What’s being conjured? Writing is like a crossroads, a Ouija board glowing sickly blue. When I heard that Logan Berry’s latest novel CASKET FLARE (Inside the Castle) had been written over the course of a three-day séance at the Skylark Motel in Chicago, it sounded like a lucrative opportunity to connect his overlapping worlds of text, image and performance. An author and theatre director, Logan Berry follows the infernal trajectories of his previous works—Transmissions to Artaud (Selffuck), his invocation of the poet-necromancer himself, and Run-off Sugar Crystal Lake (11:11 Press), an excavation of 80s summer camp slashers—towards their liminal ends in CASKET FLARE, a book conducted in ritualized time and space. I was interested in the fabric of this highly specific experiment as both lived experience and creative process. Body, text: each a matrix of ectoplasm. The book features an Emily Dickinson quote comparing the human brain to a haunted house: “One need not be a Chamber—to be Haunted— One need not be a House— The Brain—has Corridors surpassing Material Place.” A bathroom door at the Skylark left ajar, the dim frenzy of a Bluetooth speaker. A homogenous zone of motel apparitions. Invested in place, history, the occult and technology, CASKET FLARE drifts through many rooms.

Logan Berry spoke with me over Zoom before we conducted the interview via email. In addition to CASKET FLARE, we discussed his Sarcoma Cycle, a trilogy of plays: NANOBLADE 1998, SPRING BREAK 2020, THE MOURNING LIGHT 2050, which he plans to run in Chicago this year.

Matthew Kinlin: Let’s begin on the other side of the veil. If you could make contact and speak with three dead souls from history, who would they be?

Logan Berry: I wouldn’t; I’d wait for the dead to contact me.

There’s a Broadcast lyric from “A Seancing Song”: “Suns how they bloom, how they bloom in the room, in the room in the afternoon.” My understanding of CASKET FLARE is the book documents a three-day séance conducted in a Chicago motel, where you used a Bluetooth headset to capture your experiences with the speech-to-text function. Can you expand on what made you want to conduct this kind of experiment?

I wanted to write a book that is painfully present, that enacts its composition as it’s read. Found footage is the only genre of horror that consistently destabilizes me as I watch it. I wanted the textual equivalent of that. You’re complicit in the summoning. You descend with me.

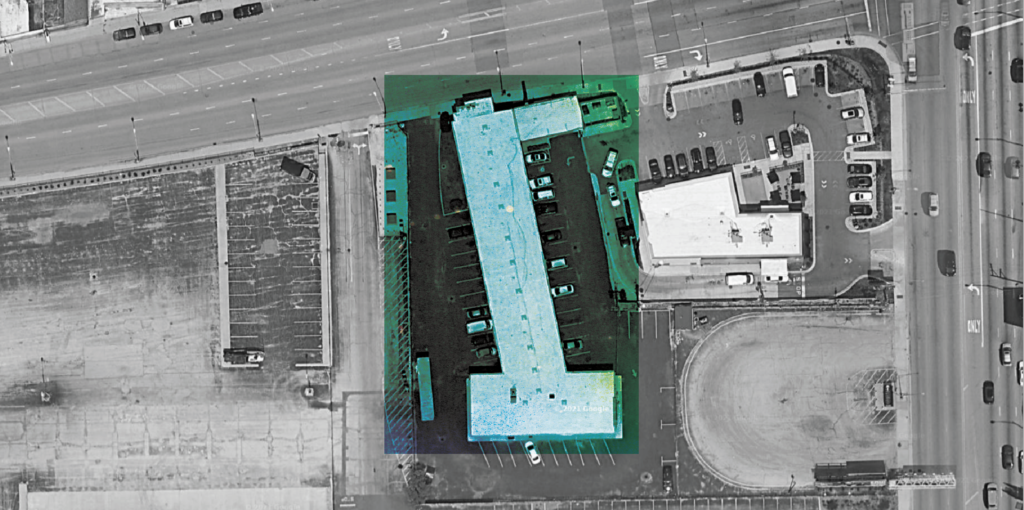

CASKET FLARE begins with a description of the location of Skylark Motel, where you held the séance, between the northern perimeter of the Chicago Midway International Airport and the Des Plaines River. The experiment feels invested in place, which took me to Guy Debord’s definition of a dérive, or a journey through an urban landscape, as: “a technique of rapid passage through varied ambiances.” Can you explain your choice of place and discuss any ambiences you encountered?

The Skylark was the only motel that hit my criteria both for pricing and location. It could’ve been anywhere, but it had to be there.

CASKET FLARE attempts to wrest the ambiences of the motel and surrounding areas into the text. What I couldn’t have predicted was experiencing the oldness of space, the ambience of the ancient; it’s all around us, hidden in plain sight. The future, too–it’s here.

CASKET FLARE feels like a deranged field study in parapsychology. It reminded me of Konstantīns Raudive with his electronic recordings of spirit voices. The book was in communication with this ghostly Other but also the reader. Additionally, the work details an invitation to contact you and emails from others about their own paranormal experiences. Can you expand on all these interpersonal, and interdimensional, dynamics?

A couple weeks before checking in to the Skylark, I blasted out an email describing the séance and my motives to a bunch of friends and colleagues. Their responses were varied and touching. Several expressed concern for my well-being, others described their own experiences with unexplainable phenomena, and others asked questions. I included their responses as a structural element, as breaks between sections, and to counterbalance the chaotic, inhuman forces in the book.

Imagining the reader in the motel with me, addressing them directly, happened impulsively. I did it to not lose touch with reality.

I enjoyed the use of Bluetooth and the overlap of business technology with spiritualism. Throughout lockdown, it felt like Zoom meetings became this global séance. There was a Montana doomsday cult leader called Elizabeth Clare Prophet, who believed herself to be the reincarnation of Marie Antoinette, amongst others. One of her mantras was: “I am, I am, I am the resurrection and the life of my finances and the US economy.” Can you expand on the relationship between the corporate and occult in your work?

I’m interested in affirming fringe and off-kilter hermeneutics of reality in my art and seeing where they go. British occultist Dion Fortune defines magick as “the science and art of causing changes in consciousness in conformity with will.” This definition is so capacious, it’s practically a worldview, and it’s troublingly hard for me to think of any aspect of corporations that doesn’t meet this definition of magick. While this is, on the one hand, an extremely enchanted worldview, it’s also extremely sinister: “What kind of magick?” is the obvious next question. “What’s being conjured, unbeknownst to me, by my work routines?” “What shapes are traced in space by my posture at my desk? By the paths I take to use the loo, to have a smoke, to take the train home?” “For whom or what do I sacrifice my flesh and time?” This is a deeply paranoid, unbearable way to live, and it fuels my writing.

In Samuel Beckett’s Not I, Mouth expresses: “no idea what she’s saying . . . imagine! . . . no idea what she’s saying! . . . and can’t stop . . . no stopping it . . .” It seems that CASKET FLARE taps into something about writing as allowing something else to speak, often the invasion of an alien entity. How do you see the relationship between channeling and writing?

I’d wager that all writing is channeling, to greater and lesser degrees, though what is being channeled is worth considering.

Throughout the book, you invoke and speak with the entity of Q: “I beseech thee, Q.” Can you describe how you understand Q in CASKET FLARE?

“Q” is the catchall name I use for the sundry strange phenomena, hallucinations, and visions that drove me towards CASKET FLARE. It’s a quick way to address them all at once. And I like the shape of it—the “O” as a circle or sigil, the squiggle off the bottom right as an entry/exit into/from the circle.

You thank Q Lazzarus at the end of the first section of CASKET FLARE. People often have a strange and personal connection to her single “Goodbye Horses.” How does that song make you feel?

It makes me feel like I’m about to locate something I’ve been missing for a very long time.

The architecture of the book is divided into two sections with visual elements throughout, including Polaroids taken during your time at Skylark. Can you discuss your collaborative work with Mike Corrao on the project, and John Trefry, and how the visual language of CASKET FLARE developed?

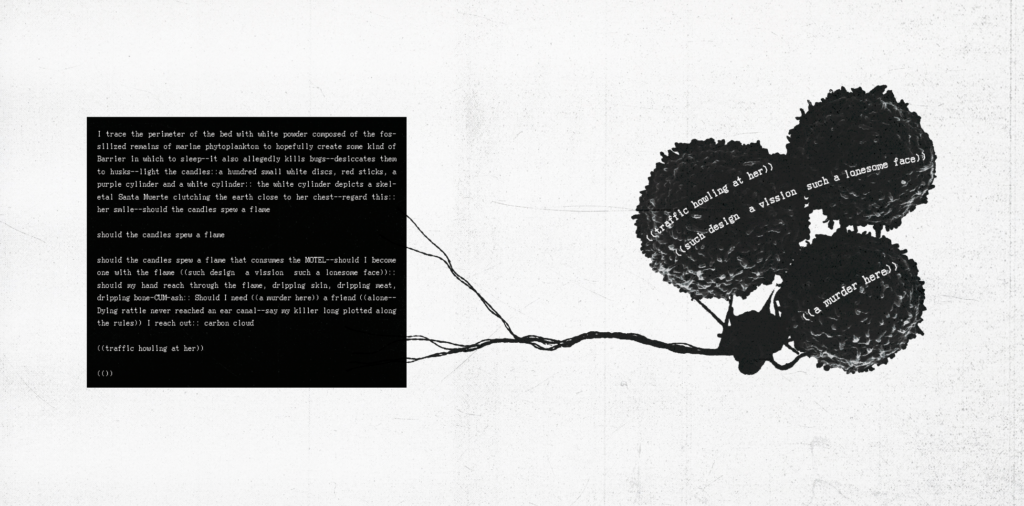

The visual language developed alongside the textual language. At 11 PM in the Skylark, I’d compose for thirty minutes via the Bluetooth headset, then I’d spend thirty minutes editing and designing, and repeat the process till morning. The original manuscript I sent to John was a massive, fugly Word doc. Mike painstakingly recreated it with a much higher standard of execution in InDesign. We then sent the book back and forth to each other with notes, ideas, and questions, which led to him adding a ton of textures and elements.

John’s main note on the original work was that the strange, unexplainable disruptions in the text transmissions (which I’d bracketed off in ((double parentheses)) as they appeared because I didn’t expect them and didn’t know what to do with them) needed to be more clearly defined. I sent him a couple of options: one where the disruptions formed textual frames around the main text, and one where they were installed inside of cancerous shapes adjacent to the main text. He said he liked them both. Mike and I decided to roll with the latter.

Your writing often invokes very saturated colours: cryogenic greens, garish pinks that take me to films like Stuart Gordon’s From Beyond. In his theosophical writings, Charles Webster Leadbeater felt colours denoted parts of the astral body: light blue denoting high spirituality, brown with red streaks: jealousy, bright yellow: intellect. Can you discuss your relationship with colour? Are there any colours you are more drawn to?

I love color. I’m not well read on their symbolism, so my usage is instinctual. I don’t have a single strategy or principle for colors in either my books or my plays, but maybe I should. Generally, I like high-impact moments of color, where things can really pop.

My day-to-day attraction to certain palettes is situational. For example, my daughter is nine months old, and I hate the trend of muted colors in baby’s clothing. They’re babies—why would we want to dress them in the colors of cell phone cases and corpses? Their clothes should be joyous and vibrant! But I wear all black almost every day.

The striking images in the text offer divergent influences, from decadent literature: “the first neuronic jewels strung through Lunacy’s necklace,” to cyberpunk: “the infernal ATM through which we’re squirted.” CASKET FLARE feels like a summation of many elements, particularly as it also involves the performative aspect of your time at Skylark Motel. Can you speak a little about how text and performance operate in the same work?

I think it’s probably impossible for them to coexist in total harmony. The temporal situation of a performance is completely at odds with what a book is. Is it possible to freeze the ephemeral? To textualize liveness? I don’t think so, but CASKET FLARE attempts to.

That brings me to your Ultratheater project, and the Sarcoma Cycle: a trilogy of plays you are planning to stage. If you could offer a manifesto for Ultratheater, what would it be? And can you expand further on the Sarcoma Cycle? I know in Transmissions to Artaud you called for a move towards an unnatural theatre.

I’ll start with the Sarcoma Cycle. It’s a trilogy of plays, set in three distinct time periods and genres, connected by themes of death and technology. The three plays are NANOBLADE 1998, SPRING BREAK 2020, and THE MOURNING LIGHT 2050. The same seven actors will appear in all three plays. We’ll be running them in repertory at the Color Club in June. It’s the first repertory production in Chicago in a decade, and we’re doing it on a shoestring budget. The actors and crew are ridiculously talented. It’s going to be insane.

A manifesto is forthcoming, but here’s a provisional stab at a description: Ultratheatre attunes to the hyperbaroque structures undergirding contemporary society and attempts to dramatize them in relation to cosmic forces like sex, death, delirium, dreams, and time. Its toolkit is vast. It avails itself of all historical theatrical movements, incorporating them as gestures and textures, rather than monolithic templates. (It’s no longer enough to perform an “absurd” play, for example—who gives a fuck?—absurdism is a strategy that can be used and abandoned in an instant.)

It also avails itself of theatrical aspects of twenty-first century that haven’t been well-integrated into the theatre: public relations; self-presentation online; memetic feedback loops; perception management; groupspeak, doublespeak, and wrongspeak; the staginess of reality via algorithms, focus groups, psy-ops, social media, and statecraft. Ultratheatre isn’t producing plays about these subjects necessarily (though it wouldn’t be a problem if it did); rather, it takes formal cues from them, incorporating their structures and dynamics to create something fresh and vital, in a specifically theatrical idiom.

It’s a mammoth, fractalizing aesthetic and thoughtform. It’s not “against” anything, especially naturalism. Naturalism is an excellent modality for setting the stage and letting the audience settle into the rhythm of a play, before the winds change, the maenads scream, and the ritual commences.

Ryan Trecartin once said: “Our generation was ready for something like YouTube ’cause we already had it in our logic and in 2005 when it came out—I think it totally changed how people think about the ways in which people act in my movies, like new technologies create different qualities in understanding and presenting ourselves performatively.” How would you imagine a theatre of 2024?

A theatre of 2024 understands that audiences enter the theatre with a zapped attention span and a sophisticated relationship with the fourth wall from decades of media consumption. It respects their time by delivering something they’ve never seen before, that could only be experienced in a live setting.

Giorgio Albertazzi as X, wandering through the glamorous hotel of L’Année dernière à Marienbad, catalogues what he sees: “Empty salons. Corridors. Salons. Doors. Doors. Salons. Empty chairs, deep armchairs, thick carpets.” If you could haunt the corridors of any building, other than the Skylark, where would we find you?

I’d love to say you’d find me in Bertrand Goldberg’s brutalist masterpiece River City in Chicago, the Blue Hole in Santa Rosa, New Mexico, the Horseshoe Casino in Hammond, Indiana, one of the cathedrals in Tulsa, Oklahoma, or any 7-11—but if I’m being honest with myself: the Mountain View Lodge in Bozeman, Montana. It’s a perfect motel.

*

Matthew Kinlin lives and writes in Glasgow. His published works include Teenage Hallucination (Orbis Tertius Press), Curse Red, Curse Blue, Curse Green (Sweat Drenched Press), The Glass Abattoir (D.F.L. Lit) and Songs of Xanthina (Broken Sleep Books).

This post may contain affiliate links.