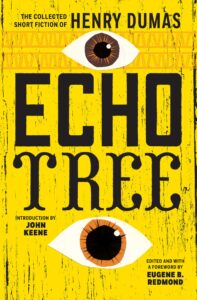

[Coffee House Press; 2021]

Reckoning with the legacy of Henry Dumas and his work as represented by Echo Tree, his collected short fiction now reissued by Coffee House Press, is an inherently fraught exercise. To begin with, the volume itself, while immensely valuable in keeping that legacy visible, does little to help us place Dumas’s work in the context of his life, tragically short as it turned out to be, or trace the development of his fiction, however abbreviated. Although it is evident enough in reading the stories themselves that they fall into two broad categories — stories set in the rural South (mostly his native Arkansas) and those set in the Harlem of the 1960s — it would still be useful to know more about his moves from one group to the other, whether his shift to the second category reflects a shift in Dumas’s political consciousness, whether he considered the one setting complementary to the other, etc. For this reissue, Coffee House does now include an introduction by John Keene, but its focus is largely biographical, and Keene provides just a general description of Dumas’s stories and their themes, which (understandably enough) Keene links to recent events associated with the Black Lives Matter movement.

Certainly Dumas seems especially pertinent to the current cultural and political moment, although this is due less to the fiction and more to the circumstances of his own life and death. Only a few of the stories in Echo Tree were actually published in Dumas’s lifetime, which was violently cut short in 1968, soon after the assassination of Martin Luther King, when he was no doubt murdered by a New York City policeman — the qualifier being necessary here because the incident remains murky in its particulars, and not even the police department’s own conclusion about the case can precisely be known (other than that no action was taken against the police officer) because its records of the case were destroyed 25 years ago. Allegedly, the police officer who shot Dumas later called it the result of “mistaken identity,” although the only extant contemporaneous report on the shooting (in the Amsterdam News) has it that the officer claimed Dumas threatened him with a knife. Of course, that Dumas was the victim of a racist-inflected cop killing is the most plausible explanation of whatever mystery still surrounds the incident, but to think of him most immediately as a previous victim of the systematic racism of American law enforcement risks overshadowing his considerable achievement as a writer, which has already been dimmed by the passage of time and the relative obscurity within the larger literary community in which his fiction has languished for too much of that time.

Additionally, the nature of that achievement might be further misunderstood. Keene in his introduction compares Dumas’s fiction to the work of Ishmael Reed, William Melvin Kelley, and Charles Wright, but also insightfully distinguishes it from the fiction of these contemporaries in its attempt to “expand the genre’s possibilities by incorporating speculative modes and elements of the fantastic,” drawing “from a range of traditions, including realist, gothic, horror and supernatural fiction,” as well as “African and African-American spirituality, folklore, and myths.” Although the fabulative qualities Keene describes are perhaps most evident in the “country” stories, even those set in urban spaces can display elements of the uncanny. None of Dumas’s stories follow customary narrative patterns. They often feature episodes of terror and violence, but few of them seem constructed to melodramatically highlight such episodes as the “climax” of a conventional story. Dumas’s fiction can take us to unexpected places, even when it doesn’t necessarily seem to be leading anywhere in particular at all (or should be taking us somewhere else).

Since the stories in Echo Tree do not seem to be organized into those that were published and those left unpublished (presumably there are a significant number of the latter), or assigned a spot in Dumas’s all-too-brief career, it is altogether possible that some of the effect of open-endedness or drift in the stories results from works that were incomplete or that might have ultimately become parts of a finally unrealized whole. While this unavoidably gives us a possibly distorted view of Dumas’s aesthetic intentions, it is clear enough that he was not much interested in satisfying the presumptions of readers (predominantly white) expecting a certain kind of social realism (a trait he certainly shared with Kelley and Reed), more inclined to treat “racial prejudice” not as a “problem” to be solved but as a built-in feature of American society that African-Americans have long had to accept as an unavoidable obstacle to their own agency and well-being. Dumas is frequently linked to the Afrofuturism of an artist such as Sun Ra, to whom he pays tribute in “The Metagenesis of Sunra,” although as this piece itself shows in its atypically fanciful style, Dumas’s fiction is generally more subdued, less deliberately extravagant.

The first (and probably Dumas’s most well-known) story in Echo Tree, “Ark of Bones,” is perhaps the most explicitly fantastic, although it is a fantasy of the most sobering and funereal kind. It could be called a tale of the supernatural: Two boys, Headeye and Fishbone, find themselves down by the riverbank when on the river itself suddenly appears a ghost ship. The boys make their way to the ship (taken by two mysterious strangers in a rowboat), where they find a large collection of bones and a crew tending them. “The under side of the whole ark was nothing but a great bonehouse,” Fishbone tells us:

I looked and saw crews of black men handlin in them bones. There was a crew of two or three under every cabin around that ark. Why, there must have been a million cabins. They were doin it very carefully, like they were holdin onto babies or something precious.

Although the boys return to shore (where they learn that a black man has recently been lynched and his body thrown into the river), a few days later Headeye informs the narrator he is leaving, presumably to return to the ship and rejoin the crews in their mission of sanctifying the bones.

It is not difficult to see how Dumas’s work could come to the attention of Toni Morrison, who may have been the first literary figure (she was an editor at the time) to “rediscover” Dumas a few years after his death. Surely the future author of Beloved would have considered Dumas’s story to be evoking the same sort of folklore-influenced magical realism characterizing that novel. But while “Ark of Bones” is certainly one of Dumas’s more notable achievements, it isn’t really quite representative of the stories in Echo Tree, at least in its form and narrative strategy. (In its depiction of the legacy of white supremacy for rural Southern Black Americans it is entirely representative.) The stories that incorporate the preternatural or the uncanny generally do so in a more stealthy and muted way, and some of the stories are more or less straightforwardly realistic, if not necessarily driven by plot. The title story depicts a belief in “spirit-talk” between two young boys, as one of them attempts to conjure up this spirit, but ultimately what ghostly activity that does occur (strange sounds in the woods) could still be attributed to the boys’ heightened sensitivity rather than to the supernatural.

Another story that flirts (maybe more than a flirtation) with the fantastic is “Fon,” one of a handful of the Southern stories that depicts encounters with white people, encounters that are tacitly threatening, when they don’t inevitably lead to acts of racial terrorism. In this story, a white man named Nillmon is in his car when a big rock suddenly breaks through his rear window. After tracking down a black youth, Nillmon decides that the youth, who identifies himself as Fon (short for Alfonso), is indeed the culprit and determines to “break” him, which he attempts to do after rounding up three other men to join in on the effort. Before they are able to kill Alfonso, however, all four of the men are struck down by arrows, fired from somewhere in the trees (or the sky). Fon, it would seem, is the herald of avenging spirits, emerging from the land (or descending from the heavens), who will eventually secure justice.

Justice is less clearly on the horizon in the other rural stories featuring confrontations with whites (“peckerwoods,” as Dumas’s characters are wont to call them). In “Rope of Wind,” a boy named Johnny B witnesses three nightriding white men kill a black minister and drag his body, tied in a sack to the back of their car, around the countryside. When the men go into a house, Johnny B manages to remove the body from the sack, but all he can do is hide the body in the woods and run the ten miles back home, “as if behind him flowed a river of blood and tears, like a phantom in the nite, black Johnny B, the running spirit, breaking the silence of the nite with his breathing, the only sound that kept his feet pounding the road, running, running, and running.”

“Rope of Wind” is a realist story, but the situation in which the protagonist finds himself is allegorized more explicitly in “Devil-Bird.” In this story a young boy, who is also the narrator, watches as his father ushers into their apartment an elegant gentleman who turns out to be Satan himself. A little later, another man, God, it would seem (dressed more shabbily than the Devil), also arrives, and God and Satan proceed to play a card game with the narrator’s parents, the winner to be given charge of the soul of the boy’s dying grandfather. Johnny B was himself indeed witness as well to the work of Satan, in the actions of the white men on the rampage. In many of Dumas’s stories, young black men and boys come to a recognition (whether they are aware of it or not) of, if not the dominion of evil, then the brutal and baffling realities of the world they are otherwise compelled to inhabit. The final story in Echo Tree, “Riot or Revolt,” modifies this version of the coming-of-age trope: A boy in Harlem observes the scenes in and around a local bookstore, a hub for the community, during a series of demonstrations. (The bookstore is visited by the Governor and the Mayor because “leaders are known to come here.”) What the boy sees is clearly inspiring to him, and in the story’s conclusion he joyously starts marching in an ongoing demonstration himself.

This story, as are many of the Harlem-based stories, is more a work of conventional realism than most of the stories set in the rural South, presumably an attempt to record the rising resistance and resolve among African-Americans making itself felt at the time of Dumas’s death. Yet some of the Southern stories are also essentially slices-of-life realism, and some of the Harlem stories incorporate fantasy. Others, such as “The Lake” and “The Metagenesis of Sunra,” are fantastic but use neither of these settings. Some stories do not conform easily to a perception of Dumas as either a fabulist or a realist, although these are the twin poles between which the fictions in Echo Tree vary. Such variety, however, is part of what makes the book a charged reading experience. It surely does underscore Dumas’s talent as a writer of fiction, although at the same time reminding us that he was so barbarously prevented from fully harvesting that talent.

Daniel Green is a literary critic whose essays and reviews have appeared in a variety of publications, both online and in print. His book of essays, Beyond the Blurb, has been published by Cow Eye Press and his website can be found at: http://noggs.typepad.com.

This post may contain affiliate links.