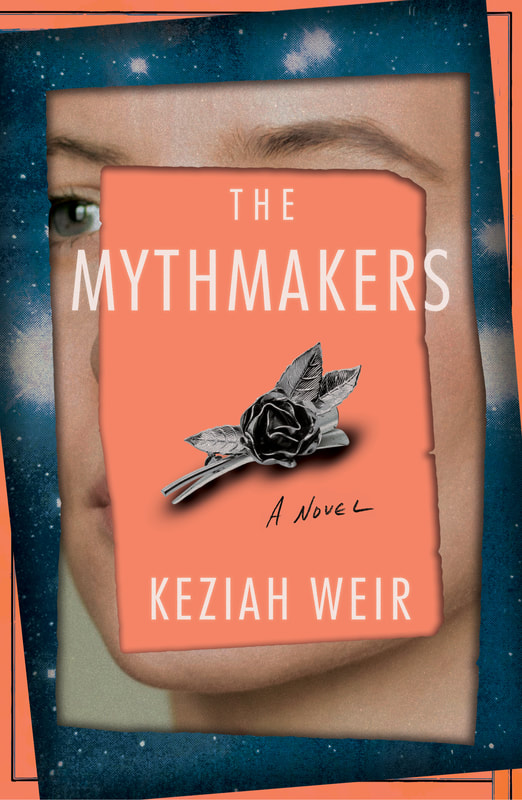

Keziah Weir’s nesting-doll of a debut novel, The Mythmakers, explores questions of art making, ownership, ambition, and how relationships shape a life. The book follows Sal, a twenty-something woman whose New York life as a journalist (and a girlfriend) is unraveling. When Sal meets an older male author at a literary event, she thinks nothing of it until she later comes across a depiction of herself and that very encounter in the last short story he had published before he died. This sets Sal off on a trip upstate to learn more about the story and the author, which, of course, is really an attempt to learn more about herself. Sal becomes immersed in the world of the women who shaped the author: his widow Moira, an astrophysicist who initially doesn’t want to get involved with Sal; his daughter Caroline, an aspiring musician whose father never understood her work; and a gleaming, wild woman from his past. The Mythmakers is an interrogation of the relationship between artist and muse, and feels like getting into a car without knowing where you’re going only to stop at the most beautiful destinations. Ultimately, The Mythmakers is an ode to women, art, and beauty.

Keziah and I actually went to Bard College together, although we sadly didn’t know each other very well at the time. After I read her novel, I sent some equal parts excited and unhinged DMs to her about her book, which she was very gracious about. I was delighted to find that she’s just as lovely, kind, and smart in real life as she is on the page. I spoke to her by phone about the gendered history of artist/muse, balancing life and art, when Philip Roth returned a set of kittens, and more.

Ariel Martinez: You’re a journalist in addition to a fiction writer. Something I struggle with in nonfiction is the morality of telling someone else’s story. Do you think that writing is an ethical dilemma?

Keziah Weir: I think that it is. Part of the reason that comes out in the book so much is I just have unanswered questions, or have this continuing curiosity or discomfort or anxiety, about being entrusted with other people’s stories and what it means to get it “right.” I really waffle back and forth, because a huge part of me believes that there’s no story that can’t be told and that there are objective facts that one can report. But then of course, we’re human beings and all kinds of other things come into play. Anyone who is at all sensitive or empathetic, you don’t want to devastate people with what you write about them. But then as a journalist you do have an obligation to report the truth. Those two things can come into conflict with each other. And you can’t predict what people are going to be bothered by. You can’t be writing about someone and thinking about how they’ll receive it. But I think as a person in the world it’s really hard not to have that in your mind.

I think it’s Maggie Nelson who said that writing is immoral.

Yeah! And Janet Malcolm and Joan Didion . . . So many people have pointed out that writers are vampires. And that’s all true, but there’s also so much good. Writing is really the most important thing to me so it’s really a weird little slackline to be balancing on.

You go so deep into the relationship between artist and muse and the layers and complications of that. Do you think that’s inherently a gendered dynamic?

I think there’s a long history of men turning their gaze onto women and portraying women in various art forms in a very specific way that often has similarities. This is visual art, but I remember someone did a study of all of the portraits at The Met and a huge percentage were by men of naked women. That’s a real thing and those are real numbers. There’s so much literature by men that has female muse characters in it, which was the historical context that I was steeped in. I was in a literature program that I graduated from in 2013. That was pre #MeToo, pre-certain consciousnesses about expanding the canon. It definitely influenced what I was reading at a very formative time.

What was the first kernel of the book?

I had been trying to write a book for a year and I had been sort of kicking things around. I had a general idea that there was going to be a relationship between a younger woman and an older woman. I don’t know when exactly Moira solidified but she was there pretty early on. But then I had this encounter at the New York Public Library. I went to a reading with one of my former Bard professors who was a fiction writer. It was a conversation between Karen Russell and Rivka Galchen. I love both of their writing. While I was there at the party I just felt so out of place; I was very young, I had no idea who anybody was, and then this older gentleman just started chatting with me by the drinks table. We talked for maybe an hour or maybe less and then he wandered off and my professor came up to me and was like, “Oh my gosh, did you know that was the man who wrote the screenplay for Blade Runner?” I had no idea, but he was very charismatic and very generous and very interested in me. And when you’re twenty-two, you just want people to be interested in you. That encounter kicked off the beginning of the book. And then I very quickly realized I didn’t want to be writing autofiction. And so after that initial encounter, everything diverged very wildly from my own experiences.

So he was your muse.

He was my muse! I was thinking I should send him a note and say thank you.

Oh my god, you absolutely should. Something that I also admired was the amount of science in the book, with Moira being an astrophysicist, and how you really distilled it into literary prose. How much research did you do and how did you get that into your own voice?

So much. I’ve always been interested in the metaphors and the beautiful storytelling of science in the way that Martin is interested in it in the book. There were about twelve books on early NASA history and textbooks on the universe and black holes . . . Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History of Time . . . I read those and then I cherry picked and took so many notes, and then when it came time to actually write them I didn’t look at any of the notes and just wrote what I remembered and then sort of fact checked myself. But I am also married to somebody who is very scientific. He’s a data scientist but he has a brain that can do that. His dad is actually a nuclear physicist. We were talking a lot about time, and he would say things and blow my mind in just a couple sentences. He’s the one who said, “Oh yeah if you could teleport yourself to a faraway star and look at earth, you’d actually be looking back in time.” That concept was just so incredible and gorgeous to me. That’s the little game that Moira plays with her daughter in the book.

What obstacles did you face that you didn’t anticipate?

I just did not know how to write a novel. It took me so long to figure out how to get past the first couple chapters and figure out how to be okay with not knowing exactly where I was going and just writing into an abyss and knowing things would get thrown out. I had only written short stories before this and it’s just a totally different juggling game. It felt like a physical battle to wrangle this number of words in one document. Just getting a first draft took years and years. And then everything after that wasn’t easy but felt more comfortable. And then just time . . . I had pretty time-consuming full-time jobs for the entirety of writing it. I was chipping away at it in one or two hour chunks in the mornings and then not hanging out with friends because I knew I needed to write. Those were the hardest things. It wasn’t even self doubt when writing, because I really didn’t think that anyone would ever read it. I didn’t tell a lot of people I was working on it so it felt protected in that way. The stakes were kind of low in a certain sense, but the stakes personally felt very high because every year that I hadn’t finished it felt like another depressing year that I hadn’t finished the book.

Do you feel relief now that it’s out?

Yeah, I think so. It just feels so surreal. I think it will probably sink in in a couple of months. I’m glad that it’s out and not just sitting in a drawer until the end of time.

Book stuff also just takes so long.

It does! And I think that in some ways was really helpful. It’s not like you ink the last period and then it comes out next week. There’s so much time between really properly finishing it and it coming out, so there’s time to adjust. The whole thing is very strange.

I was so captivated by all of the women in the book who were all so different. What aspects of femininity did you want to explore in each of them?

Writing the women was just so much fun. I really miss getting to be with them and getting to explore their lives. They all do feel so different to me. Caroline and Moira especially just feel so like their own people. I know that there are certain little bits of strangers or acquaintances that made their way into them, but they feel like they just came from the air. In terms of femininity, I think ambition and what it means to be ambitious and what it means to succeed or fail as a woman was interesting. And then the interpersonal relationships. I have many close female friendships and relationships with women who are not family but like family, and my relationship with my mom . . . All of those are such important parts of my life. Getting to explore those relationships but through different people felt really fun. I was also interested in female sexuality and desire and wanting to be seen and also not wanting to be looked at all the time. There are so many . . . nobody has asked about that so I haven’t really thought about it in a critical way but I think the whole book is about women.

Did I totally project that there’s some Bard in the book?

I mean definitely, it takes place in the vicinity. The town is not right on the Hudson, but that was definitely a write-what-you-know, and I know the Hudson Valley. At different points, there were various amounts of the college in the book. And now there’s almost nothing. I love reading campus novels, but I think that’s not really what this one was asking to be.

Sal has this combination of aimlessness and ambition that I think is very indicative of—at least my—twenties. How did you tap into that?

Sal was so interesting to write because on paper we share so many things, but she felt very different from me, especially as I got older as I was writing this. I think a lot of her metrics for success are not things she can really control. At the beginning, she just wants to be writing things that other people read, but she doesn’t really have a sense of what stories she wants to be telling. She wants to be telling stories that are actually about herself but through other people. She’s seeking out success stories that she can nab herself onto. And I think so much of growing up is just looking at other people who are doing things you wish you could be doing and wondering how they got there. But then of course you have to find your own place in that. And that’s a tricky thing to do.

You said earlier that you wanted to explore succeeding and failing as a woman: Do you think succeeding as a woman is possible?

I think so. I hope so. I think it really depends on what your measure of success is. I’m trying very hard to not look at Goodreads, but it is interesting to look at Goodreads and see that so many books written by women compel people to have really interesting reactions of real, visceral dislike for women narrators and women writers writing about “women things.” I can only really speak from my own experience, but we are in a generation that watched “Lean In” kind of fail, and that’s an interesting thing to grapple with. And to know that men ask for things and get things and are seen as powerful for certain character traits, but if those same character traits are mapped onto someone who’s a woman or not a white man, it’s received in a very different way. But I think, yes—I think you can be successful as a woman. But it does seem like there’s a lot of people who think that you can’t.

It’s interesting how likability has become this dominant metric—I think especially in books, maybe in movies—but I see it so much in books where people are like, “I couldn’t get through it, I didn’t like the narrator,” and it’s like, Maybe that’s the point, babe!

Completely. And I think with movies if the actress is really hot then she gets a pass and can be bad and not likable, but you don’t have that for books. Even if you say like, “She’s very beautiful but a real bitch,” people aren’t willing to go along with it in the same way as when there are these horrible narrators of these books about men just Bull-in-a-China-shop-ing through the world. We’re just like, yes, love that anti-hero.

I literally just saw on Instagram someone was like, “I can’t believe so many of you have read My Year of Relaxation, I hate that narrator!” And that narrator is so beautiful, it’s said again and again that she’s so beautiful, she’s so stunning but it doesn’t carry the same weight on the page. It’s so funny. Actually it’s not funny at all.

Yes, [sarcastically] so interesting ha-ha-ha!

What do you think of Jenny Offill’s concept of the art monster? How do you balance art and real life?

I think one of my big sadnesses—which comes from all kinds of things—is that you don’t get to be everything. You don’t get to have a committed relationship in an ongoing way and dip out of your life constantly to make art. You don’t get to have friends and write literally anything you want about all the people in your life with no consequences. I guess it’s like the Tár thing: Can you be a good person and a great artist? Yes, I think you can, and there are models of that. Toni Morrison gave herself so generously to so many people and was a mother and wrote literal genius texts. I interviewed Zadie Smith for Elle when I was there and it was great. I don’t remember what of this made it into the piece, and this is not a direct quote, but she was talking about how of course one gives up time to write if you become a parent, if you’re going to be the kind of parent who spends time with their children. But does that mean that you’re decreasing your writing? You’re enlarging your life in a lot of ways. Nobody can have everything. It’s just about making decisions. I am not an art monster. I have a dog who takes a lot of time to walk every day.

But that helps writing!

There’s this funny story . . . I don’t know how true it is, and he also wrote about it in fiction so I get it all confused, but I think that Philip Roth was given a kitten or a pair of kittens from a neighbor, and I think a character of his also had this happen. He either wrote about it or it happened to him or both. He became so entranced by these kittens that he didn’t write and just stared at them. He had to give them back because he felt like he would never write again. But that’s such an interesting, indicative little slice of what a person wants their life to be.

Ariél M. Martinez is a queer femme writer from San Antonio, Texas. She holds an MFA from Bennington College, is an editor at no tokens and runs the book recommendation substack all the things she said (were good) that focuses on queer and/or women authors. She lives in Brooklyn with two chihuahuas where she is working on a memoir about Britney Spears. Find her on social media @arielmtnz.

This post may contain affiliate links.