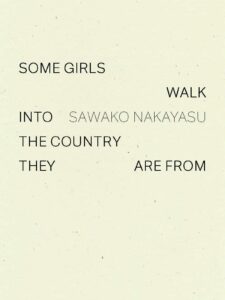

[Wave Books; 2020]

Some girls, in Some Girls Walk into the Country They Are From, are ten girls to be exact. Some are also ten in one. Some are “some” as in a few, a crew, a troop, or a dozen — or so. “Some get the stars shaken off of them,” Sawako Nakayasu writes in her opening poem. “Some are given rose-scent. Some are fed animal protein to fatten them up for the flood.” From the ceremony of “Girls Rolling Themselves,” they emerge “ten new girls, A through J” — anti/social variables tessellating across linguistic and cultural registers.

Together, throughout Nakayasu’s richly perplexing new book of experimental verse, prose, and translation, these “some girls” beckon definition but evade, with every gesture, the satisfaction of answers. Rather, they perform a dizzying diaspora at the fringes of girlhood and selfhood, probing the precarious proximity between placement and estrangement, departure and arrival. Through tongue-in-cheek revelries, “some girls” disturb the myths of origin, genre, and gender.

Some of some, it turns out, are spry, burgeoning forms, about to hatch out of the next like a nesting doll. In “Girls Inhabit Arch,” for instance:

One girl is a gift. One girl is a city. One girl is a city visiting another city not itself. One girl is sadness. One girl is a well.

The riddles are endless, the paradoxes vast beneath a surface of sing-song silliness. In them, the girls and their designations as such are overt, as if they are in their naming both suppositional and determined, both allowed and subjugated:

The hat styled with pigeon wings is not a girl . . . The girl walking nonchalantly through the streets of a European city is not a girl, unless there is a bat.

(A . . . bat?)

Others are riper with horror than humor, even “Laid Out Along the Road Like Attenuate Parts” in one translation, which appears to be as much a disassembly as an assemblage of meaning. The condition of dismemberment, and its associated pain, is shown to apply even when the act is not depicted or experienced directly by the subject in frame. Which is to say, the event of displacement is not limited to the act of being displaced.

We see iterations of this referred pain throughout the collection, with translations whose “originals” are not overtly staged as originals; whose originals might not exist — here, or anywhere — or whose originals might not be the actuals, the translations maybe serving instead as scaffoldings of negatives, as molts of imagined origins. It would be more accurate still to say there are no translations at all, only forms — and combinations of forms — of translational text.

To what extent these girls can be considered originals in themselves, moreover — or even selves — is an open question broached in translational tides. Indeed, in some ways these peculiar “some” are more like simulacrums or caricatures of personhoods than “real” girls. They are girls, yes, but they are also Girl: community, entity, and epithet (re)claimed. At best they possess the clamor of old friends, tones of the elemental, pixels of Virginia Wolf’s The Waves. At worst, though, they, and their reader along with them, can feel trapped in a Claymation nightmare.

We encounter them, whoever they are, under whatever abstract premise Nakayasu concocts next. Freeze-frames of mid-circumstance: in crisis, in the act, in suspense, in suspension, in monologue, in dialogue, in choruses both creepy and joyous; in entanglements too thick to parse out with a single comb; in the throes of abstractions too abstract to describe without unraveling into deeper abstractions. Etc. We find them floating in Jell-O, or enclosed in chip bags, or swimming in an ocean of hats, their behaviors as variable as imaginable. They may be “Under the Condition of Sending a Warm Thing by Spoon” or “Under the Condition of a Small Hole in the Floor of an Auditorium.” They may be walking into a bar, clustering around arbitrary flash points of contact, or responding collectively (and quickly!) to serial calls “From High Up.” But almost always, it seems, they are moving.

Not physically, necessarily, but still with visceral suggestion. The scene that a given poem stages might be static while the language is contrastingly in flight, as in “Girl J and Girl B Have Parallel Meals,” wherein “Girl B chews, Girl J chases. Girl B spits, Girl J interrogates, Girl B gargles, Girl J swallows.” Or else, the arrangement might be implicitly moving while the language sinks into itself, as in “Girl A’s Peanuts and Girl D’s Mouthful,” wherein “Girl A [is] on the train with peanuts. The expectant fullness of Girl D’s mouth. Growing distance of the floor.” Shot through by the vector of the train’s motion through the verbless phrases, there is a vertiginous sense, both static and running off script, that the train may be headed for a blown bridge.

The sense of the sensational is, of course, playfully subverted whenever anticipated. In “Blow Up and Accelerate,” for instance, the title’s broadcasted thrill is undercut by churning:

You are ringing and don’t line up. I advance, you acknowledge — enlarge — edge of this. I throat, you knee, I return to the gunboat and you had stolen it. Too many girls in a frame. Information portal, baseball bat. Box to box, stand. A clutch of girls too many, all over the television. Or newspaper. A dart and a back and forth, claim to a conscience. Here is my hand. Expended cabbage, conditional tender to you.

Here, the verbs start out active (“I advance, you acknowledge”) but progressively soften and dissolve, as if the poem is dissociating from the conflict it describes. Its resolution “to you” purports to be a diffusion of tension, a resting place, but its proposed hand also feels underhanded, its quieting unclear, like the gradual winding — up or down — of a crank.

This elusive tension between conflict and resolution, its need to slip, challenges the notion that compromise is a righteous endpoint, that peace is normative and homeostatic. Mediums, to that non-end, seen or unseen, are suspect everywhere in this collection, as is the very tissue of the text. Poems like “Couch,” a phonetic sequence that, to a native English reader, might feel more viscous than tedious, recalls the Jell-O-air of other poems, an odd continuity. “World Made Up of Pieces of Girls B, D, E and G,” spells out an elementary code on which the fabric of so-called fluency snags. Girl G, for example, “volunteers to be [a spiral], urg[solid circle]g Girl B to go for anti-[spiral]” and so on.

And why not?

In “Relations with Walls,” Girl A seeks “proof of bodily friction” — for proof of body, as much as of self/girl. Just as the phrase “I throat, you knee” in “Blow Up and Accelerate” violently conflates bodily presence and action, “Relations with Walls” exacts the proximity of extremes: “No wall, but wall.” Betweenness therein becomes suspect, so subject. But even betweenness is too settled, too in the way for Nakayasu, because it’s essentially ascribed by what it’s between. Only in flux, in parsing itself out, is an inch infinite, a thing free. Whatever the condition that threatens to designate, be it form, gender, or other script, Girl J, for one, “breaks it, and breaks it, and breaks at the cost of her own body, fetishized beyond recognition. Space opens, but she has no body left to fill.”

Some girls are girls insofar as they’re countlessly said to be. Some are also persons, psyches, beings, dummies, puppets, and proxies, each evolving by degrees, like placeholders for futures of themselves. Memories, perhaps, of the artists behind them, as Nakayasu cites seven collaborators. In other words, these some girls are sort of familiar: in sum, and in turn, like people. Or people-ish, anyway.

Whoever they are, wherever they are from, and, indeed, whatever they say or do, they are frank and frankly variable about it, and frankly, in their overt variability, maybe a bit overly vulnerable to bouts of interpretive revelry by their reader, who is likely prone to such revelry to be sitting with this book, or otherwise predisposed to walk straight into fog. To be sure, there is pleasure in this kind of reading that Nakayasu has so inventively and entertainingly wrought, from which you emerge just as bugged as bemused, freshly aware of vagaries and potentialities at the edge of jubilation and despair. It’s a fog that needs returning to, but not for reliving necessarily. Upon concluding, you may find that you’ve missed everything utterly. Something, somewhere, there was some kind of rapture? Only you can’t tell who’s been taken, who or what’s left behind.

Jed Munson writes from Seoul. His debut chapbook, Newsflash Under Fire, Over the Shoulder, is forthcoming with Ugly Duckling Presse.

This post may contain affiliate links.