It‘s been nearly a year since the JWST first started relaying images back to Earth. So far those images have comprised newly discovered galaxies, higher quality snaps of known nebulas, and more detailed surveys of distant constellations, showing off between them the diverse capabilities of the JWST, which is a hundred times more powerful than the Hubble telescope. Heralded as “the premier observatory of the next decade,” the JWST interprets infrared wavelengths with the objective of peering back in time to the origins of the earliest stars and galaxies, and these images are proof that the optimism of the scientific community is not unwarranted. They are the first of what will potentially be a long line of photographs yielding key insights into the nature of exoplanets and the material composition of the universe. “Put together it’s a new window into the history of our universe,” remarked President Biden at the unveiling in July 2022. “Today we’re going to get a glimpse of the first light to shine through that window.”

Space enthusiasts are having their moment. If you’re not one of them, imagine, for a moment, that you are. Imagine your glee on the 12th of July as the image of SMACS 0723, a cluster of galaxies as vivid and brilliant as a black opal, was released to the public. Print it off and impale it on your pinboard, however, and you’ll soon struggle to evade comparison with the similarly vivid, arguably more exciting photos which already cover the cork. There, at the top left corner perhaps, is the first photograph of Earth from space (1959); and then behold, moving along, those brazen gods of war and love, Mars and Venus, images snatched from the first planetary flybys (1962); or the glimmering aquamarine that is the first confirmatory photo of an exoplanet (2004). Granted, the image of Carina Nebula is gorgeous, but against this backdrop it looks like little more than a knockoff of the Hubble’s “Pillars of Creation.” You sit back in your chair and heave a soft, nostalgic sigh, and then laugh a little at the irony of it all. For the truth is that nothing the JSWT discovers will top these pioneering images, whose beauty and importance reside in the fact that they foredoomed all that came after them to stand in their shadow.

This is an unconventional, somewhat cynical way of discussing space discovery, especially given that the unanimous jubilation surrounding the images is a phenomenon as rare as a habitable planet. But even the heavens ought not to be spared the inquisitions of the Devil’s advocate, and when the media has its hands full asking what is to be gained by the telescope’s discoveries, is it any less appropriate to ask what might be lost?

Commentators have sought to address this in quantitative terms, noting that close to $10 billion and decades of research would be effectively poured down the drain if the telescope were to suffer irreparable damage. But the telescope made it to its destination, the second Sun-Earth Lagrange point, with scarcely a hitch, and has remained intact ever since. Instead, what we are set to lose is something priceless and irretrievable, and whose decreasing prevalence in human society was laid bare by the abnormality of the reaction to the July images: that rare cocktail of wonder, excitement, and imagination that fuels our lust for exploration. Simply put, the more we discover about the universe, the more boring we seem to find it.

But it isn’t merely a case of “been there, done that.” The truth is, in poking ever further into space, we are actively smothering the infinite possibilities of the “could be” with the bland, cumbersome blanket of the “is.” Fortunately, if the gains from the JWST are relatively inconsequential as far as the non-scientist is concerned, then so too are the losses. The telescope’s primary function is to gaze into the past, which makes it somewhat unique in the catalogue of past and present space missions. As its name implies, however, the majority of space exploration deals not in time, but space.

Over the next decade NASA alone is expected to conduct eighty new space missions, eighteen of which will involve deep space exploration. This does not account for the Chinese Academy’s ambition to discover “Earth 2.0” or the dozens of commercial initiatives currently underway. Nor indeed does it account for NASA’s current expeditionary missions, which range from the Neowise telescope’s objective of imaging the entire sky in infrared, to the SOFIA’s (the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy) ambition to map the magnetic fields of galactic bones. Recent discoveries include a five-billion-year-old laser light in deep space and ice volcanoes on Pluto. For the rest, however, a quick look through NASA’s news tabs reveals a startling lack of “real” news. Most articles constitute little more than celebrations of space mission anniversaries or flashbacks to far older discoveries. If a damaged telescope can be considered a failure, then why not a successful space mission whose winnings amount to the same: nothing?

Beyond the fanfare surrounding the initial images, the JWST may under-deliver too. Its gains so far are relatively minor, after all. There are already 2,066 planetary systems known to us, their contents chemically diverse but otherwise of little scientific—or at least epistemological—interest, so it is unlikely that new ground will be broken in that domain. If the JWST fails to produce anything of consequence, the failure will be merely one in a long line of disappointments, at least from the point of view of anyone hoping for a revolutionary finding, no matter how much various space agencies have endeavored to portray them as unprecedented successes. This is particularly the case for generations who have grown up on a diet of wildly imaginative science fiction. One need only weigh up the success of the mapping of the bare, monochrome surface of Mars by Soviet probes in the 1970s, against the lush and colorful depictions of the Red Planet suddenly made impossible by it, as featured in C.S. Lewis’s The Space Trilogy for example, to note the scale of the disappointment; or the featureless surface images of Saturn produced by a NASA probe in 1980 against the Saturn of Voltaire’s Micromégas, host to a highly advanced species existing in perfect harmony. In each case the casualty has been the same: That otherness, the blank slate onto which we project our dreams, has been, if not erased, then pushed farther and farther away.

It may sound frivolous, but we can already see the effects of this entropy of the imagination in our society and culture. At first glance, science fiction seems in a healthy state. The success of recent blockbusters stands as testament to this interpretation. 2021’s Dune and last year’s Avatar: The Way of Water smashed expectations at the box office, grossing $4,000,000 and $2,300,000,000 respectively. Dune’s winnings do not reflect the profits from an additional two million HBO streams, so it’s fair to say it far outperformed David Lynch’s 1984 adaptation of the sci-fi classic (not to mention Jodorowsky’s aborted attempt to do the same, which would have featured an Emperor Shaddam IV with a toilet for a throne, the villainous Harkonnen army staging mass defecations, and a runtime of roughly fifteen hours). Naturally, critics lauded the 2021 film for capturing the spirit of the book better than any previous adaptation. But therein lies the problem. Villeneuve’s Dune may be the most successful expression of Frank Herbert’s vision yet, but that success is largely a Frankenstein of recycled nostalgia. By comparison, the new Avatar film may be a largely original production, but its success rides on the coattails of a fourteen-year-old prequel, and its message is singularly unambiguous by the subtle standards of modern-day Hollywood: that the future of space exploration will echo the history of colonial exploitation.

Other recent films, such as Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets, Guardians of the Galaxy, and the Star Trek movies are shaping our conversations about the future of humanity by looking squarely at the past: at the comic books and dime novels and black-and-white TV shows upon which they’re based, from a time before man had even stepped on the moon. Owing to high production costs, there are countless classics of sci-fi which have never made it to the big screen—Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness, for instance, or Alfred Bester’s The Stars My Destination—but these, too, were written before the idea of venturing into space became a reality rather than a mere dream. It is tempting to look back on the 50s, 60s, and 70s as Neil Armstrong must have viewed the face of the earth from the moon: a fruitful, colourful, vibrant world, in contrast with the comparatively drab age in which we seem to live.

If the solution to this imaginative drought is to be found in space, the problem lies partly in Hollywood. Capitalizing on existing fandoms and adapting established material without having to channel time, talent, and money into new IPs is a recipe for success, as the current explosion of sequels, remakes, and reboots bears witness. This goes some way to explaining why producers are loath to turn newer sci-fi stories into motion pictures.

But this is only part of the story. The fact is that science fiction is being written on a scale we’ve never seen before, becoming more diverse in perspective and representation, as well as tackling increasingly current societal issues such as climate change and AI. But despite this new cultural environment, you would be hard pressed to find a recent example that matches the scale and sheer spectacle of Dune. The highly imaginative fantasies of Robert Heinlein, Philip K. Dick, and Doris Lessing have given way to the grounded, more tightly confined worlds of Ted Chiang, Ann Leckie, and Cixin Liu, in which even the most futuristic civilizations struggle to shake off the quintessential banality of life in the twenty-first century. Visionary space operas, saturated with alien races and distant planets, are still being written, of course—Tom Toner’s recent Amaranthine Spectrum is the most ambitious series I’ve ever read—but they have a hard time landing on the bestseller lists, winning awards, or getting adapted to television. Not unlike the Apollo 11 command module currently gathering dust in the Smithsonian, this ambitious, highly fantastical sort of story has been relegated to a position of relative obscurity within the genre, sitting in the shadow of its more down-to-earth offspring.

The term “new space opera” was already around in the ‘80s. Like anything with the prefix “new,” its name precluded further taxonomies; but in this case the defining traits still seem to apply to the space opera of today. In a 2003 piece for Locus Magazine, the sci-fi writer Paul J. McAuley made the distinction:

while it may have been stuffed full of faux-exotic colour and bursting with contrived energy, most of the old school space opera was, let’s face it, as two-dimensional and about as realistic as a cartoon cel. New space opera—the good new space opera—cheerfully plunders the tropes and toys of the old school and secondary sources from Blish to Delany, refurbishes them with up-to-the-minute science, and deploys them in epic narratives where intimate, human-scale stories are at least as relevant as the widescreen baroque backgrounds on which they cast their shadows.

“Old school space opera” struggles in a radically changed zeitgeist. A growing preference for character-driven narratives has something to do with it, certainly, but “up-to-the-minute science” is something we can never go back on, and which itself only ever travels forwards. Different tastes make old school space opera undesirable; but greater scientific knowledge makes it implausible, and often impossible. Compare the much beloved Total Recall with its panned 2012 remake, for instance. The original’s Martian setting and some of the film’s more outlandish elements, including a cast of mutants who range from a sex worker with three breasts to a psychic homunculus who lives in his brother’s stomach, were scrapped in favor of a rehash of the same plot set entirely on Earth, and whose characters are nothing more or less than mere humans. It’s no coincidence that the film’s increase in plausibility (at least from a scientific perspective) correlates with a steep decline in narrative quality.

The original Total Recall was released in 1990, at the tail end of the Cold War and a fresh wave of similar, space-based stories across a range of media. Many of the sci-fi classics that came before it were even more imaginative, from flicks as visionary and philosophical as Solaris to the shameless absurdism of Barbarella. During the Cold War, our grasp of science may have been by today’s standards rudimentary. But the pace of development gave rise to a public mood of technological optimism despite the perennial shadow of the atom bomb. Space offered an escape, and sci-fi sketched—in gripping, atomic detail—the way out.

With China’s and America’s mounting investments in space exploration, we are now entering another space race, and perhaps another cold war. Against this backdrop, it would not be unreasonable to anticipate a renaissance in visionary space opera as a cog in the cultural logic of the early twenty-first century, just as recent advances in AI and virtual reality have been met by—and in some cases facilitated—major artistic investigation in film, literature, video games, and other media. The fact that this has not come to pass—and that few are treating Dune and Avatar as anything more profound or prophetic than candy shop fantasy—must stem from the fact that so much post-war sci-fi postulated that the early twenty-first century would see the moon colonized, Mars terraformed, and Earth adrift on artificial thrusters. Many of the huge astronautical advances that separate now from then have only gone to show just how empty space is, and brought us close enough to the ceiling of our technological potential that we can see the harrowing blandness behind the dazzling canopy of the stars. If any scientist’s postulation has aged well, it is that of Enrico Fermi, who in 1950 claimed that if aliens existed, they would surely have visited us by now. Over seventy years on, humanity is still waiting on that call.

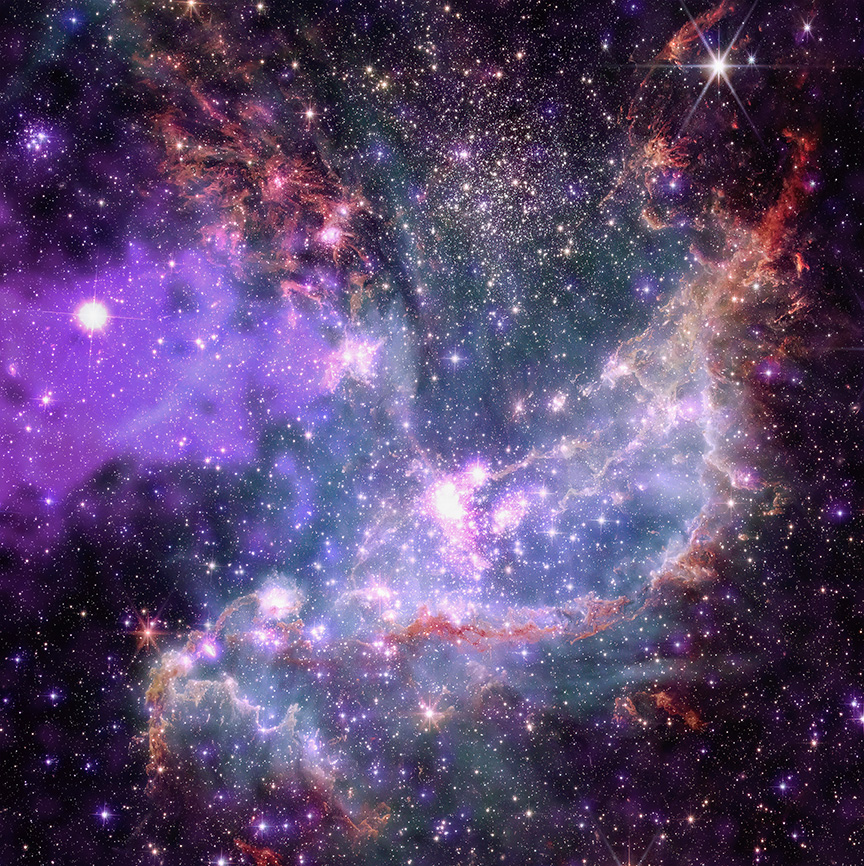

When it comes to the most expensive business in—and beyond—the world (space exploration, that is; not Hollywood), no one ever seems to ask the cheapest of questions: Is it worth it? Nonetheless, the answers are readily predictable. One can easily see how a complete shutdown of the space industry might save the taxpayer a few dollars in the long run. (The James Webb space telescope has so far cost an estimated $10 billion, as we have seen, while the Apollo space mission itself took up an exorbitant 5.5 percent of the federal budget). But giving up like that might just as easily be interpreted as a total waste of the close to a trillion dollars that NASA, the ESA, the CNSA, and every other scrabblerack has already slipped into the slot machine without yet winning the triple cherries of intergalactic travel, or the discovery of extraterrestrial life. And as NASA will tell you, there have been some winnings—that is, investments with practicable payoffs. The agency’s annual spinoff reports document the tens of thousands of lives saved through related technologies such as personal locator beacons (although one could counter-argue that these might have been made quicker if the funds had been allocated directly). Satellites have allowed us to see Earth in greater, more holistic detail, and led in part to the late James Lovelock’s influential Gaia theory, which posits the earth as a self-containing system. And then there are those sporadic discoveries, those bursts of brilliant mystery which almost make up for the crushing void around them: comets that slough alcohol; images of varicoloured constellations that glitter like the spilt contents of a jewelry box; the discovery of distant “megastructures” that continue to captivate scientists—but only because we don’t yet know what they are.

There is no disputing that space exploration has contributed to human progress in material, spiritual, and technological ways. Yet it’s also worth considering the disadvantages of space exploration—even those about which we can, at this time, only speculate. What if we continue to discover nothing of scientific value, merely shrinking the game board upon which we play out our dreams and fantasies in the process? The stakes of this question are rarely addressed, as we have seen, because they are so elusive, encased as they are within a future we have yet to tap into. But when we do, one thing we can know for sure is that the consequences will be enormous.

Though they usually lack a background in astronomy or quantum physics, storytellers continue to play an important role in the discourse and discovery of space. But for all the time they spend in fiction, those whose job it is to imagine are better acquainted than anyone with the disappointing reality of fulfilling one’s dreams. In a talk for the 2017 Academy of Achievement summit, the Irish novelist John Banville described how even non-readers, namely his mother, struggle to escape the monkey’s paw. “Like Irina in Chekhov’s Three Sisters . . . [she] longed to go to Moscow, Moscow for her being Dublin. And at the end of her life she moved to Moscow, and of course it wasn’t Moscow; it wasn’t even Dublin. It was a dream, and you should never move to your dream place.” In corroboration, he went on to tell an anecdote about an anonymous young man who rang up Rita Hayworth to tell her that he would love to meet her one day, since he believed her to be the most beautiful woman in the world. “I’m not now,” was her response; she was at the end of her career. “Keep the dream.”

Such anecdotes are a dime a dozen, and yet the lesson we ought to learn from them still hits with the force of a full-blown revelation. Is it that we forget? That we ignore the warnings? The most likely reason is that we receive and acknowledge the message, yet still believe that the experience of seeing our dreams in the flesh is necessarily superior to the fantasy by virtue of simply being real. But if the rational part of our minds knows anything, it is that the wisdom of Rita Hayworth will have a hard time trumping the persuasive power of wanderlust.

Space opera stories sell us a dream destination just as surely as the Moscow & Leningrad Blue Guide,or any other holiday brochure, only on a much larger scale. They allow us to account for the unknown in innumerable ways, to project and play out our thoughts and philosophies. For the politically minded, they can inform and incubate utopian ambitions or dystopian scenarios, charming us with visions of paradise while also allowing us to temper the white heat of a dangerous idea in the cathartic waters of fiction.

But this is nothing new. The practice of populating the blank areas of the map with our wildest fantasies has a long pedigree in literature. Leaving aside science fiction, the twentieth century was notable for the fantastical fictions of writers like Salman Rushdie, Angela Carter, and Gabriel Gárcia Máquez, which exploited the blindspots in empirical knowledge and teased out miracles from the matters of everyday life. But the oxymoronic tension at the heart of “magical realism” reminds us just how tightly the first half of that label is tethered to the second. If we want to find “true” magic, we have to go back further, to a time in which writers could still postulate about mythical creatures and countries unknown. If Márquez was able to write about old men with wings and women floating to heaven as a feature of the Colombian experience, then the fourteenth century travel writer John Mandeville could recount the dog-headed men and wool-bearing trees of foreign lands with even greater conviction. Even if the author did not quite believe in the fantasies of his apocryphal travelog, there was no reason the largely sedentary readers of medieval Europe shouldn’t.

As humans we have an insatiable urge to know, a manageable ambition so long as one’s purview remains confined to the purely foreseeable: the upcoming bend in the road, your next payday, the hills you can see from your bedroom window. But whenever a black spot appears on the horizon, a flick through the history books assures us that the inevitable human reaction is to stamp it out, to channel all the energies of the imagination into stoppering the leak, lest the flimsy sailboat of what we know should be swallowed in the vast ocean of what we don’t. This goes as much for writers and explorers of the twelfth century as it does for those of the twenty-first. In his Storia delle Terre e dei Luoghi Leggendari, the Italian novelist and semiotician Umberto Eco explains how the tendency in modern “fantascienza” to place “bug-eyed monsters” on other planets has a precedent in medieval explorers hypothesising the existence of mythological creatures in remote, hitherto unexplored lands. Eco’s book itself takes the form of a catalogue of such examples. Before Cook discovered Australia, for example, Eco excerpts European reports about the Antipodes, which spoke of giants with enormous ears, men who walked on their heads, and a mysterious, ambrosia-like substance known as “ambulon.” Thus, some stories enticed readers—or listeners, more likely—to set sail for the unknown, while others scared them away; but all instilled a sense of wonder and reverence for these far-away worlds.

The idea of a mysterious horizon goes beyond the merely spatial, and miles and meters will only get you so far when it comes to measuring what is, at bottom, a feeling, a shifting shape whose dimensions are cerebral. In fact, there is an argument to be made that even the earliest stories—the myths, which is simply the Greek synonym—were, if not science fiction, a kind of science by fiction. Scire is to know, fingere to make up, and even those ancients who did not speak Greek or Latin were prone to explaining the inexplicable with recourse to stories. Thus, for the Mesopotamians, rivers, seas, lakes, and oceans all obeyed the mysterious proclivities of different gods. For the Aztecs, the moon hied through the night in search of prey to eat. The aspect of sacredness was crucial to this transubstantiation, for it imposed a boundary that could not be crossed, or at least could not be disrespected by “scientific” inspection. Foreign lands might be colonized, the colonizers’ fantasies flattened into reality. But not the gods.

The rise of monotheism in Eurasia had a tangible dimension to it: the ascension of the old pantheon’s single surviving deity from Mount Olympus to the dizzying heights of heaven. With paganism pushed to the periphery, suddenly nothing on earth was out of bounds, and the curious-minded finally felt brave enough to examine nature a little more closely. Even so, the natural world was still dimly flavoured with the old holiness—they were still God’s, after all—so that medieval thinkers such as Thomas Aquinas or Al-Nuwayri could claim that earthquakes were weapons of God’s wrath, or that rain was the result of Allah milking the cow-like clouds. And that is to say nothing about the celestial realm, the Kingdom of Heaven itself.

What has any of this to do with space travel, with Martians and ring-worlds and the intergalactic civilisations of the putative future? Ostensibly nothing, but functionally everything, for sci-fi—as opposed to fantasy—operates by the same logic. All that separates the genre from these earlier myths is the target of its conjecture and the omission of religious influence. Like Manilius and Mandeville, the pioneers of sci-fi were merely glimpsing around the corner. The difference is that by the nineteenth century, the field of view—that blurry vision of the over yonder, the just ahead—had graduated from foreign lands to subterranean worlds and the known bodies of the Solar System. Few now can appreciate the sense of wonder which accompanied contemporary theories of Hyperborea, or Marshall Gardner’s “Hollow Earth” hypothesis—a wonder which, for all the naïve delightfulness of these theories, would not have sprouted were it not for the germ of plausibility rendered by the glaring gaps in Victorian science. If anything, the less serious propositions of fiction—Verne’s interior of the earth with its dinosaurs and giant mushrooms, H.G. Wells’s moonwith its insectoid Selenites, Edgar Rice Burroughs’s monster-filled Pellucidar—were even more wonderful, since they were stories, replete with awe and wonder and danger all rendered through the prism of human experience. Seen in this light, Verne is only a stone’s throw from Mandevillle, Wells a short spaceship ride from Manilius, and the only major generic difference is the removal of all surviving residues of divine inviolability, a process set in motion by the decline of polytheism. Far from deterring readers, science fiction, with its visions of technological utopia—then a more credible notion—provided the scientists and inventors of the time with a blueprint for transforming these mere fictions into fact. And even the stories whose authors opted for a more dystopian setting invariably display a range of inspiring high-tech inventions with which their protagonists navigate—and ultimately triumph over—the hellscapes and wastelands in which they find themselves.

The reciprocal feedback loop between science fiction and technology was not always obvious. In the West, writers such as Neil Gaiman and Kazuo Ishiguro have only recently made the point, but the evidence is now so compelling that Chinese society has recently flipped from (broadly) viewing sci-fi as a “spiritual pollutant” to a convenient vehicle for projecting itself into the geo- and spatio-politics of the future, as the injection of funding into the country’s space agency and the success of films such as The Wandering Earth in Chinese cinemas has shown. You could say there is a democratization at work. Even as the exotic allure of space wanes, shifting social attitudes are gnawing away at the twin deterrents of impossibility (the sheer difficulty of getting into space) and unpopularity (space’s erstwhile status as the exclusive domain of gods and geeks).

For some leading scientists, space exploration is not an exercise in optimism so much as a survival mechanism. The likes of Carl Sagan and Michio Kaku have expressed the need to migrate away from an irredeemable earth threatened with catastrophe, as though it were a faulty battery, rather than prioritize fixing the planet and providing foundations for a sustainable future. The solution is myopic at best, and at worse seems an excuse to forge ourselves a licence to continue destroying the environment, so long as we can hop onto other ones in the vain hope of outpacing destiny.

Again, human imagination will be the first victim of this unsustainability cycle; it already is. In spurring readers on to invent new gadgets and uncover distant worlds, the early gospels of sci-fi were complicit, albeit indirectly, in their own fate. New discoveries and inventions replaced those that came before them, only to be replaced in their turn in a seemingly endless cycle of obsolescence and innovation.

Nor is it much wonder that as early as 1967 Isaac Asimov, that giant of science fiction, took note of this same process playing out in the cultural domain, remarking that

because today’s real life so resembles day-before-yesterday’s fantasy, the old-time fans are restless. Deep within, whether they admit it or not, is a feeling of disappointment and even outrage that the outer world has invaded their private domain. They feel the loss of a ‘sense of wonder’ because what was once truly confined to ‘wonder’ has now become prosaic and mundane.

If it were not for their reputations as founding fathers of the genre, the stories of Wells and Verne and even Asimov would likely be considered just as “prosaic and mundane”—and therefore neglected—today as the stories of Enrique Gaspar, inventor of the time machine (or at least the idea of it).

A story putting its own inspirations to shame might be the literary equivalent of kicking one’s parents out of the house. But when those inspirations become logically impossible under the light of a new scientific or technical discovery, insult is added to the injury, and the kids ought to bear at least some of the responsibility for egging on those pesky scientists. In Farewell Fantastic Venus, a 1968 anthology of short stories by leading science fiction writers about Earth’s eponymous “Sister Planet,” editors Brian Aldiss and Harry Harrison were probably the first to address this phenomenon specifically in relation to space travel: “We have landed what is now a load of metallic junk on [Venus]! Should we celebrate this success or mourn the death of the legends?” The legends they refer to are the Hebrew and Mesopotamian legends, in which the planet Venus was just as much a goddess as in their Roman spin-offs, but this notion of recurring obsolescence undergirds the anthology. Early “Cytherean” stories, as Aldiss and Harrison call them, such as Achille Eyraud’s Voyage to Venus and John Munro’s A Trip to Venus, had the habit of rendering Venus a faultless utopia, whose terrain tended to resemble a silver-misted landscape or at worst a benevolent swamp. But in July 1962, the Mariner II rocket determined that the surface of Venus is, below the clouded atmosphere, an 800-degree °F hellscape. Tough material to work with, but writers such as V.A. Firstoff and Poul Anderson made do, only for their own stories to be rendered obsolete by subsequent missions which discovered that the planet suffers constant, vicious dust storms, that the surface is even hotter than Mariner II postulated, and that where the building blocks of life may have lain, there was nothing but rock.

All this begs the question: If and when we properly map, say, the Canopus star system, what will happen to Dune? Unless Frank Herbert was gifted with godlike foresight, his magnum opus will suddenly find itself homeless, and none of the remaining tenants of terra incognita can be expected to violate canon by accommodating it. Dune will be exposed, done for, and will share the same fate as Journey to the Centre of the Earth, The First Men in the Moon, The Martian Chronicles and all those other novels with such exciting titles. To be sure, we can compensate for the end of Dune by appointing a successor even farther off—and so on and so on. But there may come a point where we will have mapped the universe, past and present, or enough of it to extrapolate conclusions, and—going by our current record—discovered nothing as vivid or diverse or liveable as Earth, erasing the immense potential which obtains in every square inch of unexplored space. The quest for knowledge is often dressed up as a quest for survival, but it can just as easily be the death knell for the kind of storytelling that sustains us and gives meaning to our existence. Just as a story about a historical figure would be utterly impossible if we knew every atom of her being, every action she undertook, every moment of her life, a totally known universe would leave little space for authors to sneak in and do their magic. We will no longer tell these stories not because, in this technological telos, we will no longer have need of them—but because we will no longer be able to.

Of course, this is an extreme example; humanity will be extinct long before the contours of the universe are ever mapped out, not to say contained—for they are, scientists assure us, always expanding. Still, this is the horizon to which we find ourselves hurtling today. Although only a few decades old, Total Recall would be unthinkable now. The same goes for the science fiction of Edgar Rice Burroughs, H.G. Wells, and nearly all their contemporaries. Comparatively anodyne, well-researched stories such as John Scalzi’s Old Man’s War are safe for now, but only until significant flaws in their spatial or structural logic are uncovered by the latest advances in engineering and physics. Perhaps it is better, somehow, to maintain the illusion indefinitely—to keep the dream, rather than exchange it for disappointment.

Josh Allan is a writer based in London. He graduated from the University of Manchester with a BA in English Literature with Creative Writing, and from the University of Oxford with an MSt in World Literature. His work has appeared in The Oxford Review of Books, World Literature Today, 3:Am, Quillette and other publications, and he is currently working on a post-apocalyptic science fiction novel.

This post may contain affiliate links.