The following is from the latest issue of the Full Stop Quarterly. You can purchase the issue here or subscribe at our Patreon page.

1. Cave Language

Ours is a lonely literature. A protagonist is almost always, first and foremost, an individual—they reach for meaning alone, and teach us to live as individuals, too. There are a few formal tools writers have on hand to break this mold. Of them, the collectively narrated novel is fairly new—to literary realism, anyway.

The “we” pronoun has been used to narrate American short fiction off and on at least since William Faulkner’s “A Rose for Emily.” I say off and on, but really, it’s mostly off. The first plural is typically relegated to the bottom of the narration barrel along with second person—left moldering until somebody weird like Steven Millhauser sees it down there and scrapes it up. And to be fair, it is quirky. Collectively voiced fiction is devilishly tricky to write, and it can be difficult to read, too. It often lacks that psychological depth that comes from singling one character out, and so denies us our little hit of voyeurism. For these reasons, “we” narrators seem to work best in the short form. There are a few writers of literary fiction, though, brave enough to spin it out for a whole novel. I’ll look at three: Justin Torres, Nona Fernández, and Julie Otsuka. These collective novels often have a few things in common and share at least one notable limitation.

Justin Torres’ We the Animals was published in 2011. Its “we” narrator is a trio of brothers, half white, half Puerto Rican, growing up together in upstate New York. Multiple forces bind its central collective, but two of them are shared joy and shared victimhood. The “we” that is made through shared joy and shared creative experience comes across most clearly when the trio plays together as young children. In their games they imitate other trios—the Chipmunks, the Stooges, the Billy Goats Gruff—and find collective identity in their joy at being three together. During this time, they all speak with the same tongue: “When we were three together, we spoke in unison. One voice for all, our cave language.” There is an all-powerful feeling that comes from this sort of unity. The boys feel this supreme power and take joy in it, saying “The magic of God is three,” and “We were the magic of God.”

Later, we come to see the unity between the trio as being just as much a product of their shared victimhood as their shared creativity. They play a game in which they smack a ball onto the street to imitate their father’s beatings. The joy in cohesiveness during these scenes is gone: “We stood to the side of the road and looked hard at the drivers through the glass as they passed,” and “We had our blue ball and our anger . . .” As one of the brothers says, “There’s white magic and there’s black magic.” Their power has taken on a destructive hue.

There is an individual at the heart of We the Animals—one of the brothers whose voice is more distinct throughout. In the end, his voice is singled out entirely as he comes of age and discovers that he is gay. He is separated from his brothers and his parents and after a traumatizing stay in a psych ward; the “we” that had dominated the book is shattered. The overwhelming feeling that Torres leaves us with is devastated isolation.

Similar in scale, Nona Fernández’s Space Invaders, published in Spanish in 2013 and translated into English in 2019, follows a tight knit group of friends as they grow up in Pinochet’s Chile. The friends meet in school and grow close, but the cord that draws their narratives together is something they lack: a lost friend. “We share dreams from afar. Or one dream, at least, embroidered in white thread on the bib of a checkered school smock: Estrella González.” Estrella’s family fled Chile suddenly, while the group was in high school. Though she’d been one of them, her voice was never a member of the collective, implying that the group has been bound more by what they are missing than by what they possess.

Fernández, too, shows both the white and black magic of the collective. She does it through the central, titular metaphor of the aliens in the game Space Invaders. Over and over, the friends of the “we” collective assume the aliens’ formation: “We form a perfect square, a kind of game board. . . . We spread out, each of us resting a right arm on the shoulder of the classmate ahead to mark the perfect distance between us.” The group finds power in this formation, and self-determination, as when they walk out of school together to protest military rule. But the formation is used against them, too: their school and their government frame them into their rank-and-file collective to domesticate and dehumanize.

Scaling up from the intimacy of Fernández and Torres, Julie Otsuka’s The Buddha in the Attic, published in 2011, is narrated by Japanese women who came to the United States as brides for Japanese workers. The “we” in this case is so large that the women who make up the collective don’t all know each other. Though Otsuka never switches to the singular, she never loses any specificity of time or place or action: “On the boat the first thing we did—before deciding who we liked and didn’t like, before telling each other which one of the islands we were from, and why we were leaving, before bothering to learn each other’s names—was compare photographs of our husbands.” Even after they leave the boat, and each other, they are united by a shared voice. The women are separated, but still the group describes everything together: disappointment with their new husbands, settling in labor camps at the edges of hostile white towns, giving birth, building young families of Japanese Americans, and, finally, being forced into concentration camps by the United States government after Roosevelt’s executive order 9066.

Otsuka makes a perspective shift at the end of her novel, though unlike Torres she stays in her pitch perfect “we.” Suddenly, the “we” we’re hearing is a collective of non-Japanese Americans. The neighbors of the families who have been detained watch the empty houses and wonder what’s happened—how so many people from their towns could have all disappeared at once without any one of them noticing, and whether it was anyone’s fault. Otsuka uses that same tactic of specificity to give voice to these erstwhile neighbors as they miss their Japanese friends and lovers and maids. They wonder if maybe they should have done something, even as they steal from the abandoned homes: “On block after block, Oriental rugs materialize beneath our feet. And on the west side of town, among the more fashionable set of young mothers who daily frequent the park, chopstick hair ornaments have suddenly become all the rage. ‘I try not to think about where they came from,’ says one mother as she rocks her baby back and forth on a bench in the shade. ‘Sometimes it’s better not to know.'” Again, Otsuka shows the dark side and the light side of collective—her dark side being that you can hide in the anonymity of it. You can lie to yourself about what you’ve seen and done.

What to make of all these collectives? Is there an underlying form to their stories that sets them apart? It’s hard to miss the consciously political tone. The political bent of the works exists to different degrees across the three novels I’ve mentioned. It’s tempting to say that the political-ness of a collective novel derives from the scale of its collective—Torres being the least conspicuously political of these three, and also the smallest unit. But that gets questionable pretty quickly—is Space Invaders somehow “less political” than The Buddha in the Attic? No, of course not.

To choose the “we” narrator is inherently political simply because, in choosing collectivity the author suggests a group’s interests, rather than an individual’s. The “we” narrator is scalable. It can be of whatever demographic or size a writer wants to explore—a particular gender, family type, ethnicity, type of worker. But in the genre of literary fiction, there is an upper limit to all of this. The limitation is that we have to group based on circles we’ve already drawn, within the political scales and definitions that already exist.

2. Galaxy Brain

Our concept of “literature” is determined and limited by our cultural imagination—so asserts Terry Eagleton in his classic Literary Theory. The genre of literary realism looms large in our current imagination. It makes up the bulk of what Americans consider literature. But as a genre, literary realism can be a bit of an obstacle when it comes to thinking our way toward new literatures, and new cultural configurations, because it focuses on the way things are. There is a genre that has historically tackled the way things could be: science fiction. Unlike literary realism, science fiction frequently invokes the collective mind—it’s one of the major tropes. But unlike in literary realism, science fiction writers are free to assemble their groups from whomever they please. They’re not bound by current politics.

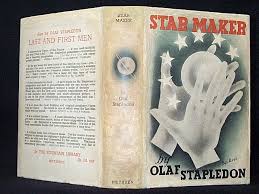

Olaf Stapledon’s Star Maker (1937) introduced the collective narrator into English language science fiction decades before any of the other novels I’ve mentioned were written. It was also popular, which might come as a surprise to anyone who reads it today—the novel can be frustrating for reasons I’ll describe later. But in its day, it attracted a star-studded crop of fans, including Borges, Virginia Woolf, Doris Lessing, and Freeman Dyson, whose famous “Dyson sphere” concept is borrowed from the later chapters of the book.

The basic plot of Star Maker is this: an English man is sitting on a hill, looking up at the stars one night when he realizes that he can throw his mind into space. From there, his disembodied perspective floats through the galaxy, zooming between star systems until he finds another planet that supports intelligent life. Discovering that he can communicate telepathically with this alien species, he inhabits the mind of one of the planet’s philosophers (they have them, too!) and learns about the species’ culture for a time before taking off again into space—bringing the philosopher’s mind along for the ride. Together, the two minds explore more star systems, and more planets with intelligent life, each one a little more alien than the last. Along the way, more minds join in the galactic tour, forming a kind of Katamari consciousness. Eventually, they realize that they can drift through time as well as space. They witness the beginning and the end of our universe and meet its creator—the titular Star Maker—before being flung home again.

Though Stapledon writes with a plural narrator, drifting often into “we”, and sometimes a collective “I,” he also gives a third person account of each world’s history—a good reminder that histories are maybe the original collective fiction. The group continuously redraws their circle to include minds from these worlds: symbiotic pairs of spider- and fish-like beings, scent-based humanoids, flocks of bird-like beings that maintain collective consciousness through radio waves. During these third person sections, Stapledon’s prose feels closer to that of an anthropological or philosophical text than a work of narrative fiction. It may be this that inspired Stapledon himself to remark about Star Maker in his preface, “Judged by the standards of the Novel, it is remarkably bad. In fact, it is no novel at all.”

I think it’s fair to say that it is a novel, really, albeit one that makes for some occasionally dry reading. But Stapledon may also have meant that his work was no novel in that the book completely eschews the traditional individualistic protagonist and arc. In fact, his collective narrator does have an arc, it’s just the widest possible one: Star Maker is the story of an entire universe’s struggle towards a utopian sharing of consciousness. Early on in their travels, the mind explorers cannot visit—or even find—worlds that are not experiencing the same “spiritual crisis” as the one we humans are undergoing on earth: “This crisis I came to regard as having two aspects. It was at once a moment in the spirit’s struggle to become capable of true community on a world-wide scale; and it was a stage in the age-long task of achieving the right, the finally appropriate, the spiritual attitude toward the universe.” Eventually, the travelers do gain the ability to see a different “stage” of spiritual struggle, but only after watching species after species reach for true community.

As in literary fiction, the “we” narrator of Star Maker is a consciously political choice. Stapledon wasn’t coy about using his novels as vectors for his own philosophy. The last lines from Star Maker even present an honest-to-goodness, whack-you-over-the-head moral. Stapledon himself was a pacifist, and in Star Maker he seems to favor communistic organization, with an asterisk. He repeatedly draws a fine line between healthy communal life and “the cult of the herd” in which all original thought is lost. Almost all of his alien cultures strive first to overcome whatever version of pure individualism exists in their world. Then, as communal telepathy sets in, the alien societies try to find a balance between this collective existence and a demolition of individual consciousness. For Stapledon, this is the primary spiritual struggle of all intelligent life.

However utopian Stapledon’s hopes for us may be, he doesn’t gloss our chances. It’s painful to watch the alien civilizations try, and usually fail, to achieve some version of global harmony. In the end, Stapledon’s narrator is sent home to his earthly, isolated consciousness with only a fractured memory of his transcendental communal state. His limits of feeling shrink back to the mundane nuclear family. The “we,” when it returns, refers only to himself and his wife. Essentially, he’s been transformed back into a narrator of literary realism. He ponders what’s in store:

“And the future? Black with the rising storm of this world’s madness, though shot through with flashes of a new and violent hope, the hope of a sane, a reasonable, a happier world. Between our time and that future, what horror lay in store? Oppressors would not meekly give way. And we two, accustomed only to security and mildness, were fit only for a kindly world; wherein, none being tormented, none turns desperate. We were adapted only to fair weather, for the practice of the friendly but not too difficult, not heroical virtues, in a society both secure and just. Instead, we found ourselves in an age of titanic conflict, when the relentless powers of darkness and the ruthless because desperate powers of light were coming to grips for a death struggle in the world’s torn heart, when grave choices must be made in crisis after crisis, and no simple or familiar principles were adequate.”

There are moments in Star Maker—unfortunate moments—which reveal that the cosmic, truly communal mindset is beyond the grasp even of its writer. He maintains a fairly strict gender binary whenever he can, even when talking about sentient clipper ships, and heteronormativity seems to be in vogue throughout the universe. Stapledon relies heavily on what are now extremely baggage-laden words of cultural exclusion like mentally superior, primitive, perverts (though he uses that one specifically in reference to violently imperialist cultures).

Stapledon’s issue here may stem from his own cultural inexperience, but the main reason he falters is a lack of exactly the kind of detail that drives literary realism. In a chapter about halfway through, for instance, Stapledon casually and horrifyingly mentions that superior galactic societies use eugenics to miraculous ends. Now, he uses the word “eugenics” to mean any kind of genetic enhancement, and specifically a kind of genetic engineering that has surpassed earlier, cruder, genocidal forms. But his prose lacks the kind of detail that, say, Otsuka uses in Buddha in the Attic. Stapledon’s lofty remove doesn’t allow him to do the necessary work of showing us just what these genetic “improvements” looked like for individuals in society, so we can’t really judge the ethics for ourselves. Until the time comes when we have all ascended to telepathic galaxy brain, that here-and-now treatment of human experience is a must.

But where Stapledon struggled, others have soared. Le Guinn, Clarke, Banks, and others have done deep, imaginative dives on communal culture without sacrificing human detail. Most modern science fiction is realist whether describing human psychology or the level of grit in a spaceship hallway. Plenty of it is “literary,” too, in the sense of being beautifully written. This, then, is the trick: can we imagine our way out of the tired genre circles we’ve drawn for ourselves? And the bigger trick—in so doing, can we imagine our way into a truer community? Stapledon thought so, and so do I, though it’s hardly a popular position these days. Oh, and that whack-you-over-the-head moral that Star Maker ends on? It’s pretty good here, too:

“Two lights for guidance. The first, our little glowing atom of community, with all that it signifies. The second, the cold light of the stars, symbol of the hypercosmical reality, with its crystal ecstasy.”

Amelia Brown is a writer living in Boston. She holds an MFA from Bennington College, and is a regular contributor to the Ploughshares blog. She is at work on her first novel.

This post may contain affiliate links.