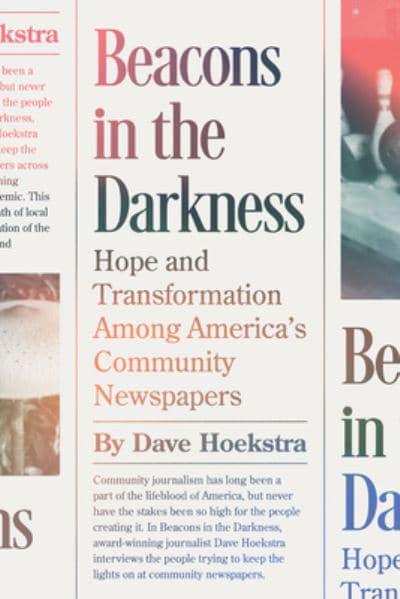

[Agate Publishing; 2022]

Dave Hoekstra, winner of the Studs Terkel Community Media Award (2013), is a career journalist devoted to the work of community betterment through community newspapers. He was a critic and columnist with the Chicago Sun Times for nearly four decades, co-produced an Emmy-nominated PBS special on the Staple Singers and their contribution to the Civil Rights movement, and has three previous books published by Chicago Review Press.

Beacons in the Darkness: Hope and Transformation Among America’s Community Newspapers is his newest work, out in 2022 from Agate Publishing. Begun in 2019 and finished in 2022, it chronicles the tumultuous shifts in and demise of a robust community newspaper culture responsible for providing a substantive sense of place and connection for people across the United States.

Hoekstra’s new book seeks out places where local news survives and illuminates some of the uncanny practices allowing independent newspapers to thrive in pockets across the country. He investigates how some newspapers are integrating the latest technologies to evolve with subscribers and touches on how the Black Newspaper changed and continues to change America. He traces migratory paths of journalism and looks at how family newspapers are the antidote to Big Media’s fake news machine.

It is undeniable that community journalism and the free press facilitate equity. Newspapers help people cultivate a sense of place, and to understand what that means. Independent journalism is as essential as the public utilities that many of us take for granted. Local news is the first draft of a people’s history. It’s how we hold public officials and corporate entities accountable, connect with city government, exchange crucial information such as who’s getting married, who died, and how. As the local news-gathering process continues to break down, the first draft of our collective history is actively disappearing. In a world devoid of local newspapers or orators, we’re at the mercy of Big Data to know our neighbors. Consequently, we suffer the demise of entertaining at home, block parties, and lose the art of visiting.

Hoekstra’s interviews and case studies prove this fact beyond a shadow of doubt and illuminate tragic consequences of their absence over the course of fourteen chapters. Chapter titles include, “Seeds of Change,” “Stop the Presses! Technology Has Come to Town,” “Migratory Paths and Connections,” “The Truth About Fake News,” and “The Virus Crisis of 2020.” Beacons in the Darkness is a timely book that chronicles a turning point for community newspapers.

Hoekstra found his North Star for this book in the small southern town of Hillsborough, Illinois, home of the Journal-News and its fifth-generation owner/publisher, John Galer. Hoekstra frequently circles back to Hillsborough throughout the book. The book’s heartbeat, for me, is Chicago. I’d read an entire book based on this coverage of the Chicago Reader.

One of most transformative and hopeful elements of the book is Hoekstra’s profile of a married millennial couple who moved from NYC to Marfa, TX, and bought the Big Bend Sentential in 2019 from an elder married couple who’d been running the local paper for over twenty years. They are nourishing a local ecosystem around the paper, beginning with community gathering space—a place to exchange and discuss the news of the day. Their newspaper headquarters also serves as “a place to get coffee or a bite to eat, exchange information, and support thriving local independent journalism.” Kabat and Crow’s focus is supporting journalism through diverse revenue streams that also bolster the sense of place and community fostered by a local paper. It’s an approach that reads as both enjoyable and economically sustainable.

In Arkansas, Editor and Publisher Magazine’s 2008 publisher of the year Walter Hussman, who runs the Democrat-Gazette, leaned into technology to cut costs. He invested in more than eighteen thousand “newspaper iPads” for their entire community of subscribers. His small team then spent months traveling to over twenty-five rotary clubs across the state endeavoring to teach every subscriber how to use and benefit from their new iPad. This approach, of lavishing consumers with customer service like they had never seen before, paid off by retaining a sustainable invested subscription base while significantly cutting long-term print and distribution costs.

It all comes down to place, and sometimes (perhaps more often than we’d like to admit) generational wealth. The value of community is impossible to measure against capitalist economic realities. This is always at odds with the bottom line, which seems to be that independent community newspapers aren’t economically sustainable. In most of these stories, they continue to thrive only with the support of diversified revenue streams. And an abundance of free labor.

If a spirited newsroom leads to a vital future, then what is the frail state of local news across the country leading to? If community newspapers are akin to public utility, what is lost when local papers are absorbed by nonlocal corporations or disappear altogether? This book meditates on such questions, unpacking connections and digressions between place, identity, and technology.

Hoekstra notes that a free press is not free. He cites journalism as being shaped by the “American work ethic of character and persistence.” It is equally shaped by harsh economic realities driving the decisions of even the most dedicated publishers and distributors of local news.

Our cultural obsession with an “American work ethic” perpetuates the puritanical pyramid scheme of relentless work leading to morality and success. In reality, it’s a recipe for burnout and poor health. As I read interviews chronicling one newspaper owner’s recent suicidal thoughts, and another’s discussion of sacrificing opportunities at marriage and family for a life devoted to newspaper work, I wondered if that same ethic is a simple disguise for the pervasive and devastating capitalist ideal of hard work above all else. And if it is actually another driving force behind the demise of community newspapers.

According to Hoekstra’s case studies, in order to truly carry on the public service legacy of a community newspaper, creativity, skill, and commitment aren’t enough. One must be ready and willing to work more than fifty hours a week consistently and tirelessly, for years, with no time off, for very little pay.

Is there a world in which the commitments to rest as resistance and sustaining local journalism can exist harmoniously?

Place is essential to our individual and collective sense of identity. Locally owned newspapers exist in the nexus of place, identity, technology, and economics. With the demise of democracy accelerated by a vacuum of local voices across the country, what’s next for us? How can we revive these essential venues for recording and circulating the people’s history? And how can we infuse our communities with the spirit of experimental thinking as they pixelate into the metaverse before our very eyes?

Beacons in the Darkness surfaces these questions, and illuminates some possibilities and problems without providing conclusive answers. I want to love this book. And yet, despite some inspiring moments, I found it frustrating, perhaps because it lacks the reassurance I desire. The hope and transformation mentioned in the title are often hard to locate despite Hoekstra’s insistence that it’s a book about the “vanishing terrain of community ties and dedication to the common good, a celebration of the potential of the newspaper model,” and not an elegy.

Hoekstra conducted over fifty interviews with sources covering ten states and seventeen papers, with seven located in Illinois. I think of the Climax Crescent, one of the only local papers remaining in proximity to my folks’ rural Michigan home. He doesn’t mention the Climax Crescent, nor does he cover the Arizona Informant, a weekly paper I subscribe to that is headquartered here in Phoenix, AZ, reaches over 100,000 readers, and remains dedicated to recording Black History.

I wonder how many other local papers are still in business, and long for a more extended and inclusive list, or even an appendix of locally owned and operated papers.

Beacons in the Darkness is a bit dry in places and occasionally reads like a convoluted family tree of several local newspapers throughout the US. I want more synthesis. Some of the narratives such as that of Galer’s Journal-News in Hillsborough, grow repetitive as they’re parsed across several chapters and dissected for fresh angles. At one point, Galer calls himself a dinosaur who doesn’t live in the real (money-driven) world. And, by all accounts in this book, he’s right. While the historical treatments and family trees provide essential and substantial context for the state of independent journalism today, they don’t always serve to further hope and transformation. I wonder what a sequel might do towards furthering those qualities.

Anyone looking to be convinced of the value of the free press, look no further. Beacons in the Darkness: Hope and Transformation Among America’s Community Newspapers will find its ideal audience in rural America with the old heads who already love community newspapers and independent journalism in addition to anyone wanting a survey of local newspapers in this country, today.

Ada McCartney writes from Arizona and elsewhere. She holds an MFA from the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at Naropa University and a BA from Kalamazoo College. McCartney is a poet and teaching artist. She is author of cunt(In Process, 2021) and an editor of the anthology More Revolutionary Letters: A Diane di Prima Tribute (Wisdom Body Collective, 2021). McCartney collaborates with the FEMME ON and Wisdom Body collectives. Her writing is featured in Corporeal, en*gendered, Plants and Poetry Journal, The Bombay Gin, Phoenix Dance Observer, and elsewhere. Connect with her at www.aamccartney.com.

This post may contain affiliate links.