Sister Golden Calf – Colleen Burner

One of the greatest joys of Burner’s novella is that classic feature of the road trip: not having any clue who or what you are going to run into next.

Where Furnaces Burn – Joel Lane

Lane seems to be claiming that there’s something fatally false about the industrial landscape, which appears natural but in fact is inimical to life. He warns, too, against worshipping machines that comfort us even as they kill.

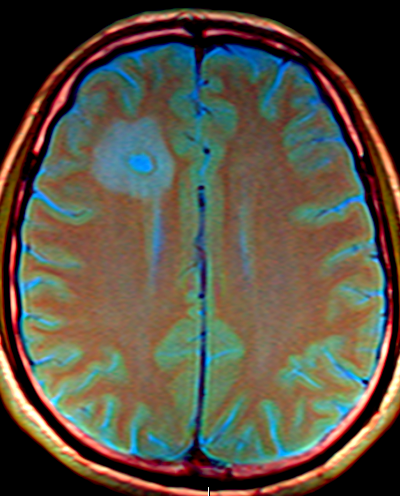

If our eyes let external horrors enter us, our jaws reverse the equation.

Little Bird – Claudia Ulloa Donoso

Reading LITTLE BIRD is a bit like reading a dream journal by someone who took her dream journal very seriously: someone who never got bored or cynical, someone who remained committed to communicating with her subconscious, someone in love with what language can do to reality.

Mind Melding Across the Genre Divide

To choose the “we” narrator is inherently political. The collectively narrated novel is fairly new—to literary realism, anyway.

Imaginary Museums – Nicolette Polek

Polek allows her characters — and therefore herself — to face the fear of futility that lurks everywhere in her exhibits. But there is a real grace in this devastation, too. Alongside the grace, stories like these provide that fizzy tincture of strangeness and humanity that every reader I know lives for.

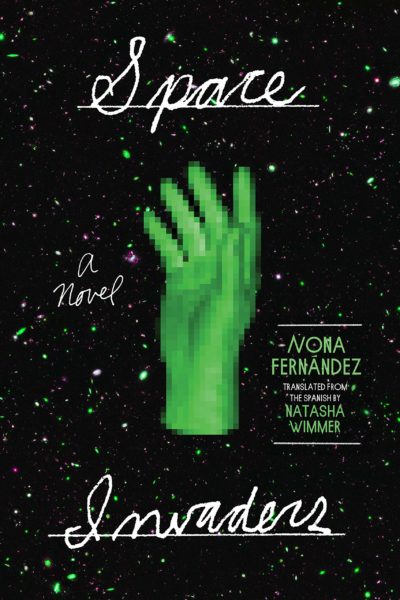

Space Invaders – Nona Fernández

Fernández does something vitally important here, something rare in American narratives of collective protest: she does not equate uncertainty with foolishness.