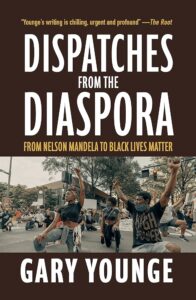

[OR Books; 2022]

Early in my foray into Gary Younge’s Dispatches from the Diaspora, exhaustion started to set in. I felt it in my back, as if someone had injected lead in my veins. This was a familiar tiredness, the same kind I felt as a college activist following a parade of Black deaths at the hands of the police, and later as a journalist watching long-awaited “reform” die on Capitol Hill: Again?

Or, better yet: Still?

Dispatches from the Diaspora: From Nelson Mandela to Black Lives Matter is a journalistic anthology spanning Younge’s twenty-eight-year career, much of it at The Guardian, where he writes to this day. And the skill he’s accrued over these years is clear: Dispatches is deftly reported, soberly narrated, and surgical in its appraisals of racial politics around the world.

In the introduction, Younge admits that he had to square his identity with his career aspirations. Generations of Black writers—including myself—have come across this path as they venture deeper into the profession. And for all of us, there’s a split in the road: One sends the journeyman deeper into their Blackness, the other points them towards the opposite direction. Thankfully, Younge chose the former. “Like all journalists, I came into the profession with something—my identity,” he writes. “But unlike some, I am happy to own it and share it.”

Arguments about whether or not to be a “Black writer” are well-worn at this point. By placing his Blackness at the center of his project as a journalist, Younge has been able to make clear-eyed examinations of racial politics around the globe: from Nelson Mandela’s first presidential campaign in South Africa to the Notting Hill Carnival in south London to victory parties in Chicago’s South Side during Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential election. Younge has also exposed the sweeping, omnipotent presence of anti-Blackness with frightening clarity.

One of the book’s recurrent locations is South Africa, mostly because Younge’s first major journalistic milestone was his coverage of Nelson Mandela’s 1994 presidential campaign. Younge opens Dispatches with his impression of a Johannesburg township the morning of the election, as townies headed to the polls through a miasma of collective anticipation: “Dressed in Sunday best, nobody was talking,” he writes. “Nelson Mandela had described his political journey as ‘the long walk to freedom.’ This was the final march.”

Did Mandela’s election mark the end of this long march to freedom? Not really, no. In a 2001 dispatch titled “Life after Mandela,” Younge captures the political reality that so often follows such collective dreams: “At times here it feels as though everything and nothing has changed.” Apartheid has ended, replaced with democracy. But those of us living in failing political experiments have become all too aware of how democracy doesn’t necessarily mean freedom. What followed Mandela, instead, was the factioning off of the Black population between the working class and the elites. Former rebels have joined the establishment; the quest for liberation for all becomes a moment of opportunity for some. At one point, Younge notes that activist-turned-businessman Sakumzi Macozoma described South Africa’s new era in a tone reminiscent of “a dot com millionaire before the bust.”

Redirecting a people after moments of great societal upheaval challenges even the most politically upright, and there remains limitless potential for what Black political operatives should have done post-apartheid. Younge resists this impulse, choosing instead that elusive moment when a political movement officially becomes co-opted. “The pace of change is such that individuals cease to live in real time. Human journeys that under normal circumstances take decades, if not generations, are completed in a few years, if not months,” he writes. “So the prisoner becomes president; law breakers become law makers; armed guerrillas become arms dealers.”

Later on, Younge shifts his focus towards Alexandra, a township in Johannesburg. While talking to locals, he discovers an old rift remains unclosed. In 1994, he noticed that white liberals were preoccupied with symbolic issues surrounding figureheads, while the rest of the population worried about “poverty or disease or apartheid soldiers.” By 2001, that disconnect hadn’t been rectified. “When a provincial committee banned Shakespeare, because his work was ‘too gloomy’, and Nadine Gordimer, on the grounds of racism—their decision was reversed and immediately condemned by the African National Congress nationally—the news went all around the world,” Younge writes. “But it never made it to Alexandra, where those I spoke to neither knew nor cared.”

Does any of this sound familiar? Aside from being an accessible introduction to the global Black diaspora, Dispatches reinforces the old adage: “The more things change, the more things stay the same.” The forebears of today’s culture wars extend to Britain as well, as shown in Younge’s writing on The Macpherson Report.

On April 22, 1993, eighteen-year-old Stephen Lawrence, a Black Briton, was murdered in a racist knife attack while waiting for a bus in southeast London. Four years after an initial investigation failed to net any prosecutions, a high court judge named Sir William Macpherson mounted an inquiry into where the police failed. By February 1999, he’d generated a 389-page report that went on to transform policing in the UK. “This was our Rodney King,” Younge writes in his February 2000 report for The Guardian. “At last, here was proof of what Black people have been saying for years—that they have been falling foul not just of the law of the land but of the law of probabilities; evidence that there is a persistent and consistent propensity to shove ethnic minorities to the bottom of every available pile and not only leave them there but also blame them for being there.”

Sadly, this same passage could be applied, with nearly no changes at all, to the United States’ reaction following the infamous 2014 murder of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. But Younge’s observation of white Britons’ reactions to Macpherson Report managed to have even more staying power:

Among some, it triggered a process of introspection: white people suddenly realised they were white in a way that they had not considered before. And they were confronted with the fact that this whiteness conferred power, privilege and responsibility. Others reacted aggressively, annoyed at the assumption (which only they made) that they were condemned by virtue of their whiteness. Either way, white people were forced into an acute awareness of a matter that had fluttered only on the periphery of their consciousness.

Reading Dispatches was, more than anything, affirming in the worst sense, like venturing further and further into the cosmos seeking new life, just to find that we were alone all along. The book illustrates how anti-Blackness adapts to whatever environment it’s placed in like a creature hellbent on survival. Younge himself notes in the introduction how the coronavirus pandemic revealed this state of affairs even more clearly: “The disproportionate number of Black deaths across the globe during the Covid-19 pandemic exposed the degree to which racism itself remains a hardy virus that adapts to the body politic in which it finds a home, developing new and ever more potent strains.”

This isn’t to say that Younge’s book is pessimistic by design. There are hopeful strains throughout, particularly in his coverage of the Notting Hill festival, a paean of Afro-Caribbean expression. But racism isn’t designed to be hopeful, which is why resistance remains a crucial aspect to Black living. “Imagine a world in which you might thrive, for which there is no evidence,” Younge writes. “And then fight for it.”

Kaila Philo is a journalist and researcher based in Washington, D.C. Her work has been featured in The Atlantic, The Baffler, Jewish Currents, and more.

This post may contain affiliate links.