This piece was originally published in Full Stop Reviews Supplement #6. You can purchase the issue here or subscribe at our Patreon page.

The following is an excerpt from The Deep End: The Literary Scene in the Great Depression and Today by Jason Boog (OR Books; 2020), published with permission of OR Books.

•

In 2008, the journalist Mark I. Pinsky wrote an essay for The New Republic calling for a new federal writer’s project to save thousands of journalists from losing their jobs while print media crumbled. Pinsky had lost his job as a religion writer at the Orlando Sentinel in a humiliating round of layoffs. As internet prophets urged writers to embrace the chaotic economy of the web, Pinsky argued that a fundamental economic shift had occurred. He dared to state the truth: Writers needed help.

Millions of Americans keep detailed records of their lives on Facebook pages, on their Twitter feeds, and in other online networks. In some way, everybody is a writer now. But we have fractured our national narrative into self-absorbed and ultimately incomprehensible fragments. Perhaps the job of the next writer’s project could be to curate this awe-inspiring mass of content, helping the country tell itself stories again. A new Federal Writers Project could work to make our digital legacy comprehensible for future readers; to both preserve our ephemeral online stories and to create a more cohesive narratives from the vast online repositories.

Pinsky offered these suggestions for putting out-of-work newspaper reporters back to work:

. . . the FWP could begin by documenting the ground-level impact of the Great Recession; chronicling the transition to a green economy; or capturing the experiences of the thousands of immigrants who are changing the American complexion. Like the original FWP, the new version would focus in particular on those segments of society largely ignored by commercial and even public media. At the same time, the multimedia fruits of this research would be open-sourced to all media, as well as to academics. As an example, oral history as a discipline has made great strides in the past 70 years, and with the development of video techniques, the forum of the Internet could make these multi-media interviews widely available to schools and scholars, as well as to average Americans.

Most of the people responded to the article with scathing criticism. One anonymous reader wrote: “I didn’t see him writing years ago to save the 8-track tape or dot matrix printers, and print media is equally as outdated. I hate to see people lose jobs, but that is life sometimes, and government is not a panacea.”

A reader named Jeff was particularly blunt:

Go and develop new skills that are in demand in the marketplace and get yourselves another job! The government already supports “artists” who can’t create a painting or sculpture that another person actually wants to buy. What a stupid thing that is and it should be stopped immediately. You don’t have any kind of “right” to a job in journalism and any kind of “right” to be paid to write a single word. Tough luck. Either get another job, or go live in your parents’ basement and start a blog where you can complain all day and night about how you can’t get a job writing.

I felt a swell of hope reading Pinsky’s essay in 2008. I could imagine president Obama setting up some new program. I could imagine a sturdy, tough, but powerful solution to our problems. I dreamed about working for the twenty-first-century WPA. The article no longer remains online, but it once stood as a monument to the wrath of amateur internet pundits and the blistering scorn waiting for anybody who suggests a bailout for anyone other than bankers. Even Pinsky’s peers knew it wouldn’t work. He told me in an email: “Other journalists found it intriguing, with zero chance of happening. A few right wing media cranks reacted predictably.”

We could never rally around clear economic interests. George W. Bush had left a legacy of unrestricted finance and military spending. We inherited a deregulated financial universe and nobody could build a WPA on that framework. The revolution never arrived in 2008. We limped away like wounded animals, suffering quietly in our caves.

Pinsky blamed middle class writers for this defeatism:

. . . in the 1930s journalists considered themselves a part of the working class, largely identified with the political left, and understood the power of collective action. In the post-Watergate era, journalists became white collar, college-educated, and middle class, often upper-middle class. They disdained collective action, and saw themselves as above politics and ideology. And so, they were unable to slow, and thus cushion, the inevitable decline of newspapers.

I, like many of my fellow writers, was part of this trend. We emerged from relatively privileged backgrounds and earned advanced degrees in writing. I studied English literature at the University of Michigan and my journalism career began with a New York University master’s degree. Several generations of journalists before me had entered the profession from high-powered universities. Even though most of our salaries placed us closer to the working class, it took many years for twenty-first-century journalists to fight for unions.

Poetry and literary writing are no different. While MFA programs and journalism schools have provided a living wage for many writers, they also raise the educational bar, driving kids to take on more loans. If writers have not identified with workers since Nixon, then we hardly have any hope of saving ourselves again with any sort of labor organization. The irony is that even though most of my peers have entered the profession from high-class places, we will never earn enough to join the upper middle class. Someday soon, the only remaining “working” writers could be people who can afford to support themselves through grants, other work, or an inheritance. Pinsky has grown more pessimistic since the grim winter of 2008: “Unlike the 1930s, when the economy improves, living wage jobs in journalism are not coming back anytime soon, if ever.”

“The Turmoil of the Present”

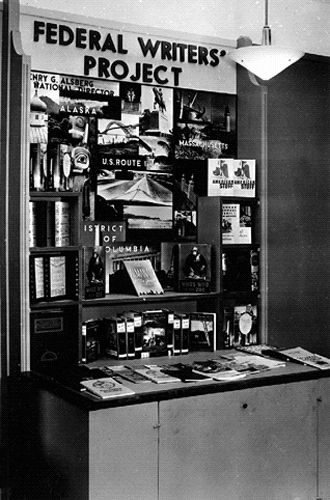

During my months working in the New York University Bobst Library, I found a dusty copy of The New York City Guide, a seventy-year-old book packed with maps, etchings, and strange stories about New York City. Orrick Johns was the first supervisor of the sprawling Federal Writers Project, leading one hundred and fifty writers as they collected material to include in the book. The guidebook opens with a sweeping stream-of-consciousness tour of Manhattan, a movie montage love poem for the city:

The morning sun picks out an apartment house, a cigar store, streams through the dusty windows of a loft. The racket swells with the light. These shoes are killing me, she said, taking the cover off the typewriter. Main Central is up to forty-six. Did you read about the earthquake? Looms, shears, jackhammers, trolley cars, voices, add to the din. And in the quieter streets the hawker with the pushcart moves slowly by. Badabadabada O Gee! Hawkers of vegetables, plants, fruit. Badabadabada O Gee! In half a million rooming-house rooms the call penetrates ill-fitting windows. The boy who came to be a writer is waked in his mid-town room and dresses for his shift on the elevator.

In 1936, things looked grim for the unfinished project. Franklin Roosevelt was gearing up for a rough election season as winter thawed, and the first critics of the Federal Writers Project emerged. Johns marshaled his scrappy but unfocused crew of writers to justify and protect the work they were doing.

During a period of clear-minded stability, Maxwell Bodenheim produced a magnificent essay about Greenwich Village. The essay paid homage to his glory days in the Village before World War I, when the Village was the birthplace of the bohemian movement: “In Greenwich Village the earliest rebels found comparative quiet, winding streets, houses with a flavor of the Old World, and cheap rents.” He described the often candle-lit meetings of Village intellectuals:

They talked of their work, of the arts, or of sex and Freud; and were secretly thrilled at doing so in mixed company. They discussed Socialism, the I.W.W., woman’s suffrage, and the philistinism of the folks back home. The conversation ranged from brilliant to silly, but always, instinctively or consciously, it was unconventional. And throughout, they drank endless glass es of tea for these were the days before Prohibition and bath-tub gin.

One hundred fifty writers had been toiling on the guidebook for months, but they had made little headway. As critics grumbled, the government sacked Samuel McCoy, the FWP supervisor above Johns, citing “insubordination and inefficiency.”

McCoy didn’t go quietly. In the papers, he blamed left wing conspiracies. The New York Times reported: “he said most of the employees were members of the writers’ union and the city project council and that they had been devoting most of their time and energy to factional activities against nonmembers.”

Other employees said the project was 90 percent populated by Communists and left wingers. The New York Times didn’t bother to check the facts. Johns struggled to keep control of his writers and resources during this poisonous period. But politics were certainly not the only problem. Nobody had quite figured out what these writers were supposed to do. They had been hired to write a guidebook about the city, to dig through archives, to research everything from zoos to shop girl strikes, to survey New Yorkers, to record city folklore, to do a thousand conflicting and impossible jobs.

Former FWP supervisor Jerre Mangione described these troubled years at the WPA: “They were psychologically incapable of planning for the future. Caught in the turmoil of the present, they lived from day to day in constant dread of losing their jobs and in mortal fear of the growing Nazi menace in Europe.” The “turmoil of the present” combined the crippling anxiety of economic downturns with a nagging sense of future dread and real-time worries. These are the feelings that keep workers trapped at dead-end jobs, that stop young families from buying houses, that stall efforts to unionize during turbulent times.

Despite his best efforts, even a simple pamphlet that Johns published about New York State could not satisfy Washington, DC. His supervisor chastised the poet for including lurid details about the city, copy “afflicted with the cheapest sort of ballyhoo . . . Lurid intimations of Chinatown dens, the come-on stuff of the tourist barkers.” The pamphlet generated scathing editorials in conservative newspapers around the city. The WPA was forced to issue an official apology in 1937.

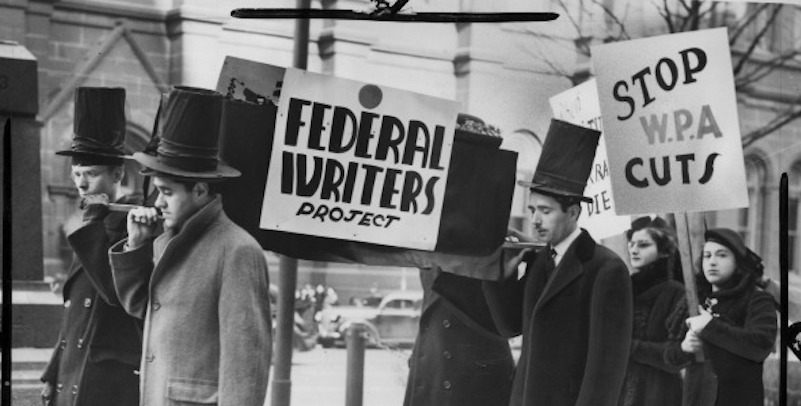

On August 22, 1936, the WPA fired three hundred New York City employees in a single swipe. The shocked workers refused to leave the WPA offices, mingling with another group of activists who were marching for better relief payments for the unemployed. The relief protestors carried around an empty baby-sized coffin, memorializing the three-year-old Jersey boy who starved to death after his family was dropped from the relief rolls. Don’t let this happen in New York, read their signs.

As the protests boiled over at WPA buildings around the city, Raven Poetry Circle member Marie Margaret Winthrop, who was also the secretary of the American Writers Association, hand-delivered an angry letter to Orrick Johns. The Association accused the FWP administrators of favoring Communists. They were specifically upset that Johns had hired a Daily Worker reporter to serve as his publicity officer.

I have a picture of Winthrop from the Raven Poetry Circle archives. Her hair is brushed back and the May sunshine illuminates her features. She has high cheekbones and a simple smile. She lounges against a park fence with the casual demur of a catalog model. She wears a long skirt, a leather jacket, and a white blouse with two or three buttons open. She clutches her notebook in one hand.

In her poem “White Roses,” she writes:

I’ve gone mad with the clatter of falling bric a brac Mad with the clash of wheels within wheels

The din of falling god is a tinny sound

Like the sickly color of pink

The sharp staccato shrillness of idols falling

And the falling of a million men, are the little sounds Almost drowned by

the noises of the rushing years. But I can hear them—

All the overtones and undertones

Of an insane symphony.

With her crazy imagery, her loose line, and her leather jacket, she anticipates the Beatniks as she describes the apocalypse. She has the most rhythm of all the Ravens. She channels the pop pop pop of new wave poetry, wiggling out of the tight constraints of formal verse.

In 1936, the director of the National Youth Administration outlined the size of the Crisis Generation in a New York Times essay, recording some grim statistics about American workers between sixteen- and twenty-four years old:

. . . more than one in seven are heads or members of relief families. Of the 600,000 who live in urban areas and are of school age, 300,000 are not in school and are not working or seeking work. Considerably more than half have had work experience, but three fourths of these are unskilled or semi-skilled, and only five percent of the whole unemployed group of young people consists of skilled workers.

In October, thirty-five unemployed writers showed up at Johns’s office to mount a hunger strike. They were more members of the American Writers Union who were struggling to be heard. Though the country seemed to be recovering from the Depression, they wanted to remind the world that many writers could not find work. They decided to sit and wait without eating until jobs were forthcoming.

Johns didn’t call the police. He let the demonstrators sit in his office during the whole futile hunger strike. There were no more jobs coming, but these demonstrations made headlines for days. The unemployed writers traded chairs with FWP writers throughout the workday. They were peaceful, but they set a powerful precedent. These writers would not wait for work or slink off into the shadows. However, the hunger strike only lasted all of twenty-six hours.

On account of the bad publicity, the WPA caved to their demands and granted Johns the ability to hire fifty more workers. They also began wondering about his control of the situation. Back in Washington, DC, other officials planned ways to kick the one-legged poet out. Nevertheless, these protests marked a turning point. On the surface, the country seemed to be recovering, but these protests made the truth of the situation very visible—making front-page headlines for several months straight.

Scorched-Earth Bookselling

Something happened during the Great Recession, something we seldom discuss as writers, as workers, or as citizens. We stumbled out of that dark time with a completely consolidated economy. We now live in a world ruled by monopoly, where everything from mayonnaise to airlines to publishing is in the control of a very small group of powerful companies. In January 2017, a young legal scholar named Lina M. Khan diagnosed our new condition in a paper in The Yale Law Journal called “Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox.” In 2019, I covered one of her keynote speeches at the PubWest conference in Santa Fe, New Mexico where her radical ideas about monopoly enforcement produced a long standing ovation from a roomful of booksellers.

The legal scholar described a “monopoly crisis” in the United States that arose after a fundamental shift in anti-trust enforcement in the 1980s. “More than any other firm, Amazon depicts how a company can come to monopolize all sorts of markets without triggering scrutiny under our anti-monopoly laws,” Khan said, detailing the online retailer’s “sheer dominance” of the publishing marketplace. “Amazon is seller of books, a publisher of books, a printer of books, and dominant in both the e-reader and e-book markets. It is both a third-party marketplace and a merchant of its own private labels, creating a huge conflict of interest,” she said. This unregulated landscape enabled the rise of our present corporate oligarchy, a government run by a clown who takes credit for a stock market that only enriches the wealthiest citizens and siphons resources straight from his working-class base.

We saw the powerful effects of monopoly when Borders declared bankruptcy in February 2011. Within days, two hundred stores were shuttered. The company briefly entertained hopes of a buyout bid or auction, but these deals also collapsed and so the company tumbled into liquidation. Borders Group President Mike Edwards posted his unhappy resignation: “We were all working hard towards a different outcome, but the headwinds we have been facing for quite some time, including the rapidly changing book industry, eReader revolution, and turbulent economy, have brought us to where we are now.”

Box stores like Borders changed the literary economy drastically, pushing the market toward consolidation and monopoly. Borders built a bookselling juggernaut in the mid-1990s by creating a revolutionary computer inventory system that could track a book’s popularity through changes in stock around the country. Bookselling moved from relying on human choices to computer-generated sales. Editor Paul Constant explained the transition in a brilliant essay about working on the Borders sales floor:

Our displays were bought and paid for by publishers; where we used to present books that we loved and wanted to champion, now mediocre crap was piled on every flat surface. The front of the store, with all the kitchen magnets and board games and junk you don’t need took over large chunks of the expansive magazine and local-interest sections. Orders came from the corporate headquarters in Ann Arbor every Sunday to change out the displays. One time I had to take down some of the store’s most exciting up-and-coming fiction titles (including a newly published book that was gathering word-of-mouth buzz, thanks to our booksellers, called Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone) to put up a wall of Clash CDs. One month, for some reason, the cafe sold Ernest Hemingway-branded chai.

In the 2000s, the department store mentality was triumphant. There was no union to protect Borders employees. There was nobody to stand up and fight as these jobs evaporated. When Borders closed for good in September 2011, the remaining 399 stores and 10,700 employees were out on their own.

Any dissent was stranded in online discussion boards and quick blog posts. Thousands of readers shared pictures of signs that read “we don’t have a bathroom, try Amazon” inside the closing stores. Gallows humor took the place of real anger. The debate was quickly framed in two ways in the media: Either a badly managed corporation had collapsed or else the eBook revolution had taken its first major victim. Our headlines focused on bookselling trends instead of on a floundering workforce at the mercy of brutal capitalist necessity.

Both these narratives excluded the fates, futures, and feelings of thousands of workers. Massive numbers of the newly jobless swamped the unemployment rolls in September. Nobody—from the publishing industry to the local government to federal arts societies—offered any official support for these unemployed workers. We failed our first major test as a collective literary community in this new recession. We never made national headlines fighting to replace or maintain these jobs. None of us were staging hunger strikes at Borders. The publisher and bookseller Dennis Johnson described on the MobyLives blog the new ecosystem:

Publishers are on a crash course learning how to survive without any volume booksellers, and in an environment with one retailer (oh, guess) representing as much of its business as—well, who knows? Eighty percent? More? That alone is likely to make publishers give up on printing books—there’s no sense in printing books if your main outlet isn’t going to order any until they sell them—and join the digital ‘revolution.’ In short, B&N’s scorched earth policy of the 1990s has ultimately left us with, well, scorched earth. If the book is going to survive it, it’s going to take some real revolutionary activity, indeed.

If Johnson’s prophecy comes true, big publishers will have no resources to support fledgling authors. Conglomerate publishers will continue to shave margins, pushing more midlist writers into the indie publishing scene. Writers’ collectives could ease the workload and streamline marketing. These writers could form stronger bands in this post-apocalyptic landscape. The landscape will be crowded with stranded writers: Sooty survivors will have to band together to survive.

Jason Boog is the West Coast correspondent for Publishers Weekly and was previously publishing editor at Mediabistro, leading the GalleyCat and AppNewser blogs. He is the author of Born Reading: Bringing Up Bookworms in a Digital Age. His journalism has appeared in The Believer, Salon, The Awl, NPR Books, and The Los Angeles Review of Books.

This post may contain affiliate links.