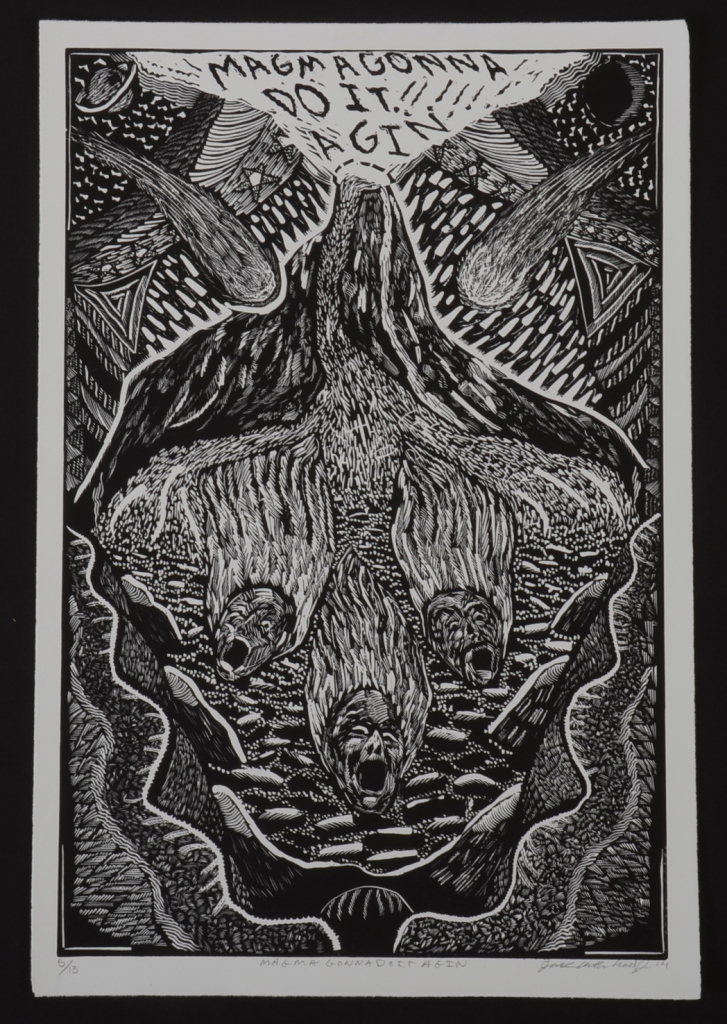

“Magma Gonna Do It Agin” by Jack Arthur Wood Jr.

In May, The New York Times published an article about a dire report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. The article laid out how the world’s poorest people, “who have had virtually nothing to do with causing global warming,” will be the most victimized by it. Besides extreme weather events that will create immediate havoc, all of the earth’s resources are at risk — water, food, land — and the continued overtaxing of these resources will lead to war, disease, famine, a whole litany of epic disasters. The world’s richest countries are beginning to make plans to adapt to the consequences of climate change, even as powerful conservative forces continue to challenge the scientific findings and derail efforts to bring greenhouse emissions under control. The world’s poorest countries, meanwhile, don’t have anywhere near the funds needed to make these adjustments.

Nowhere in the aforementioned article is there any stated hope of implementing long-term solutions to actually save our planet. It seems to take as an inevitability that humans will remain voracious consumers, that there is no other way to survive on this planet but to plunder it of all of its resources and then figure out what’s next.

* * *

I live in Austin, Texas. I live in a middle-class neighborhood and teach in a middle-class school, far enough from the coast to not have to worry about massive floods or changing coastlines. We have suffered a drought for several years, but this year we’ve had some rain — not enough, but some. The relative comfort of my life in the face of global catastrophe is a confusing reality. Perhaps that was why I found the panel’s report so disturbing. It’s completely unsurprising that the world’s poorest would reap the consequences of climate change disproportionately, and I wonder if my own political inertia comes from the fact that I’ve always known this.

Have I been operating from a place of callous disregard for masses of people? Do I consider the world’s poor some kind of collateral damage, and have all of us with the ability to delay the effects of climate change also had some collective awareness of this panel’s conclusions? I wonder if it isn’t some genocidal impulse of the ruling class that motivates them to argue against the reality of climate change and maintain the world’s dependence on non-renewable energy. Is the elite’s anti-environmentalism motivated by hope that an overpopulated earth will become dramatically empty, allowing the survivors — who are theoretically better equipped, from a social Darwinist perspective — to start a new course for humanity?

Recently I had a conversation with a friend about this idea of climate change and its genocidal implications. She made a compelling argument that individual motivations, malicious and altruistic alike, are overemphasized in the debates about climate change, because the climate crisis stems primarily from the compulsion of capitalism to continually expand, which in turn necessitates the continual exploitation of resources and labor. Individual capitalists might be greedy and ruthless, but even then they are not acting on a conscious will to destroy the environment. They might even worry about the survival of future generations, but they are powerless to intervene in the workings of the system, she suggested. I can’t say that I disagree with that. When I go into a supermarket and see excessive varieties of unsustainably sourced products, when I drive down the highway passing one fast food chain after another, when I see garbage blowing around every corner, I cannot imagine a solution within — or an exit from — this paradigm.

Maybe we are too focused on individual motivation, or lack of it, as a cause of the climate crisis. But regardless of whether people want to destroy the habitability of our planet, there is some benefit to power elites in numbing our collective awareness of the horror we are manifesting. Surely a widespread belief that some of us will survive, and the notion that the ones who survive can start anew, is not helping the situation. If the Intergovernmental Panel’s warnings about the dire consequences for the world’s poorest people are true, we are engaging in a kind of philosophical counterrevolution, undoing the modern idea that the masses matter at all. I think that is where the malice lies. That is where we all become complicit.

* * *

When I was thirteen, I was one of millions of people who watched a television movie called The Day After. This movie was about nuclear annihilation, and it was terrifying, at least to an adolescent girl who thought she had her whole life to look forward to. Three decades later, I continue to live with the fear of a potential apocalypse. Every year I’m amazed that we’re all still here. My anxiety about the future has never dissipated; it has at times been so acute that it has affected major life decisions, leading me to wonder if I’m only half-living my life for fear that the world will simply disappear.

Unsurprisingly, I also have a fascination with post-apocalyptic narratives. I have watched almost every English-language movie about the end of the world that has come out since the 1980s. 28 Days Later and Twelve Monkeys are among my favorites, and I once spent a very satisfying winter day eating potato chips and watching a Resident Evil marathon. I’ve been more disappointed with the television shows in this genre, but in my household, it is a Sunday night ritual for several weeks at a time to huddle on the couch and watch The Walking Dead.

As much as I enjoy these narratives, I also know they are a salve, helping us accept the pain and inevitability of our extinction, without necessarily advocating for resistance or a reversal of course. This is humanity’s curse, to be able to imagine our own demise so artfully, to take a sort of pleasure in it. Now, on the heels of the Intergovernmental Panel’s report, I have a new curiosity about these narratives. However terrifying they are meant to be, do they try to convince us that we can survive and start over? If that’s the case, does this fresh start depend on a catastrophic depopulation in which we ourselves are forced to participate? The rich and powerful are almost always absent from these narratives. The stories tend to be about the fighters, those that are left in a dog-eat-dog world, where you kill or be killed, and hope to transcend your basest animal instincts.

As a reader, I came to this genre much later. About twelve years ago, I picked up a novel off my sister’s bookshelf during a summer vacation and couldn’t put it down. That novel was Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower, a book I re-read recently and found as absorbing, intense, and thought-provoking as I did during my first experience with it. This summer I also read Edan Lepucki’s California, which got an unexpected boost in the wake of the Amazon-Hachette battle over e-book prices.

In California, Edan Lepucki presents a version of a world that has been “going to shit for countless generations.” This is a world coming to the end of a gradual decline, as people continually accept an ever-worsening status quo of environmental degradation and class inequality. The novel follows a young couple, Frida and Cal, who have been surviving in an unnamed wooded area somewhere outside of California. When Frida suspects she is pregnant, she wants to leave the safety of the woods and find out what else is out there, particularly in a region vaguely referred to as The Land, which they hear about from a peddler who comes to the woods to trade with them (he likes to call himself the “last black man on earth”). The peddler tells them the people on The Land are separatists, that they don’t like or accept strangers, but Cal and Frida ignore his warnings and set out to find it.

The Land is not the only place where people still live and function as a community. There are, in fact, Communities with a capital C: high-security, planned developments for the very rich. Neither Cal nor Frida have ever seen a Community, but Frida has always been fascinated by them. Some of these Communities are more forward-thinking than others. One of them, Calabasas, “was apparently pouring money into alternative energies; it’d be the first carbon-neutral and energy-independent community in Community in California.” But Frida and Cal never had any hope previously of getting inside a Community, and the rest of the metropolitan areas in California and other parts of the country have been “rendered violent and terrifying,” by the terrorist actions of a vaguely revolutionary organization called The Group. Frida’s brother had become one of their first martyrs, killing himself and thirty-one others with a suicide bomb set off in a busy shopping mall.

It’s easy enough to see why they left California, but life in the woods has not been all that bad, and this is where my problems with this novel begin, in its persistent absence of imminent danger. Danger is almost always something that is distant, in the past or the future but never present. Danger is a theoretical abstraction in the form of The Group’s terrorist tactics. Danger is talk of pirates that rape and pillage but strangely never have to travel through the woods to get anywhere. Even their isolated existence in this wilderness, which ought to be fraught with uncertainty — starvation, bad weather, wolves, bears, bands of marauders, back-breaking work, etc. — feels more like a camping trip that’s gone on too long. Here in the woods, there is a sense of an earth that has been emptied, as in this description of one of Frida’s mornings in the woods.

She still enjoyed the walk to the creek: it was hard to be afraid this early in the day, when the world felt so new. In the woods, there were many mysteries: the cat’s cradle of trees, why some fell sideways, as if pushed, branches lodged in the bramble, and why some lost their leaves and turned black, as if dipped in shoe polish, even as the others remained perfectly healthy. The pine needles still made her think of shredded wheat, though she hadn’t had a bowl of that in almost twenty years. She loved the hushed quality of her steps along the path — Cal was religious about keeping it clear — and the sounds of the earth groaning. Even the rustling of small animals didn’t bother her. If she listened closely, she could make out all the different kinds of birdsong: the beseeching, the joyful, the forlorn.

What drives them out of the woods is not violence, or even an inability to survive. It’s simply boredom — boredom and curiosity. Not surprisingly, Frida and Cal make it to The Land and even get inside its borders to live and work among its inhabitants until their inclusion into the Community can be brought to a vote. Here again, though there might be something sinister going on, there is no real sense of danger. Frida and Cal have come at just the right time, after the pirate raids have stopped and the members have found a way to live and work together harmoniously. They also trade with the nearest Community, The Pines, and get modern convenience products from them with far-off expiration dates. The Pines is still inaccessible to ordinary people, people without money, but that is the only place in the vicinity where a replica of an old-fashioned consumerist life exists. The Pines, pardon the pun, is still something to pine for, and one day Frida will find out that life inside of it has a “start-over feeling.”

In contrast, Parable of the Sower illustrates a world in which any feeling of security is an illusion. The narrator, a black teenager named Lauren, the daughter of a Baptist minister, lives in a walled community outside of Los Angeles. Not a gated community for the rich, just a middle-class enclave where the residents have built their own wall. Inside the wall, Lauren and her family are able to survive with a degree of self-sufficiency. The community grows their own food, runs their own school, and provides their own security. Only a few of them ever go outside the wall, and only when they have to.

In small ways, society is still somewhat functional. There is still a president, “a kind of human banister,” there are still stores, which are sometimes the safest place to be on the outside because of their security, and there is still a working economy for some, with an exchange of goods and labor, but the masses of people are shut out of this economy. They are the people outside the wall, trying to get in. Lauren encounters them rarely, when she goes out with her father and some other friends and family from their compound, all of them armed. At first, what Lauren sees outside their wall is not that different from what many people around the world encounter on their streets.

Up toward the hills there were walled estates — one big house and a lot of shacky little dependencies where the servants lived. We didn’t pass anything like that today. In fact we passed a couple of neighborhoods so poor that their walls were made up of unmortared rocks, chunks of concrete, and trash. Then there were the pitiful, unwalled residential areas. A lot of the houses were trashed — burned, vandalized, infested with drunks or druggies or squatted-in by homeless families with filthy, gaunt, half-naked children. Their kids were wide awake and watching us this morning.

But as the years go by, the situation becomes more and more desperate, until one day, shortly before their wall is breached, Lauren says she has never seen “more squalor, more human remains, more feral dogs than I saw today.” There is also the rise of a new street drug that makes people want to set fires, and these fires begin to rage everywhere around them.

Lauren sees clearly how quickly the destruction is escalating, and wants to find a new way to survive. In fact, she wants a new way forward for humanity. She begins preparing for life on the outside, and writing verses in a notebook that will become the seeds of a new religion. In a moving dialogue between Lauren and her father, when he asks, “‘Do you think our world is coming to an end?’” she answers, “‘No, I think your world is coming to an end.’” Butler explores this theme throughout the book — our dogged attachment to the old habits and beliefs that helped to create this mess, even after they no longer serve any purpose. There are virtually no jobs, yet people still go out searching for them. There is virtually no government, but people still vote for a president. To Lauren, there is no truth in the religion of her father, but people still worship in his church. There is no real wealth — “Even rich countries are not doing as well as history says rich countries used to do” — yet some people, like Lauren’s brother Keith, still aspire to get rich. Lauren recognizes the folly of worshiping the very forces that destroyed them, and in her eyes, although the desperate masses present an immediate threat of violence, they are not the enemy. The enemy is the old power structure that forces people to think and behave in ways that threaten the survival of all humanity.

Of course, Lauren is right. The wall is broken eventually, their neighborhood destroyed, and most of its residents are killed. She is forced to set out with a couple of survivors and head north with just her notebook, her gun, a little cash and a survival pack. The North, they are told, still has a sustainable climate and potable water and maybe even some jobs. That too turns out to be less than they’d hoped for, but they survive, gathering some more people along the way, and Lauren seriously begins to think as far ahead as she can. She is thinking of a complete break, a literal break from the old world. She is thinking of a new religion, Earthseed, in which God is Change and humanity’s destiny is to leave earth and inhabit a new planet, “to seed ourselves farther and farther from this dying place.”

Both California and Parable of the Sower suggest a possibility of starting over, but in very different forms. In California the starting over is a return to what is deemed normal in our individualist, capitalist society. It’s a way for people to once again aspire to middle-class comforts, with a few potential disruptions but no real danger. In Parable of the Sower, starting over is more of a directive than a hope, based on the fact that humanity cannot survive without a complete ideological break. The only other choice is extinction. At the end of Parable of the Sower, the feeling of starting over is actually a distant dream, and perhaps in some ways a warning for us readers. It will require years of building a viable movement and exploiting enough scientific resources and knowledge to leave earth, years these survivors might not have.

* * *

The readership of both of these novels combined doesn’t come close to the worldwide audience of the AMC series The Walking Dead, now going into its fifth season. Based on a comic book series by Robert Kirkman and Tony Moore, the television show follows a band of Southerners, led reluctantly by former sheriff Rick Grimes, who are trying to survive a zombie apocalypse. In this version of the zombie narrative, some sort of virus or mutation has created a condition in which everyone, upon their death, comes back to an animate state, unless someone is there to put a knife through your skull before you turn. Other than that, these are pretty stock zombies — slow-moving, non-thinking, hungry for living flesh. Logically, it shouldn’t be that difficult for the living to defeat the zombies, who are incapable of military strategy, but the walking dead are relentless in their sheer numbers. The zombie hordes keep on coming.

The Internet is rife with talk of how mainstream the zombie genre has become. In the 90s, there seemed to be more variety in the ways we imagined the world to end — meteors, nukes, pandemics, aliens — but in this century, the zombie is supreme. I think it has something to do with the fact that zombies, as far as apocalyptic causes go, are the least rooted in any kind of scientific plausibility. Over the past two decades, in the same cultural and political climate that oversaw a resurgence of religious fundamentalism and a denial of environmental science, evolutionary science, or even the idea of science as a worthy human endeavor, our apocalyptic narratives have also become decidedly unscientific. The zombie narrative, part science fiction, part horror, can explore the breakdown of society with a certain dimension of unreality, reassuring when the horrors of the real world are harsh enough.

Whatever the reason for its popularity, is there a better metaphor for desperate, hungry, nameless, poverty-stricken masses than the zombie horde? In The Walking Dead, just as in The Parable of the Sower, there is no safe place, and as much as these are ordinary people who may not think of themselves as killers, kill they must if they want to survive. As in California and The Parable of the Sower, the protagonists of The Walking Dead are neither the very rich nor the very poor, although the survivors come from a range of class backgrounds, and those backgrounds come to matter very little in their present situation. Since this particular zombie epidemic awakens everyone upon their death, the rich don’t have much of an advantage over anyone else. Their walls can keep zombies in as much as they keep the hordes out.

For all its campy gore, The Walking Dead is at its best when it tackles the question of human society — what form it should take, how labor should be organized, how decisions should be made, what role leadership should play, whether reproduction is a desirable goal in a world where survival is so tentative. Not all of these questions are thoroughly or even consciously explored, but they are the seeds of conflict, and make for some nail-biting narrative tension. At times, it’s even easy to forget this is a show about zombies, so caught up are we in the human conflicts and decisions.

In the third season, Rick’s group takes over a prison after clearing it of its zombies, the prisoners and guards who have perished inside its borders. It’s a reasonable but utterly depressing place to find shelter, where their sleeping quarters are jail cells. When they come across a group of prisoners who have been trapped inside the cafeteria for months, and have no idea what has befallen the outside world, there is a harried negotiation over the stockpiled food and space inside the prison. The prisoners, without experience surviving on the outside, are forced to accept Rick’s terms. They will be confined to one wing of the prison and must give up half of the stockpile in the cafeteria. The prisoners don’t fare well. Early on, Rick kills one and locks another into a courtyard full of zombies. The others survive for a while, and even become integrated into the main group, but they aren’t really prepared for the battles raging in this new world.

Nearby, another fortified community called Woodbury has established itself under the leadership of a charming but fascistic “governor.” There is something sinister in the workings of this community, in the way it recreates a traditional suburban life that shouldn’t be possible, and indeed, the residents eventually find out that the foundation of their community is a lie, that they have been living under the leadership of a kidnapper, torturer, and petty warlord. But the conflict between the prison and Woodbury is not a straightforward battle over governing styles, world views, or even territory. There are vendettas, irrational emotions, and deep personal insecurities at play, and at the end of it, both communities are destroyed and scattered. Security, again, is an illusion. Any wall can be breached.

Like Parable of the Sower, The Walking Dead doesn’t sanitize a vision of a post-apocalyptic world. There is nothing cleansing about this zombie apocalypse. All these people know how to do is fight for their daily survival, and whenever they do try something more long-term, a new, human enemy appears. It’s a grim and terrifying narrative that is relentless in its examination of human nature. Though it lacks the realism of Parable of the Sower or the subtle politics of California, it offers a moral complexity that isn’t found in the other texts. In The Walking Dead, no one really knows the way forward. There is no certainty, no cause and effect that always results in survival. There are only choices and conflicts.

In many ways, The Walking Dead avoids the cynical individualism of California. In every storyline the concept of the group is important, with all of the difficulties and rewards of communal survival. Neither does it treat the pre-apocalyptic days with any kind of nostalgia. The disaster of Woodbury suggests the folly of pining for the old way of life, and as awful as the zombie apocalypse is, the former lives of some of these characters were also violent and hopeless. People still had their base instincts, which were sometimes kept in check in the old society and often not. Some characters find liberation in the new identities they are able to forge once the restraints of society are dismantled, but their new identity is very much tied up with the group’s survival. The Walking Dead doesn’t cry out for an ideological break as in The Parable of the Sower, but there is a sense that survival requires an engagement with hard questions about our own morality.

We don’t know what the ultimate message of The Walking Dead will be, since both the comic book series and television series are ongoing. I’m sure fans will feel cheated if there isn’t some kind of triumph at the end of the narrative. Perhaps the ones who struggled the most with their choices will be rewarded with a new start. It’s likely the zombie threat will be eliminated; whether humans are capable of building a better world in its aftermath is the real question.

* * *

So, do these narratives support the idea of a genocidal cleansing, an emptying of the earth to make way for a new beginning? Of course they all do, to varying degrees, from California at one end of the spectrum to The Walking Dead at the other. Of these three narratives, California, is probably the least dire, the least populated, and the most reassuring, but it’s also a debut novel from a young writer. In Parable of the Sower and The Walking Dead, the path to a new start is much more treacherous. It is an alternative to extinction, and not at all certain.

But are these narratives also a salve, conditioning us to accept the inevitability of an apocalypse? I don’t think so. The fact is that we are going to try to make stories out of the things that terrify us. The myriad ways in which we respond to the text makes a difference. Becoming engaged in a story about the end of the world doesn’t mean we welcome it.

The thing about these narratives is that I can look up. I can look to the reality outside my window — a reality that is both objective and subjective — and feel utter relief. Unmistakably, this world is still here. Even as it is vanishing quickly, more quickly for some than others, those post-apocalyptic scenarios are not inevitable. The earth is still populated by conscious, thinking, feeling, creative, imaginative and productive people. Millions of them are living in conditions that are already abject, but all of those lives have value. If we accept, even without voicing it, that our own survival can be bought at the expense of theirs, then our survival is an illusion, and we are truly doomed.

Chaitali Sen lives with her husband and stepson in Austin, Texas. Her stories have appeared in Colorado Review, New England Review, Juked, Kartika Review, and other journals, and reviews have appeared in Los Angeles Review of Books.

Jack Arthur Wood Jr. is a linocutter from Cincinnati, OH. He seeks new inspiration daily, rejects the postmodern dilemma, does his best to pay attention, and aspires most of all to make successful images. His website is here.

This post may contain affiliate links.