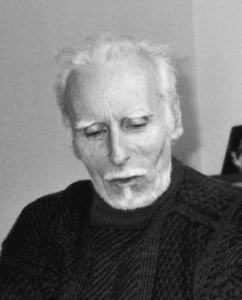

The poet Jack Gilbert passed away on November 13th, 2012 in Berkeley, California at age 87. A friend who shares my passion for Gilbert’s work notified me of his death in an email. “I’ve thought about this day before and how I would feel,” I responded. “Mainly I just feel grateful that he wrote.”

The poet Jack Gilbert passed away on November 13th, 2012 in Berkeley, California at age 87. A friend who shares my passion for Gilbert’s work notified me of his death in an email. “I’ve thought about this day before and how I would feel,” I responded. “Mainly I just feel grateful that he wrote.”

Gilbert wasn’t a particularly famous poet. He probably could have been — he won the prestigious Yale Younger Poets prize for his 1962 debut, Views of Jeopardy, and was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship two years later. But he was shy of the spotlight, a sporadic publisher at best. It didn’t help his career that he stayed quiet between 1962 and 1984, then quiet again until 1994, and then again until 2005. When he finally did publish after each long silence it was clear that he hadn’t kept apace with poetry’s turns toward the conceptual and the cunning. Instead he’d holed away by himself for decades at a time, writing poems like this one, which I find both obstinately outdated and really, really good:

Failing and Flying

Everyone forgets that Icarus also flew.

It’s the same when love comes to an end,

or the marriage fails and people say

they knew it was a mistake, that everybody

said it would never work. That she was

old enough to know better. But anything

worth doing is worth doing badly.

Like being there by that summer ocean

on the other side of the island while

love was fading out of her, the stars

burning so extravagantly those nights that

anyone could tell you they would never last.

Every morning she was asleep in my bed

like a visitation, the gentleness in her

like antelope standing in the dawn mist.

Each afternoon I watched her coming back

through the hot stony field after swimming,

the sea light behind her and the huge sky

on the other side of that. Listened to her

while we ate lunch. How can they say

the marriage failed? Like the people who

came back from Provence (when it was Provence)

and said it was pretty but the food was greasy.

I believe Icarus was not failing as he fell,

but just coming to the end of his triumph.

Gilbert was a lucid lyricist, a high modernist in his concerns, a believer in heaven on earth. His values mirrored those of the European bohemians of the early twentieth century — travel, food, sex, love, music. But his work also reveals an appreciation for routine joys, minor but evocative occurrences. His poems are punctuated by modest moments where meaning surfaces, where the heart skips and the breath catches. Take this poem, for example, about the death of his wife Michiko:

Maybe Very Happy

After she died he was seized

by a great curiosity about what

it was like for her. Not that he

doubted how much she loved him.

But he knew there must have been

some things she had not liked.

So he went to her closest friend

and asked what she complained of.

“It’s all right,” he had to keep

saying, “I really won’t mind.”

Until the friend finally gave in.

“She said sometimes you made a noise

drinking your tea if it was very hot.”

It seems contradictory that a man so hungry for experience was also at times quite austere — a recluse, an ascetic in self-imposed exile on a remote island in Greece. But perhaps this asceticism can be understood as a paradoxical manifestation of his wanting so much. He wanted all the romance and laughter and foreign cities at twilight, and he wanted all the silence and contemplation and serenity as well. He was an acquisitive man. Lucky for us, he shared his bounty.

Was he too sentimental? I have never thought so. Some have. It’s not hard to view Gilbert’s earnestness as excessive when a poem in any stylish publication is more likely to sound like a Facebook status update than Gilbert’s “The arches of her feet are like voices / of children calling in the grove of lemon trees.” But this comparison is no good anyway — we’re talking about wholly different approaches to the art form, different agendas, different stakes. His response in a Paris Review interview attends to any reservations I have about his sincerity:

“When I read the poems that matter to me, it stuns me how much the presence of the heart — in all its forms — is endlessly available there. To experience ourselves in an important way just knocks me out. It puzzles me why people have given that up for cleverness. Some of them are ingenious, more ingenious than I am, but many of them aren’t any good at being alive.”

I have a few close friends who share my love and admiration for Jack Gilbert. In conversation about him we seem to arrive at a consensus: Gilbert makes us want to be good at being alive, as he puts it.

I don’t blame the conceptualists for revising the program. From John Ashbery’s hypnagogic 1975 postmodernist pastiche “Daffy Duck in Hollywood” to contemporary Flarf works aggregated from search engine results — I like that stuff a lot. I think it’s formally innovative and intellectually exciting. But the sum of it all together impacts me less than a single verse from a Gilbert poem. “Love is not / enough,” he writes. “We die and are put into the earth forever. / We should insist while there is still time. We must / eat through the wildness of her sweet body already / in our bed to reach the body within the body.”

Even during fits of enthusiasm for experimental poetry I haven’t lost sight of Gilbert, and I doubt I ever will. His poetry demands that we live in our flesh, that we be present in ourselves. The contemporary avant-garde can be brilliantly provocative, but their work is not capable of moving me the way this poem did the first time I read it, and still does:

The Forgotten Dialect of the Heart

How astonishing it is that language can almost mean,

and frightening that it does not quite. Love, we say,

God, we say, Rome and Michiko, we write, and the words

get it all wrong. We say bread and it means according

to which nation. French has no word for home,

and we have no word for strict pleasure. A people

in northern India is dying out because their ancient

tongue has no words for endearment. I dream of lost

vocabularies that might express some of what

we no longer can. Maybe the Etruscan texts would

finally explain why the couples on their tombs

are smiling. And maybe not. When the thousands

of mysterious Sumerian tablets were translated,

they seemed to be business records. But what if they

are poems or psalms? My joy is the same as twelve

Ethiopian goats standing silent in the morning light.

O Lord, thou art slabs of salt and ingots of copper,

as grand as ripe barley lithe under the wind’s labor.

Her breasts are six white oxen loaded with bolts

of long-fibered Egyptian cotton. My love is a hundred

pitchers of honey. Shiploads of thuya are what

my body wants to say to your body. Giraffes are this

desire in the dark. Perhaps the spiral Minoan script

is not language but a map. What we feel most has

no name but amber, archers, cinnamon, horses, and birds.

Rest in peace, Jack Gilbert, and thank you for everything.

This post may contain affiliate links.