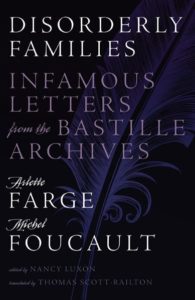

[University of Minnesota Press; 2016]

[University of Minnesota Press; 2016]

Trans. Thomas Scott-Railton

Disorderly Families is a book of stories that were never meant to be told. Its myriad authors spoke, as compilers Arlette Farge and Michel Foucault say, only “so as to not be spoken about,” appealing directly to the head of the infant Paris police force and even the king of France himself to lock up their own relatives. They wanted it quick and quiet, all the better to save face in the eyes of neighbors, authorities, and the crown despite the infamies of their unruly spouses and children.

This is the book’s first and most consistent allure: the reader becomes voyeur, witness to dirty laundry kept from airing for almost three hundred years. These letters culled from the Bastille archives and now translated into English for the first time open windows — sometimes disarmingly wide, more often maddeningly slight — into the homes of the eighteenth-century Paris underclass, and through fluttering curtains and flickering candlelight we see those disordered families rent by alcoholism, libertinage, madness, theft, and violence. Just as we look in, those morose epistolarians look out into the the rat-warren streets of pre-Haussmanized Paris where their wayward sons, daughters, husbands, or wives disappear to pursue their crimes under a nighttime pall uninterrupted by the streetlights and more effective police patrols of later centuries. Following our authors’ multiplied gaze, we see them emerge in turn: “swindlers, troops of undisciplined soldiers, beggars, women of chance, accomplished thieves, heads of gangs, and poor wretches — they are all here,” write Farge and Foucault. They thread in and out of the skein of narratives that makes up Disorderly Families. Not an uninteresting tableau.

Thomas Scott-Railton’s conscientious translation of over one hundred cases of requests for lettres de cachet (“letters of arrest”) makes up the lion’s share of Disorderly Families. He notably leaves their jagged shifts in register intact, particularly between the letters’ flowery formalisms often wrought by paid scriveners and their authors’ frenzied, caustic accusations and demands for justice. According to Farge and Foucault, an attentiveness to contrasts like these is essential to revising our understanding of lettres de cachet and those who requested them. The authors hereby take aim at the still-prevalent view of the lettre de cachet as associated solely with the autocratic abuse of power and top-down social engineering in the pre-Revolutionary period: considered primarily as the king’s way to bypass normal juridical proceedings and imprison individuals through incontestable royal fiat, the lettre de cachet’s most cited victims are invariably those who dared trouble the crown’s political and moral order on the grandest of scales. Denis Diderot, the Marquis de Sade, and Voltaire are among this distinguished band.

But Farge and Foucault’s presentation of their findings in the Bastille archives provides a much-needed corrective to historians’ hitherto single-scale, unidirectional perspective. Put bluntly, common people requested lettres de cachet at a much higher rate than the crown used it on its enemies. What’s more, common people requested sovereign intervention to the end of imprisoning their own family members to a degree that historians have never truly appreciated. What this reveals is an imbrication of public and private spheres at such a degree that “an entire chain of political authority [had become] entangled with the threads of daily life” in pre-Revolutionary France. At a more general level, Farge and Foucault write, “the quite singular practice of the lettres de cachet . . . offers an opportunity to illustrate the concrete functioning of a power mechanism. Not, of course, as the manifestation of an anonymous ‘Power,’ oppressive and mysterious, but as a complex web of relationships between multiple partners.” In a word, Disorderly Families shows that power does not work in one direction or reside in one place — not even under the radically centralized, absolute monarchy of the Bourbons. Even the illiterate and indigent toilers of the Parisian underbelly found sophisticated ways to manipulate sovereign authority to private ends through carefully crafted representations, through staging plays of ceremonial tribute owed to authority, evidence attested by neighbors, employers, and priests, and deeply personal lamentations over justice thwarted and love spurned.

In some cases the direct (and often brutal) intervention of royal authority in these family disputes sees troubles dealt with and order eventually restored. In others divisions only deepen and competing narratives grow more confused, with exasperated police investigators leaving inquiries inconclusive and houses divided. In the majority, however, there is simply nothing. A hole in the archival record or a simple collapse of correspondence abruptly shuts the window and leaves us only to wonder how this or that story — this or that life — played out. Maybe Michel Pierre Corneille, journeyman woodcarver of Faubourg Saint-Antoine, made up with his allegedly debauched wife. Maybe she was taken to the Salpêtrière prison to live out her days in darkness. We can never know. But then — and there will be more on this idea soon — that’s part of the point of Disorderly Families.

Editor Nancy Luxon writes that on the whole, this work “should be understood less as theory applied or as a one-off event than as a window onto the period preceding the Revolution.” Readers did in fact wonder after its initial French publication in 1982 why Foucault even wanted to open this window, and why he did it in this way — in the context of the Foucauldian canon, that is, this book at first seems like a “one-off event” or even a fluke. Foucault after a long period of silence promised a sequel to the first volume of his monumental History of Sexuality (1978) and, as Farge notes in her 2014 afterword, “a collection of texts on a different subject from that announced did not bode well for its publication.” Neither did her involvement — Farge, a historian, remarks on the “quite tense” atmosphere between historians and philosophers in French intellectual culture at the time (no doubt exacerbated by the perennial disciplinary irreverence of philosopher-historian Michel Foucault himself) while Luxon more directly cites leading French academics’ suspicions regarding Foucault’s “collaboration on this volume with a female unknown.”

Beyond the trouble of navigating readers’ expectations and boys-club (read: sexist, however veiled) academic politics, Disorderly Families had another issue: nobody knew what the hell it was supposed to be. With Foucault’s name on the cover, one would likely expect a protracted work of highly provocative, original philosophy. Readers of the original publication were thus first disappointed by “too much text and not enough Foucault,” and second by what that text taking Foucault’s place was. The commentary on the part of the authors whose names are on the cover is limited to four brief essays explicitly aimed at introducing, framing, and drawing preliminary conclusions from what seemed (and perhaps still will seem to some readers) like a hodge-podge of loosely related letters from what could be called “historical unknowns” divided into the categories of “Marital Discord” and “Parents and Children.” But the decision to simply transcribe the letters and keep commentary to a minimum was one arrived at after much consideration and, as can now be gleaned in retrospect, followed a very specific philosophical strategy.

Farge gives us the key to this final point in the Afterword:

Increasingly attached to the beauty of these texts no doubt, to their odd manner of beginning with sumptuous phrases addressed to the sovereign, before continuing with remarks penned by the public letter writer, which had been whispered in his ear, Michel Foucault contended that it was necessary to publish the archives, the dossiers of requests for imprisonment, without any commentary, so that all that remained visible was the “sublime” of these unraveled lives laid bare in hatred and grief alike, facing a sovereign who shone as bright as the sun.

The “sublime” weaves through the work of both Arlette Farge and Michel Foucault in and beyond Disorderly Families, not unlike (and perhaps because of) how those long-dead infamous women and men weave through the texts of little-documented history: fragmented, expressed in the silences of archival lacunae as much as in their momentary screams for love, justice, and mercy. It’s the feeling of confronting what you can never wrap your head around — a mountain, a poem, the infinite depth of the person sitting next to you — and shivering on the precipice of . . . well, the precipice of whatever that is. Arlette Farge saw the sublime in a packet of golden seeds tucked into a folder in the Arsenal archives, an experience she relates in the magisterial Allure of the Archives (2013), also recently translated into English. Foucault talked about it when attempting an answer to the question “What is Enlightenment?” in 1978. While accused of sentimentalizing the “poem-lives” they revealed in their research (the phrase is Foucault’s) without doing the real historian’s dirty work of analysis and interpretation (the accusation is Carlo Ginzburg’s), Farge and Foucault in Disorderly Families allow the Bastille letters to, as Luxon writes, “participate in the staging of representations of suffering” rather than just being “simple storytelling,” bringing to life “the transitional moment between absolutist and administrative modes of power, the irruptions of domestic life into the social, . . . [and attesting] to the movements that veer back and forth between order and disorder — movements that Farge will later argue characterize the very discipline of history.”

What can be done with these stories — that is, the analysis and interpretation that the initial readers of Disorderly Families, and Ginzburg, wanted and didn’t get from Foucault — still, over thirty years after their first appearance in print, largely remains to be seen. Given the resurgence of interest in not only the dirty work of archival research, but in its “sentimental” and even sublime elements (doubtlessly spurred by the recent publications of Farge’s own work), perhaps this little-known volume now added to the English-speaking Foucauldian’s reading list will be mobilized in a way it wasn’t all those years ago. Farge writes in The Allure of the Archives that things uncovered in the archive, whether a packet of sun-colored seeds or, we might guess, the letters transcribed, translated, and framed in Disorderly Families, can be “everything and nothing. Everything, because they can be astonishing and defy reason. Nothing, because they can be just raw traces, which on their own can draw attention only to themselves. Their story takes shape only when you ask a specific question of them, not when you first discover them, no matter how happy the discovery might have been.”

Here, perhaps, are some happy discoveries. Now, should we ask some questions?

This post may contain affiliate links.