I decided to attend the opening of “Dark Paradise” after my friend declared, matter-of-factly, that “Patti Smith is as close to God as we will ever get.” Curated by Tim Goossens at the Clocktower Gallery, the collaborative exhibition features works in various media by Nancy Holt, Joan Jonas, Antony, Zipora Fried, Thiago Rocha Pitta, and Patti Smith. There are two broader themes mutually shared between all exhibited artwork: first, the melancholic loneliness of landscape, and second, the duality of heavenly elements in a hellish milieu or, conversely, the demonic details in a heavenly environment.

The latter antithesis aptly explains the show’s title, but it also summarizes what makes the artwork supreme: it is honest in its presentation of both light and darkness, good and evil. The curator successfully accentuates the coexistence of contradicting energies in sublime landscapes. Landscape is often viewed as either ominous or soothing. Joseph Wright’s Dovedale By Moonlight and Cave At Evening both serve as eidetic imagery of a predominantly threatening element in the depiction of landscape. While Hans Gude’s oeuvre — for instance, the painting Efoybroen, Nord-Wales — shares a melancholic loneliness with Wright’s work, it certainly manages to evoke a soothing feeling in the viewer.

The power of the exhibit results from a context in which the two feelings coexist. Zipora Fried’s contribution eloquently marks this ruminative symbiosis. Fried’s mixed media photographs are enriched by layers of color that essentially fictionalize their reality. The artist’s creative methodology achieves an effect that neither pure photography nor pure painting could: the portrayal of a nebulous ambiance. The viewer wonders whether she is seeing an idealized reality or the fictional paradise.

This ambivalence is also present in Thiago Rocha Pitta’s video installation, O cúmplice secreto, which stands out due to its vivid visuals and dominating proportions. The video (see below) resembles a dystopian dive into the waves of Rio De Janeiro, and each viewer can choose to either swim playfully through the projection or else drown in its trippy chaos. An abstract object looms in the foreground, never revealing its identity.

Goosens’ articulate statement clarifies: “All the works in the exhibition exclude human figures and, independent of scale, evoke feelings of an undefined presence of the past or of a world still undiscovered.” Hence, the alienation the audience ought to feel — due to the jarring absence of the human form in the exhibited art — should be counterbalanced by its awe and fear of a larger implied deity in the art. The audience might sense the liminality of an environment that is moving in a new direction. The curatorial provocation is that it may remain in transition forever, never fully becoming paradise or hell.

Liminality marks the peculiar status of confusion and disarray that defines those who find themselves in transition. A similar notion of liminality appears in Dostoevsky’s Demons. Rather than existing on the median, the novel’s quiet protagonist, Stravrogin, is either pious or evil. This duality gives the character a distinct and conscious charm, which makes the reader empathize with him even if he is not a benevolent character.

A continuous theme throughout the novel is Stravrogin’s quest to find God. Yet Stavrogin’s lack of remorse for his inappropriate actions becomes apparent briefly after he is introduced, through his kissing of a married woman. It is vital to recognize Stavrogin’s abundant charisma, which balances out and take the focus away from his numerous sinful actions, which include biting a politician’s ear and pulling an eminent man by his nose, among many others.

By encompassing demonic characteristics, yet yearning to find God, Stavrogin illustrates the possibility of attaining harmony between “good” and “evil.” Stavrogin proves that the simultaneous existence of both is viable, maybe even more pragmatic than the pursuit of a middle ground. His intentions and actions, are of an extreme nature: he is morally always an outlier, never close to a median. This extremeness gives his morally-nebulous actions an air of acceptability — when he is good he is great.

Kirillov, one of the most earnest and conscientious figures in Demons, says of Stavrogin: “If Stavrogin believes, he does not believe that he believes. And if he does not believe, he does not believe that he does not believe.” The way the reader chooses to interpret Stavrogin is similar to the agency one may feel at the exhibit: the degree to which a visitor will perceive “Dark Paradise” as a paradise depends primarily on her approach towards “Romantik” themes of natural landscapes.

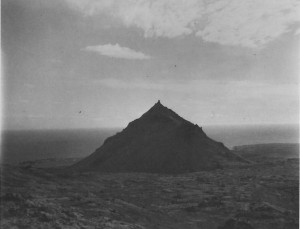

As for Patti Smith, unfortunately she was not present at the opening, allowing us to interpret her selection of photographs — some of which were taken during a 1981 trip to French Guiana, others included references to her personal influences (Rimbaud, Woolf) — without clarification of why she was intrigued by her subjects. God doesn’t have to provide explanations anyway.

This post may contain affiliate links.