[Soft Skull; 2021]

Do we dare mention the stable self that grounds our perceptions and knowledge of the world? Is our experience of coherent selfhood best understood as a simulation? If we cannot access reality outside of the human apparatus of perception, is simulacra then the foundation upon which we construct ‘reality’? Pilot Impostor brings refreshing wit to these questions. In this book of images, poems, and prose pieces, James Hannaham reflects on how we know the world and confront the failure of others to consider our singularity. He writes, “I’ve seen myself as several things when someone else saw only one and I used a word unknown to those outside.” We are also the impostors of our own existence: “I have impersonated things that I never become. But everything I did become, I faked at first. (Some things I might still be faking).” The mimetic power of appearance and performance unleashes a creativity, which refashions identity. The impostor sustains agency, decision, and responsibility. We pose. We become. We undo. We skirt expectations and evade labels. We reinvent and see the world in a new light. And so, the myth of authenticity shows itself as a network of interests, a grid fastening in place a convenient order of things that serves existing power relations.

We reconstruct our narratives, and yet also fall back onto repressive ways of thinking, rather than attempt to restructure our vision. Pilot Impostor emphasizes how myopic viewpoints often cripple our experiences, so working on liberating and expanding our perspectival range is key. Do we do this by reframing the concept of identity? The instability of everything defining us should be embraced. Yet, this is also a frightening prospect, and here the concept of disaster becomes relevant. History is filled with self-fashioning myths used as oppressive weapons, Eurocentric grand-narratives being one example. The myth of selfhood is also a power of labeling possessing catastrophic reach as it goes about categorizing identities. What does it mean to inhabit individuality? What does it mean to be a poet or artist? There is the obvious smallness of human life when compared to the colossal scale of the universe that Hannaham asks us to contemplate, but there is also just this one life we possess – and the individual and collective choices we make. Pilot Impostor considers disasters emerging from historical contexts and shows how everyday interactions bear the marks of transtemporal struggles and violence.

At its center, the book engages with the poetry of Portuguese writer Fernando Pessoa and the violent historical legacy of Portugal. Hannaham captures the national silences of present-day political Portuguese discourse. The representation of Portugal’s history of enslavement, colonialism, and fascism is still very much concealed in exalted euphemistic phrases such as “The Age of Discovery,” which is how the Portuguese name their epoch of maritime imperial expansion. At least in mainstream society, Portugal has not yet fully acknowledged the destruction caused by its past as enslavers and brutal colonists. Consider the recent visit to Senegal in 2017 of Portuguese president Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa and his hesitant refusal in apologizing for slavery when visiting Gorée Island, an active slave port in the 15th to 19th centuries.So, Hannaham reminds us: “The Portuguese began the Atlantic slave trade in the 1500s and, somewhere along the way, began to justify the practice with an ethnocentric bias against sub-Saharan Africans already available to anyone.” And later, in a piece entitled “Age of Discovery,” he writes, “Nobody discovered much of anything. They walked into a furnished apartment during a party and said, ‘Mine. Get out of my apartment, work for me at pitiful low wages — if any — or die.’”

Hannaham engages with Pessoa’s writing across the latter’s complicity with this indefensible romanticization of the past, mainly in Pessoa’s nationalistic poem A Mensagem (The Message). But he also evokes the existential Pessoa, the skeptic, an urban dweller and observer of people, and the Pessoa of psychic reinvention seduced by unending gestures of proliferation. This Pessoa releases a vertigo capable destroying the damaging Western myths of coherence:

You must accept that my identity is whatever I say it is. But the I that I am consists of an ever-changing mystery, a marbled swirl of oily rainbows and pond scum, a combination many-headed hydra, riddling sphinx on Ritalin, and multifoliate Medusa. What I say my identity is might not be what my identity is. I might be in the process of reinventing identity itself. I can say things about my identity that, if you say them, I will deny, and which, if you say them, will offend me, even if true. Especially if true. I reserve the right to change my identity before my mouth has finished describing my identity.

By alluding playfully and critically to several poems, Hannaham responds to the most well-known of Pessoa’s heteronyms: Alberto Caeiro, Ricardo Reis, Álvaro de Campos, and Fernando Pessoa as ‘himself.’ Pilot Impostor is roughly organized by these responses to the heteronyms. The book culminates in an engagement with A Mensagem — the only work that Pessoa published in his lifetime during the dictatorship of António de Oliveira Salazar and unsurprisingly admired greatly by the dictator. It is a series of poems praising the glorious past of the Portuguese. Hannaham titles this section “Mensagem de Erro” or “Message Error” and responds directly to Pessoa by rewriting and critiquing the ideological position of several poems in the book.

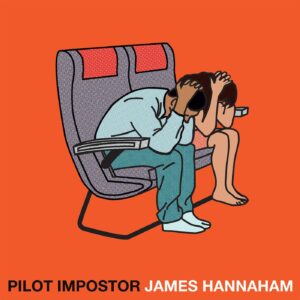

The artwork in Pilot Imposter reminds me of Johan Grimonprez’s seminal film Dial H-I-S-T-O-R-Y (1998) with its images of planes, cockpits, wreckages, blue skies, ads, and maps. Yet, I also appreciated the more abstract images inspired by Portuguese azulejo, which to me stood as an invitation to imagine less tragic results for our becomings. Pilot Impostor ends by contemplating what lies in the future for our gutted, wounded world, even if our planet exists in a kind of geological indifference “to all of our frivolous cares.” Can we trick more hopeful outcomes into existence? Will our talent for deception finally be directed toward worthy ends? Hannaham leaves this question hanging as he announces “There’s no real frontier to which humans are heirs.”

Isabel Sobral Campos’s books are How to Make Words of Rubble (Blue Figure Press, 2020), and Your Person Doesn’t Belong to You (Vegetarian Alcoholic Press, 2018), Other works include Material (No, Dear and Small Anchor Press, 2015), You Will Be Made of Stone (dancing girl press, 2018), Autobiographical Ecology (Above/Ground Press, 2019), and Sobriety Crystal (The Magnificent Field, 2021). Her poetry has appeared in the Boston Review, Brooklyn Rail, in the anthologies BAX 2018: Best American Experimental Writing and Poetics for the More-Than-Human World, and elsewhere. She is the co-founder of the Sputnik & Fizzle publishing series.

This post may contain affiliate links.