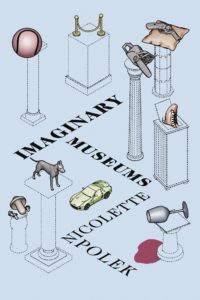

[Soft Skull Press; 2020]

Nicolette Polek is a literary archivist. Her debut short story collection, published January 14th of this year by Soft Skull Press, is called Imaginary Museums after the title of one of its twenty-six stories, but that’s also an apt description of Polek’s curation process. In an interview with The Daily Californian, Polek talked about how she pieced the collection together from her previously written stories, many of which had already been published elsewhere: “I knew I wanted to write a book of short fictions, but I didn’t know I had a collection until I started filing the stories into categories, and a precise shape appeared.”

The collection is short—114 pages—and the categories which make up its shape come in the form of four sections: “Miniature Catastrophes”, “American Interiors”, “Slovak Sceneries”, and “Library of Lost Things”. All of which have their own distinguishing themes. For example, the stories included in “Miniature Catastrophes” thematically revolve around personal failure: from societally defined ideations and potentially life-changing failures, like an abandoned wedding; to the acutely subjective, failures of fleeting personal significance, like forgetting licorice at the store. The entries in “Library of Lost Things” are the most faithful to their theme, each one presenting the story of something missing. Sometimes the whole story is a literal inventory of what’s been lost (“Girls I No Longer Know,” “Pets I No Longer Have”), and sometimes the loss makes itself known more subtly, as something partial or fragmented, and often through a tone of overwhelming nostalgia or anxiety (“Field Notes,” “Rest in Pieces”). Whereas, the interpretations of “American Interiors” and “Slovak Sceneries” are a bit broader. The stories in these sections feature characters and narrators who either visit or live in the two countries. While setting and cultural narrative is often central to these stories — “Sabbatical” (found in “Slovak Sceneries”) is a village history by way of a house tour, and the titular “Imaginary Museums” (included in “American Interiors”) follows a woman who travels to New York City to find artistic inspiration at the supposed “Air-Conditioning and Refrigeration Museum” — both sections also included stories that didn’t seem to fit any specific place-category, but instead captured the social atmosphere of unnamed but evocative locales, such as “The Nearby Place” (“American Interiors”) and “The Seamstress” (“Slovak Sceneries”).

Although some stories appear to stand alone, what binds all the sections together is the very self-awareness of their collection, the organization of minuscule pieces into something that feels like looking at a display of curios. With its exhibit-like section titles, the stories’ obsessive focus on physical objects and Polek’s literary curation process, reading this book really does feel like walking through a museum. Another reason for this, according to Polek’s publication acknowledgements, is be due to the fact that some of the stories in Imaginary Museums, such as “How to Eat Well,” and “The Nearby Place”, were on display in art galleries; and that “The Squinter’s Watch” was originally written as a press release for a gallery show. To my knowledge, there aren’t any images online of the stories in their exhibitions — the closest I could find were those of the more traditional gallery works that were shown alongside Polek’s, and images from the show that “The Squinter’s Watch” was a press release for. Still, even without these visuals, the fact that I can imagine the stories hanging instead of solely read, speaks to their unusual physicality, as well as that of Polek’s writing which, with its pristine, awe-inspiring and slightly chilly tone, evokes a similar atmosphere to that of a museum.

Threaded throughout all the stories, underneath all the curation, there is one background theme which appears again and again: a longing for the natural world. In particular, the theme is prominent in “Library of Lost Things,” which, given the section’s tone of nostalgia and loss, evokes the tragedy of humanity’s global and historical alienation from nature. It’s not that Polek is an environmentalist or a forcefully eco-conscious writer, but the choice is interesting, given that such an uncontrollable and sublime theme is somewhat antithetical to the obsessive organization of the book’s larger frame. For instance, nature features strongly in the story “Rest in Pieces,” in which a worker in a water supply company chases a pink tennis ball down an office staircase. The worker is anxious, constantly waiting for the next catastrophe to occur, and in an attempt to comfort herself, she rearranges objects. As she chases the ball, she thinks of herself as moving through the layers of a city as if they were layers of a rainforest. From this, the anxieties and catastrophes of the urban world seem superimposed upon the natural world, and as the narrator descends the staircase, she allows herself this broad perspective. But, by the end of the story, she becomes anxious again and her perspective once more shifts into that of claustrophobia. So she goes back to rearranging objects, “killing time before the next thing comes undone.”

Polek’s closing lines, like the one above, tend to be perfect — produced, framed, polished. My favorite comes at the end of Field Notes, a story which takes form as an anxious, hyper-detailed third-person examination of a woman’s failure to find the peace she seeks in nature. And then, at the end, Polek devastates with a sudden, simple line of understated irony: “By the end of the walk, a bluebird has seen Erica thirty times, but Erica never saw it.” Her characters, too, feel smooth, perhaps in the way of mannequins in a history exhibit: frozen in a very specific moment, in a way that says little about an individual as singular or whole, but plenty about a particular experience. Interiority is rare with Polek’s characters. Although when Polek’s precise arrangements of her objects and humans-turned-objects work, they work the way a spectacular diorama might; like a snapshot of quotidian life that is so perfectly framed that it becomes surreal and elevated. Nevertheless, there are times in which these narrow frames feel disappointing.

For example, one story that I feel may have benefited from expansion was “Your Shining Trapdoor.” In this, a woman visits her once-refugee parents in their American home. They’ve filled their rooms with the mismatched detritus of other people’s lives, collected over time from thrift stores and yard sales. There’s a bright red panther with a lightbulb in its head, moldy furniture, a VHS player, among other things. “Feebee’s parents’ house,” as Polek first describes, “is small and dark. It is cluttered with hanging pots of ivy, and smells like dust. Wooden statuettes cover many surfaces. Feebee wipes the cobwebs from them.” This opening is moving, filled with detail and gesture that paints a heartrending portrait of the couple and their daughter. But in the end, the daughter “wishes they could leave, could find a place for themselves where they fit.” Immediately afterward, on the last page, she makes trapdoors for her father and mother; trapdoors that lead to dream-like rooms under their actual rooms, filled with places from their hometowns: views of mountains and the park where her father once played soccer. This is a believable desire of course — a mix of freedom and nostalgia — and Polek illustrates a fantastic fulfillment of it, but it is so quickly dispatched that it feels too easy: escapist without offering the lift of true hope or the whack of true futility.

It’s hard to know what readers will make of Imaginary Museums. Despite, or maybe purposefully emphasized by, Polek’s wonderfully neat curation, the stories of this collection push against categorization. “What are these? Weird parables? Dark Dreams? Warnings about the afterlife, death, marriage?”, writes Deb Olin Unferth in her blurb for the book, which finishes with the claim that “Polek is willing to go to a disturbing place and stay there.”

I wanted the stories of Imaginary Museums to be disturbing, and some came close — occasionally surreal, and frequently sad — but I can’t say I ever felt pushed over the edge into real, itchy distress. And Polek, for all her incredible vision and powers of prose, is not, in fact, willing to stay where she goes. This isn’t a condemnation — it just doesn’t seem to be part of her project here. That’s partially due to length (the longest story is ten pages, and most are three or fewer), but mostly it’s down to those occasionally too-perfect endings. They’re not tied up neatly with a bow. But much like the daughter (“Feebee”) in “Your Shining Trapdoor,” Polek seems to want to provide a quick escape from a crushing mundane existence. And, at times, she offers a neater resolution than her characters’ situations demand.

For the most part, though, these are fantastic stories with an impressive range. The devastating ones were my favorites, those in which Polek allows her characters — and therefore herself — to face the fear of futility that lurks everywhere in her exhibits. But there is a real grace in this devastation, too. Alongside the grace, stories like these provide that fizzy tincture of strangeness and humanity that every reader I know lives for. Polek is a writer of enviable skill, and at the very beginning of her career, I leave you with this statement: get excited.

Amelia Brown is a writer living in Boston. She holds an MFA from Bennington College, and is a regular contributor to the Ploughshares blog. She is at work on her first novel.

This post may contain affiliate links.