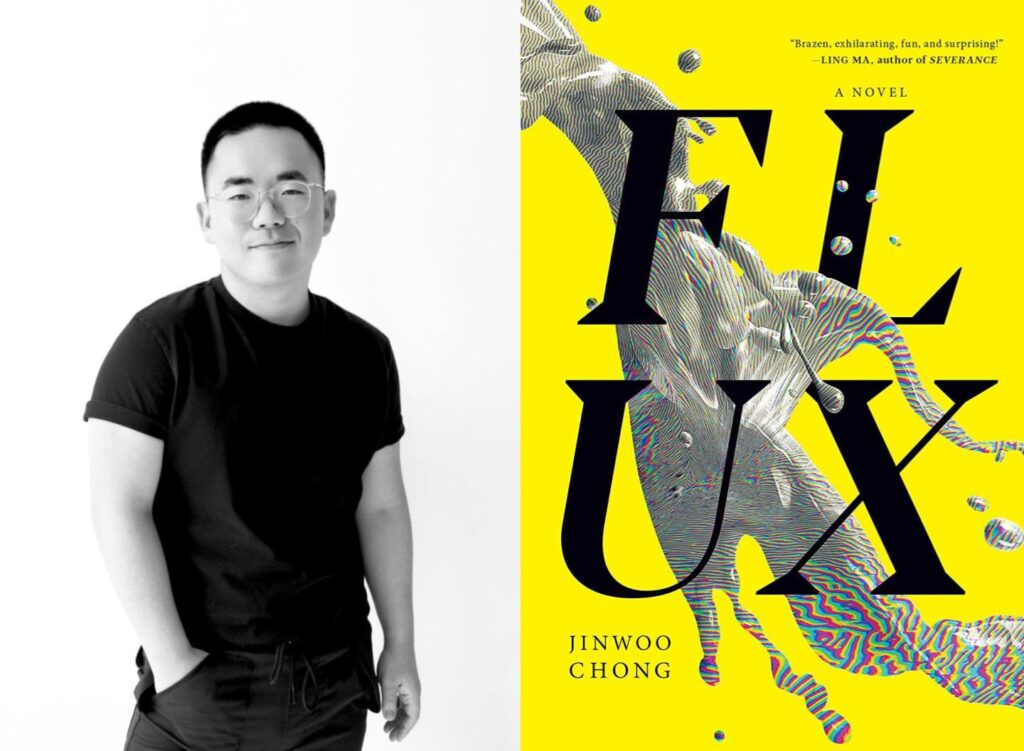

Jinwoo Chong’s debut novel Flux is that perfect alchemy of disorienting and delightful. It’s also a masterclass on aspects of fiction ranging from point of view to structure to building and maintaining an enormous cast of characters to making room for joy. I’ve been enthralled and enchanted by Chong’s fiction since encountering him and his work in 2020, and have been eagerly anticipating his debut ever since. Flux does not disappoint—if anything, reading this novel has only made me even more impatient for his next brilliant work.

Megan Kamalei Kakimoto: Flux is a novel that feels so smartly and intricately plotted. I’m curious about the discovery aspect of writing this book, and if the story’s many surprises were predetermined or if some things came to you simply through writing?

Jinwoo Chong: The process for which I write most everything is to set things forth in an outline that grows and grows, including pieces of dialogue, descriptions, summaries of scenes, research links, etc. The outline for Flux eventually grew into a fifty-page document in two-ish years without ever writing a word of the draft. So the discovery aspect for me took place in the outline, and it reduced a lot of the anxiety when I actually started to write the novel.

Where did the outline begin for you?

I started Flux wanting to write a story similar to Theranos and the fall of Elizabeth Holmes. From there, the outline skewed very literary to a meta-TV show commentary discussing culture and society and how these melded with a futurist examination of pop culture. These all came after I settled on the novel’s initial idea. Then the last piece to emerge was the insertion of the show. Once these concepts were all set in place, I started to write the draft.

Your cast here is enormous, yet at the risk of sounding like a big cliché, I felt all your characters—from the Bo-Brandon-Blue triad to Lev and Io Emsworth to even Raider—as very palpable personalities. Was it a challenge navigating such a large cast of characters? And did Flux begin with one voice for you, or several voices?

I started with Brandon as a sort of fix. I always toyed with the idea of having three narrators in the third person, then quickly realized this would be very tough to execute, especially since these voices in particular are separate but also together. In the end, I felt Brandon’s life in my life most closely, so it made for the most natural first-person voice. The inadvertent side effect of making Bo and Blue third-person was that it feels like Brandon is narrating those two characters as two different people he doesn’t know, which I liked a lot.

This is a hard book, in that it does not shy away from the distressing and the painful, the loss, but I also sense so much joy in both the writing and in the story’s world. Was this a balancing act you were aware of during the writing process?

I really don’t have a palate for total desolation in books. I find myself absorbing the mood of what I’m writing, which bleeds into my life. At some points during the writing of Flux, I found myself very sad for these three characters and what they’ve lost. So maybe as an unconscious decision I worked in these moments of hope or pockets of happiness that saved me from spiraling completely. Those were definitely my favorite scenes to write. For instance, I really enjoyed writing Brandon and Min’s date.

Oh that was such a good scene. The banter!

Yeah they were so much fun to write! It felt necessary because Brandon’s life was already so sad, and it’s hard to portray someone’s innate humanity when they’re just suffering constantly. I felt I needed to give him an opportunity to be compassionate, so people could empathize with him. I didn’t want people to hate Brandon, I wanted them to root for him.

I was absolutely rooting for him. Brandon’s scenes are so compelling, and I’m thinking especially when he starts working for Io Emsworth and Flux and things start to get . . . weird. In these sections we get lots of great repetition that works to foment readerly disorientation. Can you talk about this move to repetition and how you see it working?

That chapter was the hardest thing to write! I wrote an early version in which I realized I was just copy and pasting prose from previous passages. I was trying to strike a balance between a recognizable pattern of repetition while making the writing compelling enough to keep reading—it was really tough. But I wanted to do something like this because the whole idea of the plots being cyclical and intertwining with each other felt very special, and I needed to portray that happening in real time so that it was just as apparent on the line level as on the thematic level. I also tried to think cinematically about this chapter—thinking about sequences in TV and film that portray the passage of time with minute deviations so that you pay close attention to what’s different each time and the disorientation that occurs because of it.

I want to pivot a bit to talk about Korean American identity, and how common it is for writers writing even slightly beyond the traditional white male experience to be saddled with expectations to flaunt their otherness. Throughout my reading of Flux, I had in my mind Carl Phillips’s line about writing “from a self for whom race, gender, and sexual orientation are never outside of consciousness—that would be impossible—but they aren’t always at the forefront of consciousness.” Does this resonate with you at all? And do you have an idea of how you want this book to be read?

The truth of what Carl Phillips said comes into conflict sometimes with our will as children of immigrants, people who are biracial, or have mixed identity, because sometimes you don’t want to think about this part of your identity, while other times you might want to embrace it. I often waver between the two in my personal life, because it’s uncomfortable one way or another. And I feel I have this in common with Brandon. After his Korean mother dies, he rejects this part of his identity even though he returns to it after he has his daughter with a Korean woman. That’s the toughest thing I feel for anyone who is trying to hold two worlds in their life at the same time, because a lot of the time I don’t feel I belong in either America or South Korea (which is where both my parents are from). That kind of lack of belonging can feel very isolating. At the same time, immigration begets a sort of synthesis that creates something that is of neither world but is something new. This is where I find some of the joy and celebration of who I am.

I come from a very white MFA environment in which everyone who is a person of color encounters this question of, do you flaunt your otherness or do you suppress it? And it’s really confusing at times. It creates a sort of cascading doubt. Maybe by writing this novel and having Brandon confront the question, I was trying to inspire myself to do the same. And maybe admit to myself there isn’t really an answer, and I just have to do what serves me in the moment.

Selfishly, I want to know about your influences. Not only whose work inspired you during the writing of this novel, but also whose work really fuels you as a writer.

My favorite book of all time is The Sympathizer, which I feel like borrows its main character from Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison. Both characters are sort of uncharacterizable, purposefully faceless, they don’t fit in anywhere, no one is able to define them, their names do not exist—I fell in love with this kind of character and really tried to model Brandon off of this. I’ve also been a major fan of Ling Ma (reading Bliss Montage was a transformative experience). She does this millennial apathy so well in a way that’s haunting and honestly terrifying.

Also Interior Chinatown by Charles Yu. It was so experimental, and the form was like nothing anyone has ever seen before. There’s a passage in it about why John Denver’s “Take Me Home, Country Roads” is so resonant with old Asian men who sing karaoke, and it was so beautiful to go back and realize the poetry of that song is about yearning from home, which is something immigrants do, except their home doesn’t exist anymore. Even if they were to go back, they’re an other there, because they’re “Americans” now. The theme of what this hits upon really resonated with me while writing Flux, and also as I live my life.

Megan Kamalei Kakimoto is a Japanese and Kanaka Maoli (native Hawaiian) writer from Honolulu, Hawaiʻi. Her fiction has been featured in Granta, Conjunctions, Joyland, and elsewhere. She has been a finalist for the Keene Prize for Literature and has received support from the Rona Jaffe Foundation and the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference. She is currently a Fiction Fellow at the Michener Center for Writers and lives in Honolulu. Her debut collection Every Drop Is a Man’s Nightmare is forthcoming from Bloomsbury.

This post may contain affiliate links.