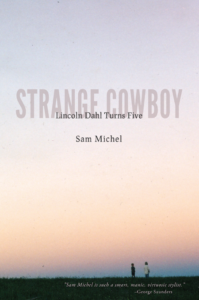

Unpublished until now, Strange Cowboy was the first novel ever written by Sam Michel, author of 2007’s Big Dogs and Flyboys and, over twenty years ago, the seminal short story collection Under the Light. Michel is married to another innovative author, Noy Holland, and like her, he was taught and initially edited by Gordon Lish. As with many students of Lish, the influence of Michel’s mentor looms large over his prose: every sentence in Strange Cowboy seems to summon up a new world, tied inside a taut knot of surging, swerving syntax. But beneath Lish’s stylistic stamp on this book, one can also discern other voices, more European in origin: Proust’s temporal consciousness; the humanist pathos of Joyce; certainly the obsessive discursiveness of Beckett and Bernhard. And Strange Cowboy’s story transposes all this into what could be called the true topos of modernism — after all, artistic truths are allowed to be counterintuitive — the American West.

In Winnemucca, Nevada, we meet Lincoln Dahl, a faltering first-time father. Like Beckett’s Murphy, Dahl sits philosophising in his favourite chair, transfixed yet transcendent, “unweighted, ecstatic.” But his introspection has left him in flight from life, or at least from his wife, his mother, and especially his son. To them he is merely “mothy, paunched, an ineffectual reminiscer.” Dahl’s son shares his name, as did his dead father, so Dahl is “the middlemost Lincoln,” the last male link in the chain of memories that makes his family a family. As such he is duty-bound to become a “model” for Lincoln Jr. His son is a “wheezy, stump-tongued, club-footed creature,” nonetheless not unwanted so much as unknown — the child of a parent nonplussed by children. “Deep, deep inside of you,” declares Dahl’s wife, “way down in your subbest-conscience, I believe you love him.” But love can’t be brought to life if it is buried too deep to disclose. For this reason, little Lincoln’s early years have been swept up in “a woozy spiral of neglect and woundings.” Today he turns five, and amid preparations for his party, his mother presses her put-upon husband to tell the story of his own fifth birthday; to relate the reconciling wisdom that “my name, too, was Lincoln . . . that I, too, was coming up on five once.”

“Why should a husband not know what to do?” wonders Dahl. “What could be simpler than to tell a son a story?” And can such a story truly convey a father’s tenderness, until now unacknowledged, untold? From such questions, Strange Cowboy weaves a lifetime’s worth of love and grief, memory and forgetting. Lincoln the elder lingers in his seat for nearly the length of the novel, dreaming of his speech, and in so doing deferring it. Recalling the ruminations of Bernhard’s narrators, his inner monologue telescopes out toward the act it anticipates: time slows down during its refraction through consciousness. As he admits, “tell me a straight line is the shortest way between two points . . . and I will argue for the scenic route from Happy Hour to Homestead.” Casting his mind back to his fifth birthday, Lincoln sets off in search of lost time. But he soon seems as likely to lose himself in time as he is to find it. For him there is “always too much to remember,” and thus “the past grows as wide for me as any future; I proceed with no more certitude in recollection than in prediction.”

Like the language in which Michel renders it, memory is a dense medium — “the warp through which experience is leavened into weight.” In this respect, to remember too much is to risk forgetting oneself; as Lincoln’s mother warns him, it is “dangerous to turn the gaze inward.” Ever the armchair Descartes, Dahl is the “doubter at the center” of his uncertain reminiscences, “turning through a shrinking future and a growing past and wondering where what went.” In this, his inner life is like any of ours: we’re all Lincoln Dahl, whenever we’re left defeated, dumbfounded, unsure of how we wound up where we are, who we are. If we’re regretful, irresolute, living excessively inside ourselves, reflection too easily leads to oblivion. In such circumstances, like Lincoln we will be bewildered by

squanderings, bygone glimpses into what I meant and did not say, what I said and wished I meant that I were saying, what I felt and could not find it in myself to say that I was feeling.

But is there a means for memory to emerge from this mist, for an act of remembrance to transport Dahl through doubt to faith? If so, might he finally say what he feels and mean it? It takes the death of his son’s beloved dog to drag Lincoln from his living room, first to the vet’s, then, in a failed bid to find a replacement, to the derelict spot where a dog pound once was. These days the places that populate Lincoln’s memory no longer refer to reality: “lamentably, the pound was not a pound,” nor can anything lost to the past be properly found. Perhaps, then, the point is not to retreat into memory, but to relate it to the future. Surfacing from his thoughts, Dahl stares at his son: a sad, silent boy, mourning a lost friend, framed by falling snow. Suddenly, somehow, for the first time, Lincoln looks at Lincoln and sees himself.

Read as a road trip, Strange Cowboy’s circular journey mimics this movement toward reconnection and recognition. Dahl drives his child to the hospice where his mother lies dying. He collects her, and takes the two of them home with him. Somewhere on the way, he at last starts his story, detailing “a day that was for me the first remembered time through which I could sustain myself,” in the hope that it might help sustain his son too. His subsequent homecoming, like Bloom’s in Ulysses, marks the end of a modest odyssey — one with a subtly self-transformative outcome:

Sure I fetched no living dog, had not managed even to provide a place in which to rest the dead one. Were I my wife, I would see my husband had departed, crossed his distance, and delivered back the same dead dog, a mute son and a husband’s mother. Yet here I found another mother, something other than a muted son, here I sounded different to myself, at least. I listened. I was a different kind of quiet . . . I must be the difference.

What Lincoln has learned is that his son has a soul like his own. And by telling his story, he has turned five again too, alongside his child, talking his way away from himself and toward the world he had hidden from; “back to tomorrow,” and to “a simpler, unconflicted saying.” No longer “meat-pulp in an easy chair, a dreamless self-deceiver,” he later tells his sleeping son and mother that he loves them. “From here on out,” he decides, “I will dedicate myself to words and deeds of restoration.” A lesser Lincoln Dahl might have lived and died without having said what he felt, his mind like so many of ours, “a mailsack stuffed with unsent letters.” So for anyone trying and failing to match up meaning and feeling and speaking, Strange Cowboy’s tale will ring true. As alive as the West’s wide skies and wildflowers, this is a story to see us through the struggle to tell those we love that we love them.

This post may contain affiliate links.