After the death of her younger brother from sickle-cell anemia, twenty-year-old Akúa can’t understand why her older sister, back in Jamaica, doesn’t make the journey to Canada for his funeral. Instead, Akúa carries his ashes back to Kingston, along with big questions that defy neat answers: Why didn’t you stay with me? Why didn’t you come? Am I Jamaican?

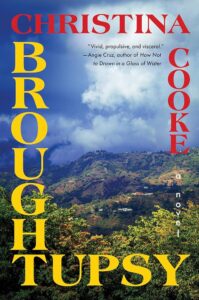

Christina Cooke’s big-hearted debut novel, Broughtupsy, captivated me with its emotional immediacy, luscious descriptions, and unrestrained embrace of all the fraught complexity of sibling relationships. Also, the book is funny. As she sees childhood landscapes anew, redevelops her ear for Jamaican patois, and follows sizzling smells through the markets, Akúa’s longing for reconnection with her sister and her home country often leads to friction. At the same time, she finds new connections—such as with a new love, Jayda—and she begins to more clearly see and more fiercely protect her own contours of self.

Christina and I first met in our MFA program, and we reconnected over video chat to talk about Broughtupsy. We discussed sibling birth order, faltering pathways toward identity formation, and what Christina learned over her novel’s thirteen-year journey to publication.

Alex Madison: This book is threaded with evocative descriptions, and I felt the prose especially take flight in descriptions of place and everything that attaches to place—weather, food, language. Your narrator, Akúa, left Jamaica with her father and brother when she was ten, first settling with her family in Texas and later making a home in Canada. Would you mind describing your own relationship with the places in this book?

Christina Cooke: Like Akúa, I am from Jamaica (though I never lived in Kingston, where the novel’s present action is set). Like her, I also lived in Texas and am now a citizen of Canada. To take the similarities one step further, she and I are both queer—which begs the question: is Broughtupsy a fictionalized record of my own upbringing?

No—but sorta yes. Let me explain.

Broughtupsy is not a record of the facts of my life. I do not have a little brother, much less one that’s dead. My mother is very much alive; I can feel my phone buzzing, so I think she might be texting me right now. And I do not have an older sister who separated from our family to stay behind in Jamaica. That is all fiction. I made that shit up.

But in many ways, Broughtupsy is a record of the emotional realities I’ve faced—the twists in consciousness, the turns in maturation as I settled into myself and came to terms with who I am. Writing this book was an exercise in cathartic release—an opportunity to consider, “Well, what did all that difficulty mean?” Through the ventriloquist act of fiction, I could finally admit to the parts of myself and my situation that I was too nervous or scared or ashamed to see.

It’s interesting that the journey of the novel created a parallel channel for processing your own psychical journey, too. I know that you wrote Broughtupsy over a long period of time, and since I see some coming-of-age elements in Akúa’s story, I wonder what it felt like to spend so many years with her across your own early adulthood. Did you feel yourself growing up alongside her, too?

Absolutely, yes. All told, I’ve been working on Broughtupsy for thirteen years—which includes two years where I didn’t write a single word and four years spent endeavoring toward publication. I used to look back on that long span of efforting and feel a twinge of shame. Why did it take so long? What’s wrong with you? Now, I’ve come to realize that thirteen years was exactly the right amount of time, and there’s simply no way Broughtupsy could’ve come together any faster than it did.

I was twenty-two when I started writing Akúa’s childhood and teenage years. Those sections have a palpable sense of visceral urgency—where we can really see, feel, and taste everything that animates Akúa’s world—because, quite frankly, I was fresh off of experiencing similar things myself. I could still access those tactile details, all those affecting turns in consciousness, and render them as immersive scenes on the page.

But it wasn’t until I passed thirty that I started to understand how to string those scenes together, how to shape them into a compelling story. I needed to mature to a place where I could access a level of remove and see the whole forest, rather than standing with my nose against the trees. I needed to develop my eye, my perspective, my craft as a writer in order to understand how to create an alluring container through which Akúa’s experiences could travel.

Broughtupsy needed a writer who could access the visceral urgency of Akúa’s process of becoming, as well as a writer standing at a discerning distance to enable the ordering of her narrative. Those are two very, very different people. Through the span of writing this book, I was both.

While reading this book, I thought of that oft-repeated idea about siblings—I’m not sure if there’s a single attribution, but I’m thinking of the idea that “No two children grow up in the same family” or “No two children have the same parents” because of their different ages. That seemed absolutely true in this family: all three siblings experience completely different lives, and that distance is part of what prevents Akúa and Tamika from accessing one another.

There’s a particularly poignant scene in which Akúa asks Tamika what their mother was like before she became sick with sickle cell anemia, and Tamika can’t adequately convey all of her mother to Akúa— saying instead, “She just was.” How were you thinking about those discordant sibling experiences throughout this novel?

I’m the last-born of three girls. In other words, I was born into a “we.” We were the Cooke girls, the Cooke sisters; we were a packaged deal, which is radically different from my eldest sister’s earliest experiences. There are nine years between her and myself, which is basically a generation. For her, when she was born, she was an “I.” It was just her for five years, hanging out by herself, then all of a sudden my middle sister showed up and she was like, “Who the fuck are you? And what do you mean, ‘us’?” I’m really fascinated by that. Sibling order affects the psyche in ways we all don’t fully understand.

It’s no surprise, then, that the character I found most beguiling was Tamika, the oldest sister. I was obsessed with her because she was the one character I just couldn’t crack. It took a long time for me to arrive at a multi-layered understanding of Tamika, to make her a rounded and dynamic character on the page. Sometimes I wonder if there are echoes there of my own confoundment of what it’s like to be born into an “I.” Tamika made it very clear that she has her own starkly defined consciousness, a fiercely defended sense of self; she was just not at all interested in sharing it with me, or with anyone really.

That resonates with my experience of Tamika—she felt very real to me, but always out of reach. I admired how the novel resists a linear progression in Akúa and Tamika’s relationship, which forms the core of the narrative, with Akúa returning to Jamaica to reconcile with her sister. Their moments of connection don’t necessarily build in a familiar Hollywood-movie arc. The connection keeps crumbling, destabilized by new moments of alienation and distance, often as a result of Tamika’s coldness and homophobia. How did you think about narrative propulsion in terms of their intimacy?

It’s important to highlight here that in Broughtupsy, Akúa goes back to Jamaica not only to reconcile with her sister, but also to reconcile with her sense of self. She’s labeled “Jamaican” when she’s living abroad, then labeled “foreigner” when she goes back to Jamaica. The complexities of her sibling relationship with Tamika make it possible to toggle between these two identities—to see those moments of recognition and refusal with her sister, which echoes the push and pull of Akúa locating herself within what it means to be an immigrant.

So naturally, because so much of Akúa’s and Tamika’s tension hinges on this permeating feeling of unease, the central solve here isn’t for them to come together and say I’m sorry in a Hallmark moment of kumbaya. That only takes care of half of the equation; that wouldn’t be enough. The other half is Akúa reconciling with Akúa—which means she needs to wrangle with, in a real and harrowing way, the place she calls home. Enter Jayda, Akúa’s love interest. She represents the third factor of what Akúa’s striving for, of living in easy queerness on her home island. So when all three come together, the explosive vibrancy that erupts. . . Well, I’ll let the reader discover that for themselves.

How does Akúa’s relationship with language weave into your thinking about progression? I noticed she would experience moments of relief when she felt she was getting a handle on the Jamaican patois and feeling a sense of belonging on the level of language, but in the climactic scene in which she’s, to paraphrase what you said, put through the wringer by Jamaica, she’s shut out by language again—unable to understand what people are saying.

This is similar to the dynamic between Akúa and Tamika in which they experience moments of closeness, and then something happens and it all falls apart because there’s no actual foundation for the relationship beyond shared blood. It’s the same for Akúa and her sense of Jamaican-ness. That identity exists thanks to her birth certificate, but it’s become complicated due to her process of migration. Throughout the novel, I created little glimmering moments that reflect that reality—where she figures out one piece of Jamaica and thinks she’s seeing the whole picture, but she really isn’t. There are so many factors in establishing a sense of self. It’s not a one-and-done situation.

In drafting, did you feel yourself writing toward a specific category of evolution or illumination for Akúa?

There wasn’t any singular thing that I was writing towards so much as I was thinking of the whole package of her parts and what that entails. Akúa is like a Rubik’s cube—but rather than trying to get each side one color, I was trying to create a pattern where each side had some red, some yellow, some green. I was trying to bring her to a place where her cosmology of self would be notably shifted, but in ways that didn’t feel pat.

What I feared was making Broughtupsy feel overly moralistic, which is very easy to do when you’re dealing with questions of culture and belonging and displacement and homophobia. It’s easy to say, “These people are good, those people are bad, and that’s that.” But real life exists in the knotted gray space. My goal with Akúa was to make her someone who became comfortable with abandoning those two poles of neat definition—to make her a person who embraces the beautiful yet dizzying freedom of the in-between.

I don’t want to give away too much here, but I loved the way the novel posited two alternate versions of the baptism ritual. Akúa consents to be baptized in Tamika’s church, and for a moment during that scene, I thought, “Oh, she’s making space for herself in this container that wasn’t built for her.” But then that possibility crumbles. And then later in the book, there’s another version of a sort of more private, more authentic baptism. What energized you about those ritual experiences?

I really wanted to exfoliate the differences between religion and spirituality. Religion is an institution. It has laws. It has decrees. It is a man-made construct, and therefore its primary role is to meet the needs of the people who made it. Now, in some contexts, that’s really beautiful—such as in an African American context, in church. As Ayana Mathis famously said, “Church is where Black people go to cry.” And so there’s a way in which the institution can become a place of safety, but that happens only according to the intention of the people making or re-making it. It can also become a place of harm.

So in a way, religion can be beautiful, yes, but it is made by people; people are flawed; thus, religion is flawed and partial. Spirituality is not. And what is spirituality? Sure, it’s rooted in this idea of a higher being ordering our lives, but it also encompasses an idea of connection that goes beyond categories, a kind of joining that is holy and inspired and true. The two baptismal scenes in Broughtupsy get at this delineation. One is a hollow gesture, a performance Akúa partakes in for the sake of pleasing the people around her. The later baptism is an instance of two souls trying to divinely connect.

An interesting element of Akúa’s self-conception was how she acknowledged that her romantic relationship with her first love, Sara, was protective in a way because Sara’s whiteness meant Sara could never “undo” her. In going to Jamaica and becoming involved with Jayda, then, Akúa is exposing herself in a new way; she’s making herself someone who can be undone by love. How were you thinking about this element of Akúa’s journey?

Honestly, I think the fact of Akúa’s first girlfriend being white is something a lot of queers of color can relate to, because homosexuality is often so fraught and taboo in our home cultures. There’s this journey that invariably happens where in order to come to an awareness of oneself as a queer body, people end up traversing into whiteness because if there are any safe spaces near them, they tend to be white. I’m so thrilled that now there are more spaces created by and for queer people of color, but we have to also recognize that those spaces mostly exist in cities. So if you’re not in a city, then that one gay bar in your small town is probably owned by a white person.

This process of sexual discovery then cultural remaking can look and feel a bit like like a boomerang: leaving the family and home culture in order to figure out what sexuality means to each of us—but inevitably, there comes a point where we realize, “Wait, I’m having to choose one part of who I am over the other. And also, y’all are racist as hell.” So we traverse back into our home cultures, bringing our whole, queer selves with us—and bracing for the inevitable turbulence that will accompany our landing.

Engaging in white queer spaces as a Black woman can come with a certain kind of freedom, because white space releases the pressure of the question, “Who am I as an immigrant?” You don’t have to reckon with yourself because you don’t see other Black people, other ciphers who will reflect that question back, which can feel like a real reprieve. If you’re not careful, you might start to mistake it as a sort of safety, as Akúa does. At most, it is as real as the shade from a passing cloud.

Are there aspects of the book we haven’t yet touched on that you’re especially hoping readers notice and connect with?

One thing I hope people notice—and this is not a thing that I expect everyone to react to; this is a very specific aspiration that has to do with how Jamaican readers engage with Broughtupsy—is the throughline of Ms. Lou and her cultural significance. Specifically, the queering of her cultural folklore to expand our understanding of who or what is Jamaican.

For brief context: Ms. Lou is one of the great cultural ambassadors of Jamaica because she was one of the first major figures who insisted on Jamaican patois as integral to our literary heritage. She fiercely defended the ever-shifting pastiche of West African and British influences that makes up Jamaican culture, and vehemently denounced this idea of choosing one or the other as representative of a “true” Jamaican. The middle ground is what makes us, in her mind. The in-between is what makes Jamaica possible.

Broughtupsy complicates Miss Lou’s idea and takes it one step further—by showing that if someone is Jamaican and queer, you are the rich overlap in the Venn diagram; you are in fertile middle ground. Akúa’s queerness further speaks to her Jamaicanness, instead of detracting from it. I hope that Jamaican readers really see that.

Speaking of readers’ reactions, you mentioned earlier that your solitary, or at least pre-reader version of this book, from first drafting to publication, spanned thirteen years. How does it feel now to have released it into the world?

You know, there were times earlier in this process when I felt free of the book—like when I handed it over to my agent to submit to publishing houses—and I relished those moments. At that point, I felt a lightness, a release; whatever happens, happens. But I will tell you that, once it sold and was actually no longer in my hands, it was weird. Because the truth is, this book has been one of the strongest constants in my life. It was with me for the two years of my first Master’s in Fredericton, then when I moved from Fredericton to Vancouver and spent two years doing social work, then Vancouver to Iowa for my MFA, from Iowa to Chicago as an adjunct professor, then finally Chicago to New York City, where I now work in development and fundraising. It’s been the throughline through multiple relationships and now into marriage. For thirteen years, it was the soundtrack of my life.

Up until publication, my attitude toward the book was, “I want you gone.” But once it was actually gone, I had a weird crisis of identity. I sold the book exactly two years ago—February 2022. So I’ve had a lot of time to just sit in my feelings. I didn’t realize that so much of how I defined my daily living was through writing this book.

The home it finally found was with Catapult—a smaller press that puts out incredible stuff, some of my favorite books over the past several years. What has your experience been like with them? How have you liked the smaller press world?

So far, I’ve loved Catapult. My editorial experience with them has been fantastic. My editor is Alicia Kroell (they/them), and what I really enjoy about them is that they’re hella white from some tiny-ass town called North Plains in Oregon, basically grew up in the woods, I mean for God’s sake they’re vegan, truly cannot be whiter—but they’re aware of that. And what I especially appreciate is that they don’t go around trying to overcompensate for their whiteness with the writers they work with who are of color.

Throughout the editorial process, they always lead with questions. If there was a section in Broughtupsy that seemed vague or unclear to them, their line of questioning was always, “Is it unclear to me because I’m not Jamaican? Or is it unclear because it’s unclear? If it’s because I’m just not inside the joke, then leave it, please. But think on this passage. Because if there isn’t a specific cultural reference you’re making here, then I think this is somewhere we should dig in.” I appreciated that curiosity-driven guidance.

Apart from the editorial experience, I just really appreciate Catapult’s ethos as a house, which is, “We’re not just trying to push this book to make money; we’re trying to launch you as an author.” The way they go about publicity and marketing is in service of sales, for sure, but their work also feels intended to further me as a thinker and writer by building a broad platform, which I so appreciate.

I’ve also found that I like being in an indie space. There’s much more willingness to experiment here. There’s a lot more expansive thinking. Honestly, what I’ve treasured most is that I’m with a house that understands my project and champions it on its own terms. Here I am with Catapult, a relatively tiny imprint, which would seemingly dictate that Broughtupsy would have a tiny impact—and yet I’m on over nineteen “most anticipated” lists.

Something I’ve loved watching on social media is your joy and excitement about the book release. I feel like many debut writers dream of this, but once it comes, they’re so overwhelmed by the anxiety and feeling of exposure that they can’t enjoy it. It seems you’re holding space for joy about this dream coming true and finding ways to celebrate it.

You know, my novel was rejected seventy-two times before finding my “yes.” Seventy-two editors who all told me to kindly go away. Do I think they all made the wrong call? Obviously. Nonetheless, did it leave me demoralized and utterly convinced that bookshelves could never make space for a work like mine? Big sigh.

But here’s the thing—and I can’t stress this enough to any aspiring writers reading this—it’s important to recognize that these editors are just people with their own personal taste and a discrete set of capabilities that may not always match up with the project that lands on their desk. After receiving rejection after rejection, it’s really easy to feel like, “Oh, the industry is not interested in my type of story.” It gladdens me to say I don’t think that’s completely true anymore. It is still the case that the majority of what’s allowed past the industry’s gatekeepers are predominantly white and male and American and straight, but there are editors and houses out there that are interested and committed to doing something else. You just need to find them when your work is ready to meet what they are able to do.

The upside to having two years between Broughtupsy’s sale and its publication is that I had the time and space to become excited about the book belonging to other people. So the way that I feel now is that I’ve created a wonderful kind of artifact, a record of my creative possibility that might reverberate around the world. It’s not mine anymore, and honestly, I love that for me. I can’t wait to witness the next phase of Broughtupsy’s life as it takes on resonance and meaning with readers near and far.

Alex Madison is a fiction writer based in Seattle. She interviews authors for Bookforum, The Millions, and elsewhere.

This post may contain affiliate links.