There is a special place in my heart for horror films that start quietly. No zombies roaming the land in hordes, fought by terrified civilians with flamethrowers; no BANG! moments that I manage to both anticipate and fear. My favorite horror films don’t feel like horror when they begin. They begin with minuscule details, almost unconsciously apprehended, but undeniably felt. They are able to unobtrusively intensify, as dread slowly pools up from those underground lakes in your psyche, until (if you’re in the presence of a true master) you understand what is going to happen just moments before it actually does, and that awful realization falls upon you with an emotional force. Those are the stories that linger, the scenes that are hard to shake even when you walk out of the movie theater into a bright summer’s day.

There is a special place in my heart for horror films that start quietly. No zombies roaming the land in hordes, fought by terrified civilians with flamethrowers; no BANG! moments that I manage to both anticipate and fear. My favorite horror films don’t feel like horror when they begin. They begin with minuscule details, almost unconsciously apprehended, but undeniably felt. They are able to unobtrusively intensify, as dread slowly pools up from those underground lakes in your psyche, until (if you’re in the presence of a true master) you understand what is going to happen just moments before it actually does, and that awful realization falls upon you with an emotional force. Those are the stories that linger, the scenes that are hard to shake even when you walk out of the movie theater into a bright summer’s day.

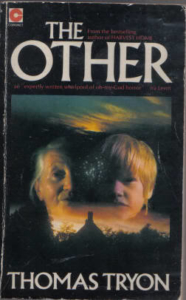

Thomas Tryon’s disquieting novel The Other is one of a small number of books that have made me feel this way — it has an undeniably Hitchcockian feel. Published in 1971 and set in a 1930s Connecticut country town, its main characters are adolescent twin brothers, Niles and Holland Perry, who are quite different in personality and temperament but completely inseparable. They live on a farm with a wonderfully varied cast of characters: their mother Alexandra, a woman who hides from the world in an upstairs room, reading and drinking the days away; their grandmother Ada, a loving if somewhat mysterious woman who grew up in Russia and has an air of latent mysticism about her; their older sister Torrie and her husband Rider, soon to be parents themselves; and some other extended family members and household hands who play roles large and small over the course of the novel. Dark events soon begin to occur, with the brothers at the center of the maelstrom.

Tryon does a fantastic job of sustaining an air of isolation, which maintains the sense of creeping dread that pervades every page. Since most of the book is focused on Niles and Holland’s thoughts and actions, any typical small-town interactions among the few, poor residents feels weighty by virtue of their rarity. These interactions, eddies in the ocean of Niles and Holland’s interior world, move the story along, but they also provide an outside perspective on the twins and the Perry family as a whole. The typical gossip around the general store counter proves to be a veil for important details of the story. After a certain point, I found myself poring over every clipped exchange, every halted sentence, in an attempt to excavate any hidden, portentous elements I might have missed.

As it turns out, The Other was actually adapted for the screen shortly after the book was published. I find myself both wanting to see how it fares on the big screen (it’s always nice when an author gets to write the screenplay for his or her own novel) and not wanting to have the film supplant my initial reading experience. While some scenes would undoubtedly gain a visceral jolt from being filmed, I think that much of what makes the novel so effective would be hard to translate to a visual medium. Tryon constantly uses his characters’ innermost thoughts to effectively force you to inhabit their minds, their points of view, and I think that that’s really the true dreadful power of The Other. Watching these characters on screen would probably be troubling. But realizing I’d started to think like them by the end of the novel? I hadn’t been that disturbed in quite some time.

This post may contain affiliate links.