I had the good fortune to meet Kevin Phan in the summer of 2011. If I recall correctly, the occasion was a welcome picnic for the start of our MFA program at the University of Michigan. Our backgrounds are so radically different, and I will forever be grateful to UM for—among other things—bringing us together. I think it is safe to say that Kevin and I are both introverts, and we naturally gravitated to each other over the course of our shared experience of attending class, readings and roundtables. We both had an affinity for the outdoors and philosophy. We could also both sit with feedback for a long time. We’re mullers. And we also enjoy poems that are shapeshifters. It’s a shame that we live so far apart these days, but I feel the universe has done us a solid by allowing our books to arrive in close proximity and facilitating this conversation—part catch up session and part craft jam.

Benjamin Landry: Kevin, I just finished reading your collection, and these are gorgeous prose poems. They are open and lush. I could not remember if I saw any of them as first drafts back in MFA days, but some of the turns of phrase seemed familiar—maybe because they are so thoroughly infused with “Kevin-ness.”

You and I spent a fair amount of time in the early twenty-teens hanging on porches and in bars in Ann Arbor. I think what I liked about you is that you are a man of many interests and a good listener. Both of those qualities come across in these poems, as in “[What fool denies the inner life of a whale?]” when you explore metaphysical conundrums, generate “applause for the riffraff,” tackle prison labor, make a dad quality joke and make a serious ecological point. It is impressively far-ranging. But you have a reassuringly laid-back demeanor. Where does the poetic effulgence come from? Is that something you can put your finger on?

Kevin Phan: Ben! Yes, I had a wonderful time bonding with you at Michigan. Our porch hangs were amongst my favorite moments in Ann Arbor, with your daughter toddling around on the lawn, the air humid, low hanging. Our conversations in those days were more jazz than philosophical theorems. Our chats always felt sprawling and fluid. And because you were more accomplished than me at that point— more publications, more insight into the “industry,” better read—I always regarded you as my poetry big brother. It’s truly a wonder to reconnect.

The poems in this, my first full-length collection, are barely present in my MFA thesis. A few short sections were tacked onto the end of my thesis, which is where this book begins (the first four sections or so). The book began as an aubade, a meditation on gratitude, meant to be simple, purely observational, skimming along the surface of moment-to-moment insights. Fast forward several years. So much had changed. My mother was diagnosed with bone cancer and soon passed away. Trump was president and families were being separated at the border. Meanwhile, climate change and species eradication seemed only to be intensifying.

Nearly all of the first drafts of these prose poems were written within a year of my mother’s passing, and this collection was my attempt to braid all of these concerns into a far-reaching tapestry with my Buddhist spiritual practice as the bedrock. I felt like that year was unceasingly overwhelming, and rather than isolate and focus on a few isolated incidents, I gave myself permission to allow most of that year into the collection.

While your experience of my collection probably felt new, I must say there is much in your collection (which began with your MFA thesis) which felt like re-encountering old friends. The title of this collection hasn’t changed. “Meep Meep,” “Pina,” “Mercies in the American Desert,” “Aquarium,” “Night Vision,” and other poems in this book are directly from your thesis, sometimes with only minor edits (as far as I can remember). Yet this collection feels both politically charged and emotionally accessible/expansive. I found many of these poems deeply touching because, as Cole Swensen describes in her blurb, these are “openly compassionate poems.” Is there anything that you’d like to say about the evolution of this collection? Were there experiences between MFA poetry camp and today that shaped your manuscript’s evolution? And what role did your editors play in shaping what became this absolutely wonderful, gorgeously rendered book?

Thank goodness for the jazz, rather than the philosophical theorems! We certainly got enough of the formal stuff in school. You are very generous in your recollections, Kevin. Also, it is funny to be described as a “big brother” (particularly coming from an old soul like you), since I have always been the young brother in my family. You have to understand that I was a late starter in the poetry world, and so I have always pushed myself to try to make up for lost time.

When I wrote some of those poems that would later go into Mercies, I thought of them as one-offs. My first collection was already in production, and that was structured on the periodic table of elements. I was looking for the next big organizing idea and still perhaps trying to avoid writing a more amorphous “collection.” I had just become a father but didn’t want to feel pigeonholed into writing poems about fatherhood, for instance. But some of the pressure was taken off by the publication of that first book and the second, Burn Lyrics. By that point, I felt like I had done the conceptual thing and I could relax just a bit. Be more “emotionally accessible expansive,” as you put it. So, some of the subsequent poems may feel more candid. But I have to say that I still feel my writing self is another entity entirely. The speaker is always me/not-me, even in the most ostensibly lyric poems. It is quite freeing.

So much changed between those years and the publication of Mercies. We moved four times, all of those moves precipitated by my wife’s work. I had to do a lot of scrambling to try to find jobs wherever we landed. I think the transience, anxiety, sense of beauty on the move, are apparent in the first and second sections of the collection. But the third section is something else.

When we were living in Oberlin, Tamir Rice was killed by police not far from us in a suburb of Cleveland. The racism, cruelty and violence that are just as American as any of the other laudable claims this country makes about itself really registered for me. This was, of course, confirmed by the 2016 election of a president who unabashedly championed those iniquities. My wife, Sara, started a chapter of a social justice group. We marched, wrote, called, advocated, petitioned our representatives. Protested outside their offices. We recruited and supported challenger candidates. We lost a lot of sleep and worried about raising our child in such a conservative stretch of Northern New York, where some of the biggest employers are prisons. I must admit that sometimes I wrote angry. You can see some of that frustration–a sense that this country is squandering its great promise—in poems like “Neighborly” and “Parkland” and “How Many Will Be Too Many” and “Gina Haspel and the Honey Bee.” They aren’t polemical—nobody likes being told what to do—but I hope that they serve as effective mirrors.

You asked how editors shaped the collection. LSU has been absolutely wonderful—and relatively indulgent. But one of the readers of an early draft raised flags about a selection of movement-based poems, about twenty pages altogether, that was interrupting the manuscript. I love those poems, and I hope that they will appear in a future collection, somehow. But when I took them out, I was suddenly well shy of a full manuscript. So, I had the incentive to write a whole bunch of new stuff—some of it playful, some of it rather serious. It was a pleasure to suddenly have that liberation and onus right at the end of production. I always seem to do my best work with imposed parameters and deadlines, which is perhaps why I enjoy conceptual work (and your prose poems!).

I am so sorry about your mother’s passing, which sounds to have been physically and emotionally grueling for her and for you. I read that line about you crying into a Big Mac in an airport on the way to your mother’s deathbed, and I thought, isn’t that grief, exactly? The soul/self in agony but the body compelling us to go on? Did you write during the process of losing your mother, or was it only something you could bring yourself to do much later on? Was poetry a consolation for you at the time? Do you turn to Buddhism and poetry simultaneously? Also—I hope you don’t mind my asking you this, but as an atheist, I am curious—I have perhaps a preconception that Buddhism offers some excellent guidance in living. Do you find it offers the guidance you need in thinking about death? Were you and your mother able to achieve a sort of understanding across your difference in faith? And was your conception of faith changed in any way by helping her in her passing?

Thanks for the condolences. Yeah, the grind and depletion that accompanies a terminal diagnosis and rapid death feel nearly all-encompassing. In one of the poems, I write about a transgender woman named Shar. Adam Sekuler made a documentary about her as his thesis project at the University of Colorado, and the documentary tracks her decline into Alzheimer’s. After, her wife gave a Q and A about her relationship with Shar. One audience member asked, “What’s next for you in your life? Will you look for new love?” Her answer was telling.

She said that she had spent six months after Shar’s passing mostly lying in bed, unable to rouse her energy to go about her day-to-day life, barely able to function. This is the first time I had heard anybody speak so honestly about the physical exhaustion that accompanies grief. How it lodges in the body, clogs the passage of energy like plaque in a plugged shut artery.

This mirrored my own experience while my mother died and during the following year. The struggle to wake up each day was real. I began this collection just after my mother’s diagnosis. I took a month off work to take care of her in Marion, Iowa. My mother developed bone cancer in the jaw—probably the result of a lifetime of smoking cigarettes—so the surgeons had removed the cancerous section of bone from her jaw, then cut out a section of bone from her lower leg to replace the missing section. So my father and I were caretaking my mother—sponge baths, applying medical gauze, etc. My mother didn’t have much of a spiritual faith, though my interest in Buddhism had invigorated her exploration. She loved Pema Chodron in particular. Often, we’d listen to guided meditations about loving-kindness or centering your thoughts in your body. This seemed to help.

Yet, the doctors failed to get the cancer under control. It spread throughout her body. And three months later, she was dead. Shortly before, she was visited by a priest while she was in hospice. He asked her about her spiritual faith. She said, “Christian,” and almost immediately sent him away (I’m told). Uninterested. My sense is that my mother was profoundly unhappy with her Catholic upbringing. And because she suffered from severe depression, I suspect she never felt worthy of being saved. She enjoyed reading about Buddhism, but her experience was entirely through books and YouTube videos.

Though I’ve not read it, I’m told the Tibetan Book of the Dead offers guidance about the intersection of Buddhist faith and death, detailing the transmigration of the soul, karmic rebirth, and what a practitioner should be thinking about as they pass. Yet I’m a Buddhist atheist, so neither my mother nor I truly believe(d) in an “afterlife” / “karmic rebirth.” I was reclining in a lounge chair next to my mother at 5:30 a.m. at the moment of her death, listening to her jagged breathing, and then her breathing stopped. My immediate thought was that there is no rebirth; we’re just our bodies. I doubled down on my commitment to use my energy to benefit others. Throughout my life I was primarily interested in the intersection of social justice and Buddhism, anyhow. Even the Buddha responded to a question about life beyond the grave by saying—and this is me paraphrasing—fuck-if-I-know.

So Buddhism helped me to stay rooted in my body. Meditation helped me to process grief and not get too freaked out. Listening to guided meditations helped situate my own grief within the ecological grief of climate change alongside the many griefs of Black people being singled out and assailed. This book was writing as an act of survival.

It’s interesting that you and I had similar experiences with our editors, albeit at different presses. Your editors seemed to say, take out this chunk of poems and write some new works and it’s a go. My editors, Stephanie G’Schwind and Donald Revell, said take out five prose poems and replace them with five or so new works and that’s a wrap. Praise be to editors who trust their authors!

I wanted to pick up on this idea of “writing angry,” as you’ve described. First, thanks for doing the hard work of organizing, protesting, and calling your reps while scrambling to find jobs through your various moves and raise your daughter. That’s passion. That’s commitment. Like much of the nation, myself included, the Trump presidency was deeply unsettling. Yet what strikes me about your angrier poems, found mostly in the third and final section of your book, was how the quality of the writing didn’t wane. These poems are rich, deep. My favorites in this collection. Audre Lorde says we must use our anger, and not be used by our anger.

Was it a challenge at all for you to write these pieces while maintaining consistency with the collection more broadly? (Was this even a concern for you?) Do you have any advice for the readers on how to translate anger into art? Do you feel that, in writing these poems, you were able to relieve the pressure on your imagination or experience any form of healing from the collective traumas of the Trump presidency?

I am not sure that writing angry necessarily serves a therapeutic function for me. But since there is a baked-in dramatic tension, these poems do seem to arrive in one propulsive moment. This is in contrast to most of my poems, which are usually written over the course of a few days. So, these poems are sustaining in a different way. They also work as signposts and goads against complacency: This is how you felt when X happened, and don’t forget it. At the time of their conception, I was not concerned with how they might complicate the collection. I think—I hope—my poems tend to be stylistically varied, anyway, which is an admission that I am just a human of many moods, often surprised by memories, qualities of light, things people say, things I am reading, flashes of the sublime in the natural world. That said, I did make a conscious effort to place the “angrier” poems in the latter portion of the collection, both to give the reader some fire as they leave the collection to confront the world but also to avoid the situation of moving back and forth between introspective and more topical work, which would have been the case had I distributed them more evenly throughout the collection. It would have seemed deliberately manipulative to do so—to lull a reader into meditation only to slam doors in the house via cultural critique.

In terms of those who wish to translate their anger into art, I say by all means, go for it. Aren’t there a million riskier things we could do with our anger? And it might just result in keener work. Of course, in writing about real events, I feel it is important to avoid sensationalism and exploitation by, say, not inhabiting a victim’s perspective during a moment of trauma. No one else can credibly claim this territory: it is sacred. Also, there is a bright line between art instigated by violence and art which participates in violence. Anger certainly raises the stakes for an artist. Which I suppose is why a lot of poetry sticks to the beautiful.

But hey, Sir, don’t I detect flashes of anger in your own work, from ecological alarm to resentment at the body’s betrayals? At least, that is part of how I interpreted lines of yours like, “We live with no true sense of how our worlds became. and to bear witness is to be alive within our cuts.” Maybe I am projecting.

What you wrote about your mother not feeling “worthy of being saved” was profoundly sad. But it makes me think of all the ways in your poetry that you attempt to honor your surroundings, both manmade and natural. You have two poems entitled [I didn’t even get the chance to kiss you goodbye] that follow the chronicle of your mother’s passing in the collection. These two poems are gently guided lists of extinct bird species, and I like how the text—the spoken word—becomes a monument to each passing genetic line. I wonder how you feel about poems and their abilities to memorialize. Do they stop time? Do they enact time?

You say that writing this book was, for you, an act of survival. My sense of these poems is that they are exceptionally aware of the present, and in this way, they court the future. There is not a lot of dwelling on memories much further back than your mother’s illness. Was that a conscious decision? Is this your habitual approach to living or writing? Were there a whole bunch of more retrospective poems that you weeded out as you constructed Dears, Beloveds?

You told me once that you like working outside, and I know that the majesty of Colorado has long had a hold on you. I just want to note how successfully this collection suggests—paradoxically, in the relatively confined space of a justified prose poem—the expansiveness of the outside world: it is quite a feat. To read these poems was like catching up with you, going on a hike maybe, with each prose poem occasioned by the progressive reversal of a switchback. The views are both forbidding and tremendous. Thanks for taking me along!

You mention that you situated many of the more “topical poems” together in the third section of the book so that the reader doesn’t feel ambushed or manipulated by the sequencing of these poems. That’s so incredibly thoughtful and a considerate way of sequencing a collection. It’s a wise, sage move. And it’s exactly the type of gesture that makes me once again express that I consider you a literary big brother! You’ve created a structure that compassionately considers your reader’s experience. That’s empathy. That’s respect. And I know that I, personally, feel grateful for the journey you’ve taken me on in your collection. It feels so wonderful to once again get acquainted with your brilliance, insight, honesty, and deep knowing. There is a Buddhist deity from the Mahayana tradition—my spiritual tradition—named Manjushri. In Sanskrit, his name translates as “Gentle Glory.” This deity wields a flaming sword that cuts through ignorance and duality to reveal transcendent wisdom. That’s you. That’s this collection.

And yes, there certainly are moments of anger in my own collection, for sure. The angriest poems—five in total—were nixed by my editors. Donald Revell warned in an email, “Including these poems in the collection guarantees the collection’s transience.” Honestly, they were poems that directly confronted the racism of Donald Trump. My tone was mostly mocking, and I was so emotionally hijacked when writing these pieces that they probably deserved to end up in the trash bin. The fiery moments that made it into the final collection meditate on ecological, biological, and social injustices that complexify our present moment.

You ask a great question [about retrospection]. I didn’t make it back very far in history before my mother’s diagnosis. The collection was accepted for publication as I was just finishing the first draft. I didn’t even consider the book complete when it was accepted for publication, and there weren’t any poems sitting on the side that didn’t make it in. In this way, the collection feels untrammeled with to me. Messy, yet pure. A poem about my childhood was removed from the collection at the request of my editors. It was about my mother being an all-star babysitter, wiping the dirt off the face of impoverished children in small-town Iowa. Sentimental stuff, and the editors didn’t care for it, for whatever reason. So, it got nixed. (Perhaps because it was the only poem that was retrospective.)

Honestly, thinking about my distant past just bores me. Growing up in a tiny town in a rural state, I never felt fully embraced by my peers or safely embodied. In a high school of 600 people, I was one of two minority students. And not because of any particular incidents—it was simply an atmospheric vibe, like humidity. When I left shortly after undergrad, I knew it was a place where I would never return to beyond short visits to my relatives—who I adore—mostly for funerals and weddings. Colorado is home—piercing skies, cranky mountains, and a chosen family of non-blood allies.

Yet so much of living in Colorado has allowed me to dilate my sense of time. Where I live—just to the east of the continental divide, along the Foothills of the Rocky Mountains in a high alpine desert—was once a seafloor roamed by dinosaurs. At the local monastery, the meditation instructor asks the students to consider what the experience of phenomena is like pre-cognition. (I.e., what is the thing itself before being cast through the prism of the brain and its conceptualization.) Backpacking beyond civilizations and sleeping under a bed of stars where the Milky Way does look like frothed whole milk is another expansion. And Zen Master Dogen, in his masterwork the Shobogenzo (The Treasury of the True Dharma Eye), asserts that each day is made of precisely 6,400,099,980 moments. I think all of these ways of knowing—from the extraordinarily granular to the cosmic—found their way into my collection.

While these poems can’t stop time, they do play with time. They enact. They elegize. They pledge to respect the ways in which we are caught up in time together. They are as much ancestors to the future as dreams pushed forward from the past. In short, the ways we fall down and reckon and complicate each other’s lives. On that note, you write in an early poem, “Meep Meep”: “We drink sand: // our delusions sustain us as we speed down the unmarked highway / toward an improvised vanishing point. We never get entirely away.” There are many moments in this collection where the speaker acknowledges being trapped both in time and circumstance.

Yet there are so many gorgeous poems in this collection where mercy bleeds through. I’m thinking, here, of your wife Sara helping you to unclasp her bra. Or contemplating having a child. Or watching archival video of Pina Bausch dancing along a tree-lined road. I found myself connecting deeply to the internal tension of your collection that navigates the membrane between unadorned harshness and intimacy. Between frustration and awakened embodiment. Cosmic distance and sacred friendships.

In your poem “Time of Asters” you talk about looking away from poll numbers to enjoy the “blueflame spokes” of flowers. Because we are approaching the end of the worst part of the pandemic (hopefully), are there any “mercies” you are looking forward to now that the world is beginning to approach something resembling pre-pandemic life? What’s keeping you sane these days, making the list of current mercies in your life?

Second, I’m noticing evidence on work—or the tools one often uses for work—prominently in this collection. I’m thinking of the hardhats, pickaxe and shovel that make their way into your poem “Clean Slate.” Or the ax in “Bunyan.” You’ve said that you scrambled to secure work during your various moves as Sara moved between academic positions. Were any of those jobs manual labor? As an independent contractor myself, I’m curious how these tools found their way into this collection.

Last, having read all three of your published collections, I can verify that while there is something fundamentally Landry-esque about each of your collections—a thread of brilliance interwoven that operates at the level of the line—your sense of independence from book to book is quite wonderful. Each feels discreet. I just have no idea what your next collection will look like; how it will be a departure from the previous offerings. This excites. Are you currently working on a new collection, and if so, is there anything you’d like to say about what we can expect from you next, or what you’re working on?

Ah, friend. Most of the manual labor I have been doing lately has been in service of fixing up a nonagenarian house. I dug a curtain drain around the whole thing and broke my foot in the

process. Wiring, reframing, cedar shingling, drywalling, amateur carpentry, concrete cutting, you name it.

In terms of mercies, I am looking forward to seeing what comes up in the garden beds. I am looking forward to readings and concerts on the grass. I am looking forward to getting my kid in the water and doing goofy cannonballs. And I have a lifelong friend whom I have been trying to connect with on a fly-fishing tutorial for the longest time: it looks like that finally might happen this summer. Honestly, our whole family is looking forward to school returning to normalcy in the foreseeable future. We have been homeschooling, but our kid needs other kids. And I miss teaching my courses in-person. It’s funny, when pandemic limitations really set in, I thought about all the travel I wanted to do when it became possible once again. But now I just want the little things: reliable schedules, hopefully seeing the bottom halves of peoples’ faces again someday. I hope the bookstores and museums I love weather this time. I want to see distant family again.

I have two collections in the works: one in conversation with Walter Benjamin and another centered on the loss of North American bats due to White-Nose Syndrome. I hope they see the light of day. How about you: What is up Kevin Phan’s sleeve?

I look forward to reading both of the collections you have in the works. And anything else you come up with in the future. Encountering your work in grad school was among my greatest pleasures at the U of M.

As for me, I’m working on a children’s book for adults titled Whales in Space. There’s also my grad school thesis. Nearly all of those poems have been published, so the manuscript just needs a home. And I’m working on a series of list poems that are lighthearted and surreal.

Whales in Space! Aren’t whales just the best? They are so intelligent. I like to imagine some of their songs translating as, “Gosh, those land-walkers really don’t know what the hell they are doing, do they?” I can’t wait to see this—and your other projects—come to fruition, Kevin.

Benjamin Landry is the author of Mercies in the American Desert (LSU), Burn Lyrics (Spuyten Duyvil) and Particle and Wave (Chicago). He received the Mina Shaughnessy Scholarship in Writing from the Bread Loaf School of English, where he earned his MA in English; and the Meijer Post-MFA Fellowship from the University of Michigan, where he earned his MFA in poetry. He has been nominated twice for a Pushcart Prize and received an Ohio Arts Council Individual Excellence Award for his poetry, which has appeared in venues such as The Kenyon Review, The New Yorker, Ploughshares and Poetry Daily. He is the guest poetry editor for Saranac Review.

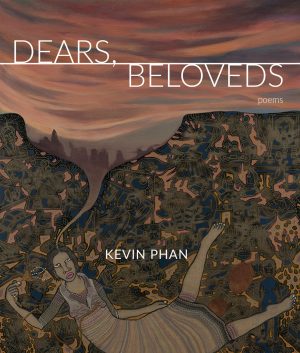

Kevin Phan is a Vietnamese-American graduate of the University of Michigan with an M.F.A. in Creative Writing in 2013 & from the University of Iowa with a B.A. in English Literature in 2005. He is a former Helen Zell Writers’ Program Postgraduate Fellow at the University of Michigan, where he won the Theodore Roethke & Bain-Swiggett Poetry Prizes. His work has been featured in Columbia Review, Poetry Northwest, Georgia Review, Fence, Pleiades, Gulf Coast, Colorado Review & elsewhere. His first collection of poetry, Dears, Beloveds, was published in the Fall of 2020 through the Center for Literary Publishing at Colorado State University.

This post may contain affiliate links.