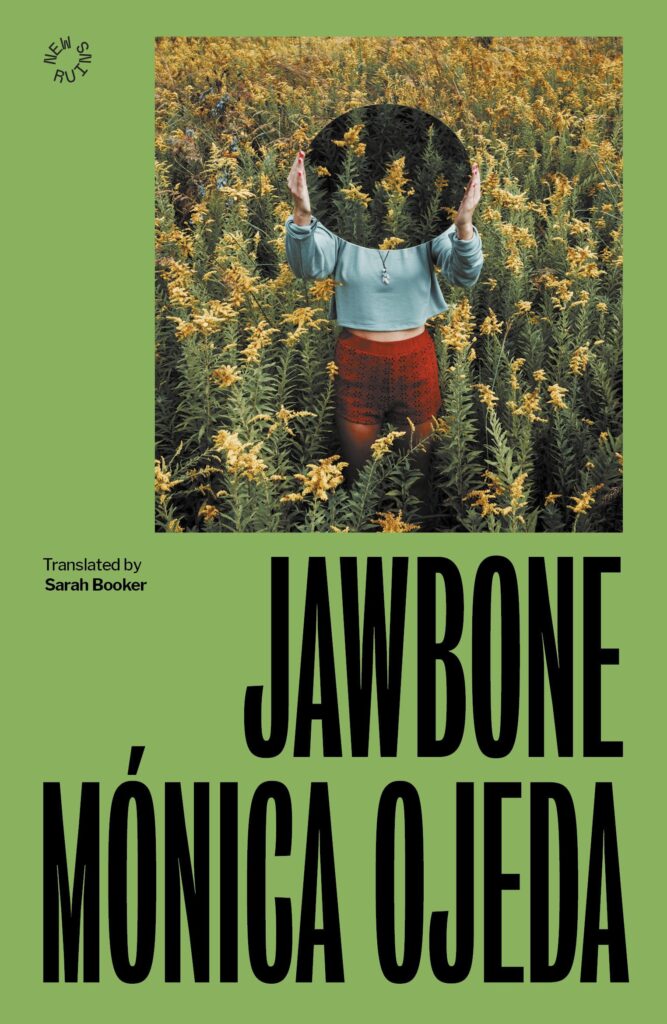

[New Ruins Press; 2022]

Tr. from the Spanish by Sarah Booker

Carol Clover, the medievalist and American film theorist who first named the Final Girls of horror, also wrote about the genre’s obsession with eyes. In her essay “The Eye of Horror,” Clover notes that eyes appear everywhere in scary movies. They show up in film posters and opening scenes, in dialogue and close-ups, in abstract forms and in soft, vulnerable physicality. “Horror privileges eyes,” Clover says, “because, more crucially than any other kind of cinema, it is about eyes.” She notes that acts of looking are typically how a sensation of horror enters a character (and us): gazing up at a monster or down at a corpse. The looking is frequently semi-passive, an avenue of transmission we can’t perfectly control.

Mónica Ojeda’s Jawbone asks us to meditate on a different anatomy of horror. The novel is Ojeda’s third, but the first to be translated into English. In 2017, Ojeda was lauded as one of the Bogotá39, the most promising young writers working in Latin America today, and just this year, Sarah Booker’s virtuosic translation of Jawbone was longlisted for the National Book Award for Translated Literature. The novel’s new argument is this: If our eyes let external horrors enter us, our jaws reverse the equation. Jawbone is about inner needs tearing into the world outside, becoming objects of horror in the process. Ojeda surrounds her readers with reminders of their hidden teeth.

In Ecuador, a teenaged girl named Fernanda wakes up to find herself kidnapped. As she becomes more conscious of her situation, Fernanda realizes that the kidnapper is her English teacher, Miss Clara. Miss Clara, a terrifying figure from the first, notices that Fernanda is awake and tells her that the two of them will discuss what Fernanda did to deserve her fate.

Through a series of flashbacks, we learn about Fernanda’s best friend Annelise, and their clique at a religious high school for well-to-do girls. Brilliant and mischievous, their friend group is particularly adept at finding ways to torture their teachers. Outside school, the girls anoint an abandoned building as their hangout. At first, the friends are content to explore the abandoned building and do the same things they would anywhere else. They chase pigeons and listen to Annelise’s half-joking sermons about her “God”— a drag queen deity she’s invented. But Annelise and Fernanda push the group further.

The building encouraged the disembowelment of a revelation beating within them. ‘Here, we have to be other people. I mean, the people we truly are,’ Annelise explained to them . . . ‘It’s not about doing just anything either,’ Fernanda was saying while Annelise nodded at every one of her words. ‘We have to do something we can’t do in any other corner of this world.’

Things begin wholesomely enough. The girls experiment with self-expression through murals and talking to themselves nonstop. They paint one of the abandoned rooms white and gather there to tell horror stories based on creepypastas—urban legend-inspired stories that circulate online. This last ritual develops more staying power than the rest, and soon their days in the white room come to be more important than any others. New elements of the ritual emerge organically—the girls come up with painful dares if someone tells a story that isn’t scary enough. These dares become experiments in pleasure and pain, as important as the stories themselves.

Horror has many well-known subgenres. Jawbone plays with the tropes of folk horror, which obsesses over cults and personal transformation through a dark communion with old, hidden ways. Jawbone is certainly all about communion: the communion of girls during adolescence, communion with new bodies and new sources of pleasure and pain. But the girls’ esoteric acts are not ancient at all—they’re invented in moments of inspiration. Jawbone is closer to what writer Sean Collins calls transcendental horror, “stories that climax with the protagonist entering a state of ecstatic or enlightened union with the source of the horror they’ve experienced.” Or at least, an ecstatic, creative climax is what the central characters of Jawbone seem to be aiming for, with Annelise acting as high priestess, Fernanda her most gifted disciple, and the other girls somewhat more reluctant communicants. In their religion, the only unforgivable sin is a lack of imagination.

At first, the girls’ experiments stay in the room they’ve painted white and set aside for horror stories and dares. It becomes a place of worship for an invented entity that Annelise takes to calling the White God. When the girls begin to show their “true” white room selves to the wider world, tension mounts. The best of such scenes takes place at a college party. The girls have been brought to entertain a bunch of male students and in another story, this moment would be dripping with threat: the girls’ ritual might shrink to a child’s game or, confronted with their naivety, Annelise and Fernanda might forget the weird idylls of their childhood and enter into a sexual world far more physical and dangerous than anything they had conceived in their innocence. Not so, in Jawbone.

The men bore Fernanda and Annelise with a game of “Never Have I Ever,” and Annelise convinces them to head up to the roof instead. There, Annelise invites them into a version of the white room ritual: If one of the men can manage to mirror her and Fernanda as they perform dangerous stunts, he can ask for anything in return and the girls must comply. Again, there’s a momentary dread that the girls will be forced to do something truly horrific, but it becomes clear that the men are not nearly as practiced at the stunts, or at coming up with torturous acts. The worst thing these particular college students can think of is showing naked photos. The girls, on the other hand, are in full cult-of-the-white-room ecstasy. As the stunts, which all involve running at high speeds along the edge of the roof, become more difficult, the reader’s dread settles on the men. We are re-affirmed in our understanding that the most terrifying force in play is the girls’ own fearless wants.

Jawbone’s relationship with sex is both central and difficult to figure out. There is a specter of queer self-discovery throughout, but the characters of Jawbone never relieve themselves of the staunch anti-lesbian stance into which they were raised. Annelise explores her erotic feelings toward Fernanda, and there is no question that Fernanda has feelings for Annelise. But while Fernanda’s love is comparatively simple, Annelise’s love is tied up in pain. In private, she asks Fernanda to harm her, which Fernanda does. Annelise’s White God—part deity, part theory of adolescence as horror—is the catalyst for her violent sexual awakening, but Fernanda is its instrument. The physical and emotional fallout from this exchange precipitates the final, gut-wrenching acts of the book.

Each of Ojeda’s central characters—Annelise, Fernanda, and Fernanda’s kidnapper, Miss Clara—chase forbidden love. Miss Clara’s and Annelise’s obsessions are born out of abuse. They are painful and terrifying to read. Fernanda’s forbidden love for Annelise is tragic, since under other circumstances it might have led to a healthy relationship. Together, the trio brings us forcibly to Ojeda’s central image of the jawbone. We watch as the girls-turned-women find need inside themselves, hard and hungry, and bare it to a world that can only recoil in fear.

How can such a story end? If there’s a danger in writing horror stories, it’s cruelty. If there’s a danger in reading them, it’s despair. Stories that face our darkest revelations don’t offer much to comfort their characters or readers. This is intentional: Despair in the face of darkness is a very real human experience, and its representation belongs in the world, alongside brighter visions. Very few horror stories give their heroines a victory over trauma in the form of permanent escape or transformation. Ari Aster’s Midsommar does it. Joan Lindsay’s Picnic at Hanging Rock does it, and Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle. Jawbone does not. As one of Ojeda’s characters says, “In the end, it’s about diving into the fear, not overcoming it.”

Amelia Brown is a writer living in Boston. She holds an MFA from Bennington College.

This post may contain affiliate links.