This piece was originally published in Full Stop Quarterly: Winter 2021. Subscribe at our Patreon page to get access to this and future issues, also available for purchase here. Your support makes it possible for us to publish work like this.

“It’s not to say: ‘Ah, there you have homosexuality!’ I detest that kind of reasoning.”

Michel Foucault, “Friendship as a Way of Life”

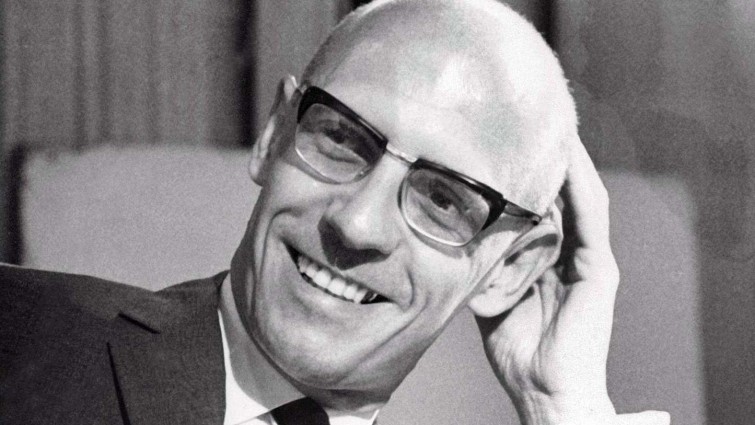

Last summer, in a series of op-eds by David Brooks and other people that I confuse for David Brooks, Michel Foucault became the object of everything that is wrong with “campus culture” and the indoctrination of impressionable undergrads into, in Brooks’s phrase, “an alienated view of the world.” Remarking on this phenomenon after Brooks’s column, Peter Coviello breaks down the way that Foucault becomes a cipher for the reactionary commentariat: “As malign incantations go, meant to summon up the dread permissive power of antifoundational speculation and Gallic attitudinizing, it will serve.” It’s still somewhat inexplicable that Foucault regularly appears as an object of debate in major anglophone newspapers. It’s not that he’s not interesting—I find his work fascinating—it’s more the way that he appears as a person: simultaneously more and less than he actually was or ever could be, detached from the methodological inquiries of The Order of Things or the theoretical and historiographic inquiry of The History of Sexuality. Instead, he becomes something else altogether, a cynosure for whatever culture war moral panic the right has most recently decided to drum up.

Perhaps Foucauldian controversies are a new annual tradition, because earlier this year yet more ink was spilled due to homophobic lies by Ronald Reagan fan Guy Sorman. While his accounts of Foucault’s pedophilia in Britain’s Sunday Times and elsewhere were shortly debunked and then retracted, the debate on Twitter continued to rage, recirculating the sources for these stories as well as the relationship between Foucault’s History of Sexuality and his various controversial statements on sexuality. After that died down, Ross Douthat joined Brooks in the New York Times to publish “How Michel Foucault Lost the Left and Won the Right.” These essays are as annoying as they are unavoidable. One need only hit refresh to see The Latest Foucault Take. This is all terribly unproductive, but the tenacity of Foucault invocations by anti-wokes and conservatives evinces the ironic way that Foucault himself, as a person, has come to stand in for any concrete historical or theoretical debate. Rather, these arguments seem to follow the form of Le Tigre’s song “What’s Yr Take On Cassavetes?” as a list of pre-selected characterizations of Foucault then determine where you stand in relation to . . . all of contemporary political debates.

These reactionary diatribes are a particularly rabid version of a more general phenomenon, of the persistent attempts to look beyond Foucault’s archive and try to find something of the living, breathing person behind it. This desire is not limited to Foucault—it’s arguably at play in most attempts at intellectual history or biography—and it has manifold uses: Left nostalgia for Foucault can be just as potent as the right’s vitriol. But this archival desire, to capture the full reality of what the historian Carolyn Steedman calls “the great, brown, slow-moving strandless river of Everything,” actually gets in the way of historical recreation because our present archives represent but a small portion of that Everything. Facing this inadequacy, the historian, biographer, pundit, researcher necessarily smooths the gaps, contradictions, and nuances in favor of the story that can actually fit in one book. This distortion is especially apparent in the case of a biography, where our own fantasies and projections stand in front of the biographical subject. Remigiusz Ryziński’s book Foucault in Warsaw, published this year by Open Letter and translated by Sean Gasper Bye, exhibits that archival desire, attempting to fill in another portion of Foucault’s biography. The book details the little less than a year that Foucault spent in Poland at the Centre for French Culture at the University of Warsaw. In mid-1959, Foucault was forced to leave Poland, in Ryziński’s account, due to a plot between the Polish police and one of the men that Foucault was sleeping with. The book joins together many of the strands that make Foucault such a potent object of fascination—his homosexuality, his intellectual work that takes up controversial subject matter, and his proximity to Europe before and after the events of 1968. Weaving different parts of the man’s life and work, Ryziński offers up an impressionistic history that is as much intellectual biography as meditation on the relationship between the author’s present and his subject’s past.

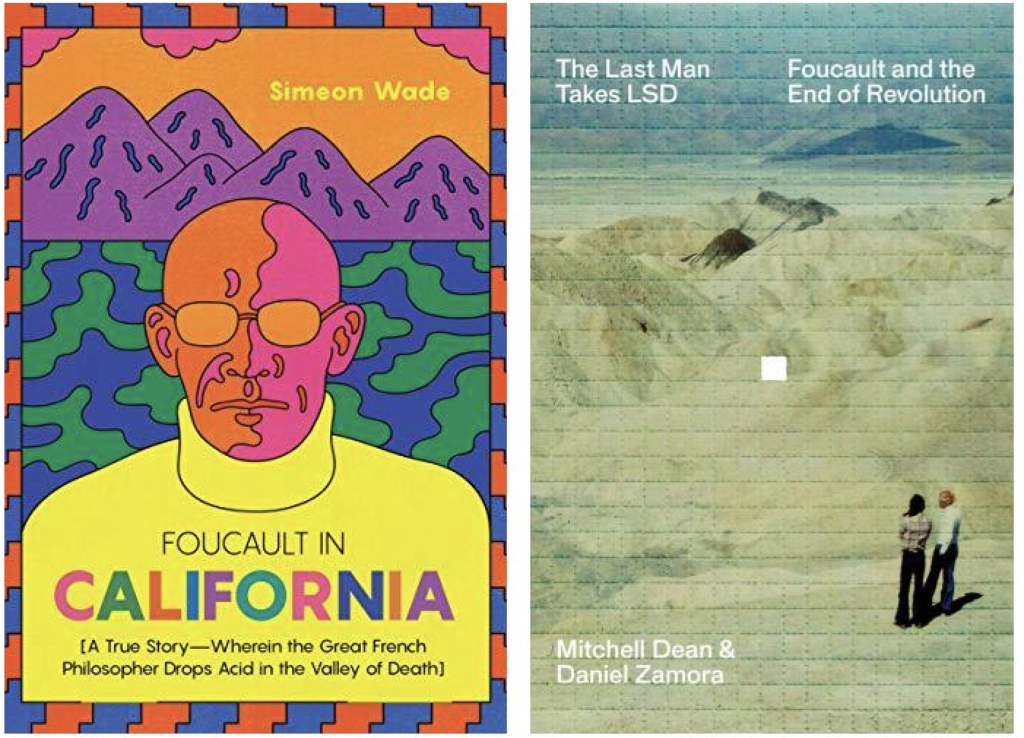

Most of the recent biographical work on Foucault has focused on his later life, research, and activism, so Ryziński’s deep inquiry into an early moment in Foucault’s career is an interesting departure, but his own approach still shares certain assumptions. Scholars have increasingly focused on specific episodes in Foucault’s life, trying to find what we might call (pace the Foucault of The Order of Things) a “biographic rift”—the moments when things suddenly changed in his life and thought. Recent books have taken up the time Foucault took LSD for the first time in a California desert, as in Simeon Wade’s Foucault in California: [A True Story—Wherein the Great French Philosopher Drops Acid in the Valley of Death] as well as, in a different register, Mitchell Dean and Daniel Zamora’s The Last Man Takes LSD: Foucault and the End of Revolution. These works vary in their treatment of Foucault and their engagement with his theoretical contribution, but they share their desire to locate that one moment when everything changed for Foucault—in this case, his acid trip in California. By Foucault’s own account, the acid trip was a transformative experience, and his work certainly shows a remarkable shift afterwards, but the persistent searching for moments of transformation runs remarkably counter to Foucault’s own practice of writing history. To take one moment from Foucault’s thought (albeit, pre-acid):

We may wish to draw a dividing-line; but any limit we set may perhaps be no more than an arbitrary division made in a constantly mobile whole. We may wish to mark off a period; but have we the right to establish symmetrical breaks at two points in time in order to give an appearance of continuity and unity to the system we place between them?

Michel Foucault, The Order of Things

This is an open question for Foucault—and a wholly discontinuous history that avoids risk of any arbitrary division would be a painful read. It’s not that things don’t change or that any attempt at marking, dividing, or periodizing is fruitless, but Foucault teaches us that these divisions and significances in turn reflect our own sense of order, unity, and discontinuity; or, put another way, what we think constitutes a life (in this case, his).

Looking to the moments we emphasize in a life teaches us about the kinds of biography that motivate our present understanding of that life. Like other recent works on his biography, Foucault in Warsaw tries to account for how a relatively short period shaped the man’s life and thought. During this time, Foucault was writing his first major work, History of Madness (originally published in an abridged version as Madness and Civilization). It remains one of the most important books of Foucault’s early career, prompting debate with intellectual heavyweights like Jacques Derrida, and his account of the way that the unspoken, outlawed, and silent is constitutive of our bodies of knowledge—of the way that “madness and non-madness, reason and unreason are confusedly implicated in each other” (“Preface to the 1961 Edition”)—ramifies throughout his thinking, in a range of topics including the history of sexuality, the formation of the sciences, and the structure of borders and territories. Whereas Foucault’s travels between eastern and western Europe, his time spent in medical archives, his political activism, and his sexual exploits all intersect with his intellectual projects in multifaceted ways, it is the last of these—Foucault’s homosexuality—that most catches Ryziński’s biographical project.

Ryziński certainly recognizes the importance of Foucault’s History of Madness. Quotations from it structure his chapters in the form of epigraphs, providing allusive power to the lyrical unfolding of his biographical account. However, just as often as he notes the intellectual influence of History of Madness, he also seeks out the book’s biographical significance for Foucault:

Without a doubt, History of Madness was Foucault’s attempt to understand himself, his otherness, which was simultaneously his true identity. It was also the gateway to his research on sexuality. Madness, after all, was a category of social exclusion in the same way as homosexuality. You need only switch the two words around.

In the book that he wrote in Warsaw, Foucault was talking about himself.

It’s hard to know what to make of passages like these. This book was certainly important to Foucault’s thought and career, and it was definitely a gateway to his monumental History of Sexuality. It’s also hard to deny that homosexuality was a form of social exclusion that Foucault experienced, nor that the Warsaw that Rynziński recovers was deeply structured by homophobia. All of this seems correct, but it’s the other turn of the screw that poses problems—that Foucault’s “otherness” was his “true identity” and that History of Madness was his self-examination of that identity.

These claims seem difficult to apply uncritically to a man who would later describe his practice of history as “writ[ing] in order to have no face” (The Archaeology of Knowledge). The first volume of Foucault’s History of Sexuality is less an attempt to situate sexuality at the core of “true” human experience but rather an account of the way that sexuality came to be constructed as one’s inner truth, across the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries by sexologists, moral reformers, and city planners. Foucault finds that the understanding of sexuality as “true identity” worked hand in hand with its role in “social exclusion” throughout that concept’s history. And what’s more, our narrow focus on sexuality-as-truth often obscures other prevalent forms of social exclusion—in Foucault’s account, sexuality was an integral tool in both the foundation of state racism and class stratification. To say that sexuality is socially constructed is also to say that it is constructed as exclusionary. Or, as Ryziński puts it in a different context, “There were no homosexuals in Poland until someone started keeping files on them.”

The irony of Foucault in Warsaw is that, while Ryziński uncovers Foucault’s time in Poland in greater detail than previous biographers, the man actually seems to be the least interesting part of the world Ryziński narrates. The book serves as something of a history of mid-century gay Warsaw: as Foucault walks through the city, Ryziński tracks the queer life that surrounds him, keeping his camera at a wide enough lens to track this broader environment—the cafes, restaurants, public parks, and grocery stores frequented by Foucault and those he knew—even if it never strays from its subject long enough to truly explore that world. As Kasia Bartoszynska points out, part of this narrow focus on Foucault—whose queer life in Poland was far from representative—derives from Ryziński’s reliance on secret police files that lack the “vibrancy and joy” that shaped so much of Poland’s queer past. Foucault was himself a historian of social exclusion, and police records and other official, homophobic documentation form an important basis for the archives of queer history. These records serve Ryziński well in his effort to uncover the details of Foucault’s expulsion from the country, but they only tell part of the story. The “vibrancy and joy” that Bartosynska describes in Poland’s queer past is not just crucial background or context to Foucault’s time in Warsaw—it is the very world-sustaining pleasure that shaped Foucault’s own life.

In this way, Foucault in Warsaw exhibits the promises and pitfalls of gay history, which must constantly navigate the way its archives are simultaneously steeped in repressive marginalization and world-making pleasure. The richness and contradiction of these histories cannot be reduced to a story merely about sexuality or about one figure. As in Ryziński’s account, these archives equally hold the lauded queers—the intellectual heroes and activists like Foucault—as well as those we’d be loath to celebrate—the traitors of the major figures of gay history, like Foucault’s lover and secret police informant, Jurek. And for every Foucault in our past, there is at least one figure like Jurek, complicated both in his sexuality and in his motives for betraying a fellow homosexual. Indeed, betrayal might actually be just as important to gay history as sodomy.

This expansive view of the more “problematic” figures like Jurek—whom the historians Huw Lemmy and Ben Miller call “Bad Gays” on their podcast of the same name—captures more of the structuring forces of our history, allowing for sexuality’s situation alongside other modes of social exclusion. This is a mode of history that Ryziński displays admirably in his late chapter “On the Trail,” which catalogues the cruising and public sex spots in Warsaw. His trail follows a remarkable cross-section of the city, through saunas and urinals, arranging the hierarchies of the people who frequented certain places as well as the fate of these places as time marched on, capitalism arrived in Poland, and more than one of these spots turned into a parking lot. “And it’s not even free!” one of Ryziński’s interlocutors remarks of one post-communist parking lot. These scenes are remarkable both for their historical evocation of a world replaced by privatized commerce as well as the people who still live to testify to their past queer vibrancy. However, his historical recreations dissolve once Ryziński returns to his biographical focus, asking, “Did Foucault come here?” In these moments, the richness of memory turns into gossip and hearsay, which can be interesting, but the focus on Foucault ironically erases the other figures who also populated those public places.

Ryziński’s book reveals a crucial tension in writing gay history. We can’t tell the story of Foucault’s life in Warsaw without narrating the wider gay world, and, perhaps, we can’t narrate that gay world without sorting out what exactly happened to Foucault there. Foucault in Warsaw begins with the problem of the archive: Ryziński knows that Foucault was in Poland and later forced to leave, but he can find no direct account of why. This is an interesting problem, and the early sections of the book are devoted to the perhaps tedious practice of trying to turn up the “right catalogue number.” And Ryziński’s own archival journey suggests that perhaps his narrow focus on Foucault’s homosexuality was the only way to tell this story. He reveals, finally, at the very end of the book’s epilogue, the search term that allowed him to find the right file to begin to write his book. That word? “Homosexuality,” of course. This revelation, then, functions as something of a rejoinder to my own Foucauldian epigraph and my desire to decenter homosexuality, putting it in relation to the other forces that shape gay history. The archive’s organization provides some evidence for homosexuality as Foucault’s “true identity.” Or at least, that’s the unifying term that lets the archive bring him together with his queer companions.

As Ryziński’s book shows, recovering these pasts requires meticulous attention to that archive, even as the archive itself is crucially shaped by the very forces of social exclusion that historians study through it. On the one hand, the archive situates (homo)sexuality as the organizing principle of this past. On the other, that categorization is itself the result of a history of marginalization. Social exclusion is not just a historical phenomenon; it also shapes the archival materials from which we study the past. It’s not as though one could ever write a history of gay life without an account of homosexual identity, but that homosexuality is still only one part of even the gayest life. A narrow emphasis on sexuality as truth, I think, ironically gives us a skewed vision of the rich history of sexuality itself. Sexuality is lived vibrantly, distinctively, and gloriously by different bodies intersected by different races and classes and genders, and even when applied to the most homonormative male figures, “homosexuality” might name their desires, loves, and intimacies, but it will always fail to fully describe them. Conversely, every biography and every history remains incomplete without accounting for the sexualities of the figures it seeks to recover from the past. Foucault, more than any other historical thinker, has taught me (and likely Ryziński) about this tension, but I worry that my own reliance on his thought as a kind of foundation for all historical inquiry risks the same pitfalls I’m trying to document here.

The final lesson of Foucault in Warsaw, then, is its demonstration of gay history’s near erotic attachment to whatever the French historian signifies, even though the next book titled “Foucault in ________” will surely yield another history that narrowly follows the man and misses much of his surrounding world. But Michel Foucault was a brilliant and influential thinker who has changed the way that many think about both history and political struggle, so it’s unsurprising that he now provokes strong feelings, whether hagiographic or vitriolic. Histories of sexuality still yield answers to urgent political questions, as evidenced by recent works like Christopher Chitty’s Sexual Hegemony and Aaron Lecklider’s Love’s Next Meeting, and Ryziński’s book deserves a place in these conversations. These recent books take up the history of sexuality to rethink the kinds of lives and desires that populated the past, detailing the intwined nature of sexuality and political struggle. Only by understanding these linked histories do we get a real view on the contradictory worlds—worlds full of both pleasure and pain, joy and betrayal—that make up the history of sexuality.

Adam Fales is a PhD candidate in English at the University of Chicago and editor of Chicago Review. His writing has appeared in Los Angeles Review of Books, Public Books, Avidly, homintern, and Hyped on Melancholy.

This post may contain affiliate links.