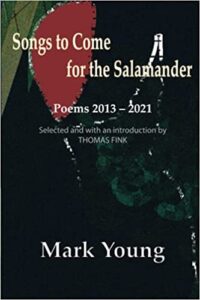

[Sandy Press & Meritage Press; 2021]

“‘Bricolage,’ more than anything else, is the term I would use to best describe my poetry.” Mark Young

/brikɘlȁZH/ : something constructed or created from a diverse range of available things

Mark Young is an internationally-recognized writer — creator of vispo and text-based poetry. He also is editor of the online and print journal, Otoliths, publishing experimental literature and innovative visual art. A New Zealander living in Australia, Young is author of scores of books, and his widely-read blog, Series Magritte, is dedicated to and inspired by the Belgian Surrealist painter, René Magritte. Young has been featured in jacket 2 and other well-regarded venues, as well as, by the Poetry Foundation. His vispo work, les échiquiers effrontés (2018, Luna Bissonte Prod), grid poems based on the work of Surrealist artist Marcel Duchamp, is a collector’s item. The improvisational meters and rhythms of jazz characterize Young’s work, and William Carlos Williams, Charles Olson, Ursula K. Le Guin, and Jorge Luis Borges are among his literary influences.

Songs to Come for the Salamander (hereafter, Salamander), is an experimental work — a compendium of “associative writing,” primarily short poems, but, also including a few longer compositions and prose poems. The collection’s Introduction, written by Thomas Fink, is an exhaustive, informative, and scholarly, though not pretentious, assessment of Young’s oeuvre. In Fink’s words, “One of Young’s major gifts to his readers is to provide . . . alternatives through wild, dazzling juxtaposition of elements that comprise his poetic bricolage.” Many articles and books have attempted to answer the question, “What does ‘experimental literature’ mean?” The Russian Formalist, Viktor Shklovsky, proposed that experimental art is a technical “device for making strange” and that experimental writing draws “attention to the use of common language in such a way as to alter one’s [sensation and] perception of an easily understandable object or concept.” Young’s work functions as just such a device. For example:

If there were other

entrances to the cage

of the dancing bears

I might not have to

always climb sideways

into this cannon & be

fired in an elliptical arc

towards the trapeze . . .

In addition to his blog, most of Young’s works belie his learned interest in Surrealism, and that movement’s historical precursor, Dadaism. In 2019, I asked the author how he became interested in these movements, and, via e-mail, he informed me that he “came across Giorgio de Chirico & Magritte’s paintings almost sixty years ago — de Chirico first, I think. Plus, the movies of [Luis] Buñuel which I first saw even earlier.” Young went on to say that he was first exposed to Surrealist journals while in high school at an “incredible secondhand bookshop in Wellington, New Zealand, across the road from the stop where I caught a bus.” There, he became familiar with “collections of poetry by Paul Eluard & [Guillaume] Apollinaire & [Tristan] Tzara, & the novels Nadja by [André] Breton & Hebdomeros by de Chirico, none yet available in English. I spent long nights translating them, loving what I found, & trying to write poetry in French at about the same time I started writing it in English. I published translations of Eluard & Robert Desnos & Apollinaire in those early years.” Clearly, it is no exaggeration to say that, since an early age, Young’s “roots” have been embedded in the history, practice, philosophy, figures, and creative outputs of the Surrealist movement.

Surrealism’s founder, André Breton, stated that the movement’s goal was to “resolve the previously contradictory conditions of dream and reality into an absolute reality, a super-reality.” Surrealism, derived from the explicitly political movement, Dadaism, was influential in Europe during the Interwar Period, a time of worldwide disruption, as well as innovation and progress. In America, the “Roaring 20’s” were ongoing, and social, as well as, economic mobility, were available to citizens of many countries. Automobiles, electric lighting, and the radio were accessible to the average person, and dependence upon fossil fuels increased. During this period, also, the world experienced the expansion of Russia on the global stage, as well as, the rise of Communism — reflective of Modernism’s emphasis upon Grand Narratives.

Surrealism, originating in Europe, has been described as a project mining “the key to dreams” and “symbolic images.” Sigmund Freud’s text, Interpretation of Dreams, was published during the Interwar Period, and Psychoanalysis was a foundational source of inspiration, method, technique, and ideas for the movement’s artists, particularly the exploration of nocturnal events, of hypnosis, of “automatic writing,” and of “free association.” Excavating the Psyche, symbolic images, and primal events, including the historical record, was more important to Surrealists than documenting current events, though, reminiscent of the intentional and direct political goals of Dadaism, Surrealism was indirectly political in the sense that it violated expectations and operated as an anti-establishment force. Mark Young’s “associative poetry” follows these traditions and is characterized by Surrealist signatures:

I walk out to

find asemic snail tracks

on the rubber mat at

the bottom of the

backdoor steps. Two

yellow butterflies

map the yard, one

serving as a center

whilst the other

circles round it.

Broken branches

pointing in all

directions. Is the wind

singular or plural?

Like other Surrealists, Young’s art embodies juxtapositions of seemingly contradictory elements, indeterminacy, the “irrationality” of collage-like components (see harry k stammer’s cover image), “absurd reality,” and weird connections of common objects. Despite its associative nature, Young’s poems are not literally created automatically, since, as the poetry critic Marjorie Perloff pointed out, even experimental writing is an “intentional” act or “choice” by the author. In the final analysis, however, Velimir Khlebnikov’s statement is a cogent reflection on the Surrealist project: “There exists no science of word creation.” Unpredictability reigns over predictability: “MICE — meetings, incentives, conventions & / exhibitions — become a hazard for drivers.”

Other features of Young’s writing place him squarely within the Surrealist tradition, yet, at the same time, reveal and preserve the poet’s own identity. Characteristically, Young’s titles and text are disconnected and illogical in a manner that permits, indeed, requires, each to stand on its own. This independence belies an interdependence of linguistic rank and, though the collection includes a few prose poems, most of the compositions are short, giving the appearance, again, of non-hierarchical status and emphasis between title and text. In this sense, Young appears to be making a statement about the preference and primacy of egalitarian structures. Related to this, the poet is unclear (ambivalent?) about the “voice” of many poems, as well as the idiosyncratic use of punctuation and spelling — again, preserving Surrealist traits of mysteriousness and indeterminacy:

So he gave due deference to his elders, &, in return, was given such tasks as language teacher or book shelver &/or cataloguer, each with its small emolument that helped pay his way along the path of study he had decided to follow. He himself was clear about the direction, but to those who employed him, he only offered up that which they wished to hear…

In other poems, yet rarely, Young employs the lyrical (Formalist) “I” — while retaining Surrealist signatures: “I wake up late. / Dylan Thomas is in the bed beside me. / He smells of liquor. / I am about to throw him out when he starts speaking….”

Young’s “associative,” collage, style is reminiscent of Magritte’s words: “One object [word, phrase] suggests that there is another lurking behind it.” Because of these layered features, the poet’s compositions embody “interpretive power,” to use the poetry critic Helen Vendler’s term — the ability to be read over and over, combining and re-combining elements, so that multi-level effects are achieved. With these conceits, Young reveals not only Surrealistic traits, but also postmodern ones whereby inference and meaning are fractured, surrendered, left for the reader to interpret — or not.

In his Introduction, Fink describes painter Magritte as an artist devoted single-mindedly to his work, and, due to his exhaustive output, one imagines Young to be the same. Young’s writing has been called, “experimental, stochastic, poetry,” and Salamander exposes him to be our ranking poet in the Surrealist tradition writing in English.

Clara B. Jones is a knowledge worker practicing in Silver Spring, MD, USA. Among other writings, she is author of the collection, Poems for Rachel Dolezal (GaussPDF, 2019). Clara, also, conducts research on experimental literature, radical publishing, as well as, art and technology.

This post may contain affiliate links.