prentice, then walks back from it. My hope is that Discipline Park’s refusal to present Prentice’s destruction in some unmediated way helps us think about what it means to recirculate images of institutional violence.

Speaking of institutional violence: in her blurb for Discipline Park, Anna Moschovakis writes that the book “brings autobiography, architectural theory, civic history, and an unsettled critique of whiteness to task as it tests the notion that human life is ‘a traveling wound, which inflicts itself on the landscape.’” I want to stop at whiteness. Far be it from me to ask you to disagree with someone who is giving your book deserved praise. But I feel like going deeper into the question of how this book deconstructs whiteness.

For example, portions of the text appear in white on a gray ground. Sometimes, that white text is a quotation from Northwestern University’s press release about the decision to demolish Prentice Women’s Hospital. But sometimes the white text is aligned with an “I.” The context constantly shifts, presenting us with a polyvocal whiteness. I think that’s enough of my observations . . . where is the question here? I think this is it. If Discipline Park is a response to architecture, and bound to a specific building, and that building was built to serve a specific population, then who is Discipline Park meant to serve?

To be honest—and it’s one of the weird things about the temporality of poetry publishing— most of the thinking about whiteness in the book dates from an earlier moment. I was writing poems that made their way into Discipline Park in 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017. Let’s call that a cultural and historical moment. It’s one that’s still with us in a lot of ways. But we were also in a different place then. So I don’t really know how the book’s critique of whiteness lands in the present. Does it still feel pertinent? How has the discourse altered and expanded? It’s hard to say.

But I will say this: I believe that if you’re going to write about urban space, then it’s necessary to think about the relationship between structural forms and structural racism. As Adrienne Brown has argued, the innovation of the skyscraper is inseparable from Chicago’s racism. So, if you’re looking at these buildings, you’re also looking at the world racial capitalism has built. And it’s necessary to say that even if we all feel like we recognize as much.

Goldberg is not innocent in this regard. As a white liberal of a certain generation, he very consciously used different materials and architectural forms in different racial and class-based contexts. His buildings have a complicated legacy. Even as they’re attempting to generate a utopian rupture, they’re still reaffirming racial capitalism. They exist and function within that fabric.

To bring this back to Discipline Park and the larger project it’s part of: one of the fundamental assumptions—or one of the fundamental wagers—that all these books are making is that their “I” is constructed by this architecture. The consciousness on these pages is at least partly a product of this architecture. So, if architecture and the urban space it constitutes is implicated in and affirming of racism, then it becomes necessary to think about how racism structures the speaking voice. That’s all inscribed within the pronoun “I.”

To circle back to feelings: people do have an emotional connection to buildings, and they often grieve when favorite structures are torn down. Maybe it’s the gaping nature of the loss? Maybe it’s just the pain of nostalgia at its most acute? In any event, Discipline Park does deal with or process emotions on that spectrum. One of the first motifs established in the book is an anaphoric “I want . . .” So the book is quite transparent from the outset about the role desire plays in its poetics, and how this desire fuels its ambitions. Moreover, this wanting works against the grain of the cold, institutional point of view expressed elsewhere in the book’s pages.

Can you talk a little bit more about Discipline Park as an emotional experience—how emotion overflows its forms, spontaneously or not? Do you consider the poems confessional (assuming that generic descriptor is not completely deprecated) in any way?

To me, one of the most interesting things about “I want” as an opening gesture is that it implies desire but not success. I wanted that list of things “I want” my poems to do—“I want to write an essay on scarcity. To describe the city as an effect of deletion or decay: a shadow, a graveyard, a series of imaginary islands . . .”—to create a cognitive map of the present (to borrow Frederick Jameson’s terms), a map of all the things that should be described but cannot be. And that includes a cognitive mapping of the ways in which historical forms—architectural, sociopolitical—reinforce each other in the present. I’m not claiming that I’ve completed that map; indeed, the failure to do so is the condition of the book’s speaking.

So from the start, Discipline Park is both articulating this ambition to reckon fully with the world in which we live and marking the impossibility of doing so. And much of that impossibility is emotional. As in, emotion isn’t capable of or up to that task. We can’t feel enough to encompass all the violence of the present. So the book is also about numbness, frustration, impossibility, failure. It keeps coming up against these limits—of architecture, of our present political moment, of its own poetics—and finds them abrasive.

Incorporating so much emotion—so much personal emotion—felt risky to me at the time I wrote this book. I was raised in an avant-garde world where personal expression was very much taboo. That’s what old-fashioned lyric-narrative poets did, right? Write about their lives and their personal experiences? Although architecture informed my formal choices in Discipline Park more so than any poet or poetics, as I was writing it, I kept encountering the work of poets who, while quite experimental in many ways, rely on personal expression and personal experience to create meaning. Claudia Rankine, for example. Don’t Let Me Be Lonely proved to be important to me and this project. Also, Anne Boyer’s Garments Against Women.

I would also single out one book that was important to me and continued to be important to me as I developed the poetics of my next book: Olio by Tyehimba Jess. He’s doing something similarly architectural, but on a much, much wider scale. He opens so many paths for you to move through the poems. Then he invites you to reflect on how and why you’re moving through them in the way you are. Reading Olio empowered me to think about the ways in which I could create a similar multiplicity of pathways for the reader’s eye. When you look at a spread of Discipline Park, it often isn’t clear where or how to start reading. People have found that disorienting at times: what do you do with a poem that doesn’t exist on a page, but across the spine of the book, cantilevered through the negative space that the book needs to sustain its own physical architecture?

More broadly, if I were to make a historical claim, I would say that we’re increasingly seeing a breakdown of that old division between a poetics of experimentation and a poetics of personal expression. Discipline Park is committed to experimentation, and it wants that experimentation to be challenging. But it’s also consciously adopting confessional and memoiristic modes. It’s asking whether and how all of those poetics might coexist. Can you have a poetics full of paradoxes, syntactic disruption, and confession? What happens when all these things share the same space?

I’ll be interested in how readers receive this experimentation—these combinations or recombinations. I do know that some readers feel like the book doesn’t speak with a unified voice. That can been disorienting for them. But that’s great as far as I’m concerned. I’m absolutely against a poetics whose goal is the realization (or apotheosis) of a single voice. I believe poets should cultivate a multiplicity of voice. I’m aiming for that in Discipline Park. There’s many Tobys who emerge here, and none of them are authoritative or authentic.

Yes, the book is full of different registers and discourses. To me, that’s one of the great pleasures it offers. Sometimes it’s mournful. At other times, it’s surreal. And, at other times, so exacting in its self-interrogations I almost want to turn away. But to keep this discussion from becoming too abstract, I’ll build this wrap-up question around a specific passage from Discipline Park.

“Concrete starts life as a messy soup of suspended dust, grits and slumpy aggregate.” It ends as rubble: the point of wreckage that enjambs the river. It rots from the inside. Its weakness is its reinforcement.

We started this conversation by talking about how your project is, in one sense, a search for a new poetics. So I’m tempted to read that passage I quoted as a sort of ars poetica. What is poetry’s relationship to innovation? To posterity? Does poetry have a future? As Joshua Schuster asked several years ago: “What will poetry be in ten thousand years?” It’s a virtually impossible question, of course, but that makes it inherently philosophical (in my opinion, anyway). How do you think about the future of poetry? Poetry in general, if you like, but specifically your poetry. Can it serve as infrastructure? What actual conditions can be built on a foundation of imaginary conditions?

At least eight different answers to this line of questioning come to mind. Let me try to pick one that makes sense.

One thing I’ve thought a lot about in my scholarly work is how, over the last thirty or forty years, poetic innovation has fallen by the wayside. On the one hand, you get this increasingly rote repetition of radical modernism. On the other hand, you get poetic projects that draw their disruption and their novelty not from a projection of the future but by engaging with the past. For example, Robert Duncan’s rewriting of the Metaphysical poets. Experimental it may be, but it’s not avant-garde in a fundamental sense. Duncan isn’t out to burn the libraries, as the Futurists would have put it.

Myself? Over the last decade, my poetry has consistently been in dialogue with historicity: with the past and the aesthetics of the past. I’m constantly thinking about the ways in which the violence of the past continues to be implicated in the present—in the ways that the violence of the past is constitutive of the present. The future that’s ultimately available to us is radically delimited by the violence of the past. All of us here in the early twenty-first century are working with this foreshortened future of anthropogenic climate disaster. And the future looms, in part, because of all the structural and institutional forces that Discipline Park is engaged with.

I don’t know that I’ve answered your question, but I will say this: the moves that have made sense in terms of figuring out what poetry—or even just my poetry—looks like next involves a consistent turning to the past. I’m looking for the image of the future already written within the past, to name that image, describe it, to explore and critique it. Otherwise, I find it difficult to imagine a different present.

Joe Milazzo is the author of Crepuscule W/ Nellie (Jaded Ibis Press, 2014), The Habiliments (Apostrophe Books, 2016) and Of All Places In This Place Of All Places (Spuyten Duyvil, 2018). His work has appeared or will soon appear in Black Warrior Review, BOMB, Denver Quarterly, Fence, Full Stop, Puerto del Sol, Prelude, Tammy, and elsewhere. He is also the Founder/Editor-In-Chief of Surveyor Books. Joe lives and works in Dallas, TX, and his virtual location is http://www.joe-milazzo.com.

This post may contain affiliate links.