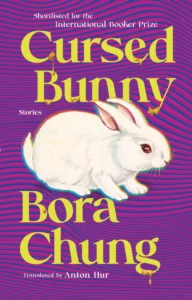

[Algonquin Books; 2022]

Tr. from the Korean by Anton Hur

The year 2022 was tremendously good for the grotesque in contemporary fiction. Mircea Cărtărescu’s Solenoid cloaked a pulsing, animal panic behind layers of philosophizing. Mónica Ojeda’s genre-agnostic Jawbone crawled out of itself like a snake shedding its skin. Missouri Williams’s The Doloriad took a Cronenbergian swipe at religious ecstasy. Fernanda Melchor’s Paradais was a book so visceral that one could practically feel the sweat clinging to its humid, lurid pages.

But among all of this flowering decay emerged a standout: Bora Chung’s Cursed Bunny, which was shortlisted for the International Booker Prize alongside epics, works of Nobel laureates, and runaway BookTok hits. While a meteoric star in South Korea, Bora Chung was unknown in most of the world. Her work had never been translated into English before, and at the time of the prize, the book wasn’t available in the United States.

While the award would eventually go to one of the epics, Cursed Bunny was the only short story collection nominated for the prize that year. In fact, Cursed Bunny may be exemplary among short story collections in general. I am not sure I have ever read one quite like it.

Its creation was almost elemental in its simplicity. As Chung recounts in her Booker Prize interview, Mirror, a beloved Korean website for speculative fiction, decided to do an anthology themed around the animals of the zodiac. As Chung puts it, the “glamorous animals” (dragons, tigers, snakes) were taken first, followed by the familiar, domesticated animals: dogs, pigs, roosters, and rats. Chung, arriving to the anthology a little later, was left with the choice of sheep or rabbit. She chose the rabbit, and was able to give herself some creative room to breathe by simply inverting her subject. If a rabbit is cute and fuzzy, in her hands it would be twisted into something surreal and monstrous. And she delivers on that in spades.

“When in doubt, go against logic and/or common sense,” Chung has said of her process. However, the finished product reveals that this is far too humble an explanation. In these stories, it’s less that she is going against logic and common sense, and more that she establishes entirely new modes of logic and common sense. To read Cursed Bunny is to enter into a game with the author. Chung has little time for window dressing and exposition, and so every story begins in medias res. At no point should you expect the space to acclimate to the world contained within each story; you will have to figure out the rules by which each of these little microcosms abide as they reveal themselves to you. You learn to ride the bike while it’s already in motion.

The stories are extremely agile, often beginning with a grounding in reality, only to swiftly, subtly depart for outcomes unknown—or worse, stories may depict our reality all along, slowly becoming unrecognizable in funhouse refractions. These are stories that often operate by dream logic, making unquestionable sense when viewed from within, then revealing their strange and difficult truths just as the next story careens into view.

There’s a surreality to Cursed Bunny that is ever-present but never distracting. Chung shows brilliant restraint in these stories, never letting a single one overstep its boundaries to break a reader’s immersion, even as they strain against the upper limits of strangeness that could be allotted for each individual premise.

Chung’s writing is taut and sinewy, her confidence is effortless, and the narrative risks—her sink-or-swim approach—pay off again and again, with results that are nothing short of spectacular. For example, consider the first story in the collection, “The Head.” In its opening, we are introduced to a nameless woman and the human head that has suddenly appeared inside her toilet bowl. The head claims that the woman is its mother. She flushes it.

The head reappears, naturally. Her family advises her to ignore it. She avoids using the bathroom until she makes herself sick. The head in the toilet bowl follows her through the pipes, to new houses, and, as her life progresses, begins to ask questions about her children—her real children. This crosses a line for the woman. She plucks the head out of the toilet, mummifies it in plastic bags, and disposes of it like contraband—tossing it, hurriedly and anonymously, in a public dumpster.

She lives the rest of her life free from the head, until one day, now that the woman is old, the head suddenly rises out of the plumbing once more, now dragging a body behind it. The old woman looks at the head, which has now assumed a perfect replica of the woman’s younger face. The head grabs the woman with its new body, shoves her into the toilet, and flushes.

It’s a familial revenge story, ultimately. The head regards the woman as an absent, if not outright cruel, mother. The head was born unwanted, and it had to grow up in spite of its creator. The head then forces the woman into the same conditions that it had endured for so long (the toilet), and assumes her place, her life. The best revenge is living well, as they say.

Chung is a tough but fair storyteller. Cursed Bunny is a book in which everyone gets what’s coming to them, even if they do not know it is coming to them. It’s almost cosmic, a sort of universal retribution delivered unto her characters. It’s as if these stories hover in the moment that the traffic signal turns yellow, signaling danger from the moment they begin, only for the light to turn red at the moment their characters are most vulnerable. Once you have learned the off-kilter rules by which the story operates, you will watch as the characters break them. Consequences ensue, as they always must.

A woman gives birth to an enormous, grotesque blood clot after failing to heed the ominous warnings of her obstetrician. A man discovers an alchemical process to create gold from the blood of his children, and makes himself rich at a terrible cost. A character takes refuge in easy coping mechanisms that ultimately doom her. In these stories, trying to outmaneuver your fate is a fruitless endeavor. Attempting to scheme, grift, or cheat your way into a better life will always condemn you to a worse one.

For example, consider the title story. In “Cursed Bunny,” we follow the story of the avenging party, a family of occultists who produce powerful, magical objects. The family of occultists serve mostly as the frame for the actual story about a former friend of the grandfather’s.

In short, this friend owned a high-end liquor distillery. He was renowned for his spirits all over the country. His spirits were so beloved that one of his competitors, an enormous corporation, sought to ruin him—and succeeded. They smeared his company and his family, spreading rumors about the “industrial-use” cleaning alcohol in their products. His small company is ruined and absorbed into the large company for next to nothing. In the bottomless pit of his despair, the friend, the distiller, commits a murder-suicide (as stated, these stories are dark).

So the grandfather in the family of occultists produces a lamp, shaped like a rabbit, with a switch on the animal’s back that would turn the light on and off when the lamp was stroked, like petting a living thing. The lamp is delivered to the greed-driven CEO of the major corporation, and no one thinks anything of it.

This lamp is the eponymous “cursed bunny,” and it produces a multiplying army of supernatural, spectral rabbits that come out at night and eat everything. They infest the corporation’s warehouses, and eat their stock. They infest the accounting offices and destroy the financial records. And finally, the rabbits spread and infest the homes of the employees.

The story is a gradual crescendo of chaos and ruin, all building toward a truly masterful moment—two one-sentence paragraphs, back to back—that evoke a hot-wristed adrenaline feeling that accompanies the inevitable, like tipping too far back in a chair.

The bunny did not chew up the paper in the house of the CEO’s son.

It chewed up something else instead.

From then on, you can only watch as the story speeds toward its ghastly conclusion.

It all returns to Chung’s mission statement: her desire to completely invert the expectations of her subject. Within the traditions of the zodiac, the rabbit often represents mercy and kindness, and here it offers neither. Outside of the zodiac, the rabbit is often used as a symbol of good luck, hope, and fertility, and in Chung’s hands, it promises retribution, destruction, and death.

It’s not all gloom and doom, however. There’s a playful quality to Cursed Bunny that sets it apart from contemporaries like the gristle and gore of Sayaka Murata’s Life Ceremony, or the creeping uncanny of Samanta Schweblin’s Seven Empty Houses. Instead, there’s a flashlight-under-the-chin exuberance to Chung’s little nightmares, like sitting with friends as they try to one-up the story that has just been told.

Even as the scope of the stories gets larger, their themes darker, and their structures more ambitious, Chung’s principles remain consistent. The language is carefully measured, and deftly translated by the seemingly inexhaustible Anton Hur, who imbues each story with depth and nuance, without sacrificing the coherence of the entire collection. The tones of stories may tilt melancholy: “Every person has only one childhood, and instead of being full of hopes or dreams, his had been crushed by the fight for survival.” Or sinister: “And since the father was working so hard, he thought, the children ought to shoulder some of the burden for the family.” Or most often, they are tinted with a sort of fatal pragmatism: “Life is a series of problems.”

Chung paints each story with similarly hair-raising color palettes, but smartly refuses to limit herself to one structure, subject, or genre. One moment, you may be reading a folktale; the next, you are immersed in a science fiction story with androids. The through-line between them is a slick sheen of menace, and the knowledge that you will find your way out the other side of a story, but always at a price.

It’s rare to encounter something that can so deservedly be called “haunting,” but Cursed Bunny delivers. Each one of the ten stories in Cursed Bunny makes its case for being the standout, only for the next one to hit harder, force you to think bigger, ask deeper questions. Cursed Bunny is a book that asks you to confront your understanding of the way that the world operates. Long after you have completed the book, these stories will follow you—visible only in the shadows, out of the corner of your eye.

James Webster is a writer, reader, and social media person for a small press. He tweets at @exhaustdata.

This post may contain affiliate links.