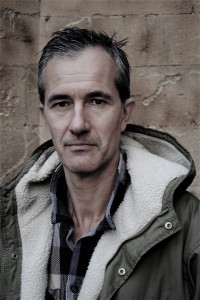

The first thing you do when you introduce Geoff Dyer is restate, eyes agog and admiring, the scope of his work: 15 books on a wide range of topics — from jazz, to the First World War, to photography, to D. H. Lawrence — plus numerous uncollected essays, forwards, and graffitis. The second thing you do is note that these works include much lauded works of both fiction and nonfiction, but increasingly exhibit the delirious hybrid of the two that have made Dyer one of our contemporary master stylists.

The first thing you do when you introduce Geoff Dyer is restate, eyes agog and admiring, the scope of his work: 15 books on a wide range of topics — from jazz, to the First World War, to photography, to D. H. Lawrence — plus numerous uncollected essays, forwards, and graffitis. The second thing you do is note that these works include much lauded works of both fiction and nonfiction, but increasingly exhibit the delirious hybrid of the two that have made Dyer one of our contemporary master stylists.

Maybe the third thing you do is mention awards, or how British he is (something Dyer himself has admitted). All of these points are valid and, in a way, deserve to be repeated. Dyer is an impressive writer with a extensive, expansive body of work, but to my mind it’s important to note how warm and inviting his writing can be. Take for example his latest book Zona, a nearly shot-by-shot description of Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1979 masterpiece Stalker.

The film, which relatively few people (Dyer’s editor included) have seen has long been an art-house treasure and cinematic litmus test. It follows a three-man expedition into a mysterious, irradiated area of wilderness referred to as the Zone. The expedition is in search of an even smaller, more mysterious area at its center, referred to as the Room, which is rumored to grant those who enter it their deepest desire. It’s a long, slow movie and nothing much happens. Dyer’s book, on the other hand, cartwheels through the bombed out landscape. Constantly digressing and deviating from what appears to be the task at hand (describing a dolly shot, or avoiding describing a character’s decision to put on a crown of thorns), it makes for an incredibly engaging experiment in nonfiction, analysis, and art.

I spoke with Dyer a few hours before he hosted Tarkovsky Interruptus, a smartly-pedigreed panel discussion and screening of Stalker put on by The New York Institute for the Humanities at NYU. In person, as in his writing, Dyer exudes the conspiratorial charm and intelligence of a good drinking buddy (rather than, say, a saboteur). Dyer and I discussed cinephilia, abandoned train stations, Where Eagles Dare, and “all that Tarkovsky bollocks.”

Jesse Montgomery: I loved Zona, first of all, and had a really good time reading it. As a critic, is it easy for you to write about something that you love?

Geoff Dyer: It depends on the thing. Personally, I find it easy to write about film and photography, and music now just about impossible, irrespective of how much I love it. And the reasons for that aren’t hard to grasp: with pictures and film you just say what you’re seeing, and in the case of this film, I just followed them along. Music, of course, is really difficult because there’s that whole thing of the technical language of music which is probably, for musicians, what it’s all about, you know? Their world is a musical world, so you’ve got that inherent problem of it being a different — not just a different language, but a whole conceptual system, really . . . Obviously I did write about music once, a long time ago [Ed. note: Dyer’s But Beautiful: A Book About Jazz was published in 1991] but . . . them days are gone!

Although, recently, I’ve been starting to think about some scenes I would like to have written about Albert Ayler. I think that But Beautiful book would have been improved if I had ended it with Albert Ayler. I always think of his death, when he’s found floating in the East River. That seems to have a symbolic value as well.

And I’ve just started to think about writing something about the Ornette Coleman quartet. . . . I can’t remember where Ed Blackwell was from but, you know, Ornette from Fort Worth, Don Cherry from Oklahoma City, Charlie Haden from Iowa: here’s this whole interesting Southwest thing going on. And then you have Charlie Haden, who is this chubby white boy playing with these three, super avant-garde black cats. It’s something I find myself coming back to at the moment.

Does that seem like another potential project that will disrupt a project you’re actually getting paid to work on?

It does help me write if I’ve got something else on my mind. As I’ve said before, I like to feel like I’m bunking off. But certainly it’s always good to have something over the horizon to get towards, to get to do, because that’s an incentive to get the thing you’re currently doing finished. Otherwise, if you’ve got the rest of eternity to do it, there’s no great urgency.

I think Zona has that sense of urgency. You talk about how you were supposed to write a book about tennis, but you wrote this book about Stalker instead. I felt drawn in by the fact that the book felt pressing, in a way.

It was a funny version of pressing, in that there was a 30-year lag between my seeing the film and writing a book about it, but I always have a very sharp sense that there are particular windows for books and this was the moment to write that one. Unfortunately, this was just after the window for the tennis book had ceased to be a window and I realized I’d left it just fractionally too late. I reckon I could have written the tennis book when I was writing the Jeff in Venice novel, and now the tennis book is just . . . Do you know that great George Steiner book called My Unwritten Books, where he lists these books that he could have written — or would have written — if things had gone differently? I’ve got to the age now where I’m starting to get a sense of the books that aren’t going to get written, because I missed the boat in whatever way.

I just saw a list of film titles Stanley Kubrick kept that are totally insane —

Just the titles?

Just the titles. Evidently he had this list that he kept fairly meticulously, with no indication of what they would be about, and there all ludicrous. There are like, semicolons in them and they’re three lines long. They’re like Guided By Voices albums. [Ed note: I seem to have made up most of the qualiative details regarding K’s list of film titles. There are no semicolons, and they’re not that long. They still sound like GBV album titles though.]

How many books have semicolons in the title?

It seems like the big question you ask yourself in Zona is whether an exercise like this — commentary on a work of art — itself becomes art. Did you reach any conclusions?

I suppose I should sort of say this off the record, but yeah, I’m 100% certain that it did become a work of art, and in truth it was always going to be. There are various ways of testing that. One is that the work has to attain a great degree of independence, whereby you can read it even if you’ve not seen the film, which is sort of an extraordinary thing to manage when it seems so closely tied to a particular thing. I think you’d enjoy the book more if you know the film, but it’s not essential to have seen it. Hopefully the film has been sort of dissolved into the book, in the same way that the script of a film ends up dissolving into a film if it’s any good. The worst kind of films are the ones where it’s a straightforward transcription of the script onto celluloid.

Yeah, that’s what Truffaut and Godard were always bitching about.

I didn’t realize that.

In the Cahiers, they wrote about it a lot.

I hate that. Sometimes you can almost see the clapper board between bits.

I’d seen Solaris and The Mirror before, but I watched Stalker in preparation for reading the book. I’d love to talk to someone who read the book and hadn’t seen the film.

You’re obviously not going to do this, because he’s not a disinterested witness, but you could talk to my British publisher. He hadn’t still hasn’t seen the film. But they accepted the book in spite of that. I think he actually said he can’t bear the thought of seeing the film, he’s so sick of the book!

While I was reading Zona and watching Stalker I was also finishing Absalom, Absalom! and there was this really funny moment — I mean, it’s pretty perfect, and in keeping with how you write in Zona about Stalker being invasive and influencing your thoughts — there was this moment when I realised that the charecters in the book are really just imagining someone else’s experience. They’re sort of narrating and commenting on history, and what they think happened, but they don’t really know. And it’s still this incredibly moving thing. There was this moment where I thought, Ah, that’s commentary, but it’s enclosed and fictive. Do you think it’s harder for people to accept nonfiction commentary as art, as opposed to this self-contained literary frame?

I think the basic thing is this idea that nonfiction is defined by its aboutness. We want it to be about whatever it is, but I like the idea of nonfiction that isn’t defined by its aboutness. Yeah, it is of course occasioned by something, but hopefully it can — I was going to say float free of that, but I realize that’s not quite right, and I’m in danger of repeating an earlier point and saying that it’s got to attain some sort of independence. We’re used to that, in a way — we’re very used to reading poems occasioned by other works of art, where [the poem] doubles as commentary and becomes this ekphrastic thing in its own right. I’ve got a feeling that that wasn’t quite an answer to your question . . .

Have you thought about subjecting any other movies to this exercise?

You know, if I wasn’t cursed by — oh god, now I’m going to do my Miles Davis impersonation: “I have to change, it’s like a curse.” I would be quite happy to keep doing this for a while, summarizing films. Particularly, I reckon, I would have a really good time doing it with Where Eagles Dare. I kind of like the idea of that, because by doing it with these two films — they’re kind of like the opposite end of the spectrum. I really don’t see how you can love film and not think that Where Eagles Dare is some kind of masterpiece. I’ve seen it so many times on telly — it’s always being shown on TV at some hour — and, you know, you’re getting drunk and you think, Oh, I’ll watch a bit of this, and then you just get locked into it, again and again.

I would really like to do that, actually, but I figure I would just get so slaughtered. It would be like in Stalker, when Writer was saying maybe he was finished as a writer, “And here is the proof!” Yeah, he is, no stars. So, unfortunately, I feel like I’d have to leave that for a few more books, at which point the Where Eagles Dare, Schloss Adler window may have slammed shut.

I think you might tap into a whole new market though — a whole new readership of dads. My dad would love it if you could do Ice Station Zebra and Where Eagles Dare!

He’s some sort of Alistair MacLean nut, is he?

I just remember those being some of his recommendations. Images from Ice Station Zebra are burned into my brain from watching it a lot as a kid. All that snow.

Yeah, it’s incredible. It looks beautiful, doesn’t it? And that cable car sequence is amazing! And then it’s got this thing: in amidst all the action, it’s got Richard Burton’s voice. I just love the way he spends all his time treating Clint Eastwood like his bitch, “Do this, do that, pick that up.” And then it’s got Clint Eastwood — who I really find an incredible bore most of the time — just moving through it with what Richard Burton has called that “dynamic lethargy” of his. Yeah . . . actually, I’m gonna do it!

So much of what I loved about Zona was your writing about being a cinephile and getting to see all that New Hollywood, ’70s stuff on film in theaters. I watched Stalker on some Romanian YouTube equivalent that would buffer in five minute chunks, which effectively made it even longer!

But you know why you did that? Because you’re young!

And because I have to come all the way to New York to see it in 35mm.

Yeah, this is — well, actually, you’re not going to this afternoon.

Oh no!

We’re going to talk about this at the event. Ren Weschler, who is one life’s great exaggerators, told me yesterday that there is not a print available in North America.

Seriously?

There was a sighting of one last seen in Connecticut, or something, and [it] hasn’t been seen in years. So we’re just going to be showing it from some pirated DVD that he bought on Canal Street!

Well, I’m sure it’ll be better than Romanian YouTube. That was a struggle.

Yeah, as I say in the book, this was a film that has to be seen properly projected, and that seems to me to be part of what it’s about. It’s about the wonder of cinematic space, and time is manifest in that, blah, blah, blah. You know — all that Tarkovsky bollocks!

I wanted to ask about your idea of heaven, that you write about in the book, where you get to watch a film revealing the location of everything you’ve lost or misplaced during your life. Is that something been thinking about for years, or did it come to you while writing this book?

It was just some gag someone told me, and it’s a great idea. Have you read that David Eagleman book Sum: Forty Tales From the Afterlives?

No.

Genius. It’s a total genius, great book, where he sketches these scenarios of what happens to you after you’ve died. And I like the way that that’s a sort of sub-Eagleman sort of thing. There’s another little homage to Eagleman in the book, that bit where I say, “What if you go to the Zone and you come back and you’re convinced it hasn’t worked and then it turns out it has worked, because your deepest wish is to be a pissed off person anyway.” His book is full of all sorts of great little parables like that.

I’ve forgotten what the question was, again . . . Oh, heaven! I’m such a Nietzsche nut, and I love the idea of philosophy. Most of it I can’t read, because I haven’t got that academic training, but so often it seems to me a good joke is a great philosophical idea in extreme miniature, and that’s why we laugh, partly because ‘wow, that boiled it down!’ So when Nietzsche says “Ah, suicide! The thought of it has gotten me through many a bad night,” you go, Oh yeah, that’s a great joke.

It’s funny, I was walking around a few months ago and I had this similar thought about heaven, where I was like: what if, right after you die, you get to see a rundown of everything you saw during your life that you didn’t know was actually a secret code and you get to see it decoded? If Saint Peter was like, “Oh, those chalk numbers you saw on that wall in ’04 . . .”

Ohhh yeah, you could get a big movie deal if you did a script of that. A Christopher Nolan project.

Maybe an Eddie Murphy project.

You did an event with John Jeremiah Sullivan last night. I read a piece on him recently, and in it he said he was growing tired of this narrator he keeps writing, but unfortunately it’s him. It’s his voice, and he wants to change! That’s a pretty dark realization. When I read that, I was wondering if, since you seem to have developed this very distinctive voice, does it ever wear on you? Is it burdensome?

It’s not so much the voice that’s the problem. The voice tends to stay the same for people, it gets to be a problem when you’re just doing the same thing with it, over and over again. My wife is very sort of cynical about it. She says, “This is weird, this book. I’ve gone 30 pages and you haven’t quoted Rilke yet!” and then of course she turns the page and there is the Rilke quote. So I’ve got to watch that. Self karaoke is the destiny to fear. But it’s the fate of everyone.

Tarkovsky, even.

Yeah, exactly. Or that review I wrote of the DeLillo book, Point Omega — er, sorry, it was in that review, but Cosmopolis was deep self parody from DeLillo. It’s the fate of any great, distinctive stylist.

I really like the term “misremembering.” You say that the book is in part a collection of misrememberings. What are misremberings good for?

Inevitably, they convey a truth and contain a truth of their own. God, I don’t want to go too far down the Bergson route, but the sort of subtle adjustments you make are really quite telling. The way that you alter things to make them closer to something that is deep to you. I’ve found that oftentimes the works of art that really affect you deeply are the ones you tend to alter. You see them again and it turns out they’re not quite as you remember because, in some weird way, [they] sort of adjust themselves to the contours of your own psyche. That process is incredibly interesting. Or what’s interesting is when you then measure the amount of movement there is been between the actuality and your memory of it, and then quite often you can work out why that’s occurred.

I do this in the book, in that digression where I write about how maybe the reason Stalker meant so much to me is because of childhood visits to an abandoned railway station. I talk about that particular station — the Cheltenham station — but the truth is, in the England I grew up in, there were loads of places like that. The term that we use in England now for these areas is “edgelands.” But there was just loads of that around. And then there was another period like that, when the whole country went belly-up and started deindustrializing. And now . . . all those places I remember from my childhood are just housing estates. And London, where there were these Zone-y warehouses, they’ve all become start-ups and stuff. Although now that the economy is truly tanking, who knows, maybe the newly developed sites might fall into a new ruination. So yeah, psychically I think I was predisposed to be ready to see that kind of landscape represented.

Well, Philadelphia is just down the road if you need a trip back in time. Plenty of that stuff down there.

Oh really? In Philadelphia? Not quite Detroit though, right? That’s where everyone goes for ruin porn, don’t they?

Yeah, that’s the hot spot. Philly’s got a fair amount of it though — pockets of it, really, all throughout. It’s a funny city.

It’s sort of a stupid film in some ways, but I always remember the opening sequence of Philadelphia with the Bruce Springsteen track “Streets of Philadelphia.” Just one of Spingsteen’s best ever songs.

Yeah, it’s a beautiful city in a lot of ways. I recently went walking on the Reading Viaduct in Philly. It’s this abandoned elevated rail line, sort of like the High Line before they developed it. It’s real Zone-y; weeds everywhere, trees growing through the tracks, an abandoned train station. It was one of those moments where you can sort of see the historical layers a city has. It’s like, I’m walking on this foreclosed-upon railway track, through the middle of the city. This is the past, I’m standing in the past. Nobody uses this anymore. And it’s also funny because you assume that in 20 years it’ll look nice again when someone redevelops it and turns it into a park. But you’re there in this strange middle stage.

Great, so it hasn’t yet been redeveloped?

No, there’s been talk about it.

I hope I go there at some point. And are you allowed to walk along it?

No.

Ah, so it’s this great outlaw kind of activity. Do you know the Joel Sternfeld pictures of the High Line before it was developed? It’s a great book, Walking the High Line. He was very instrumental, I think, in developing the High Line, which of course is one of the great successes. Everybody loves it — we tourists, New Yorkers, it’s just great. But even better if you could have had access to it when it was this Zone-y place.

This post may contain affiliate links.