This essay was originally published in the Full Stop Quarterly “Cultural Politics of Land” issue (Fall 2023). Subscribe at our Patreon page to get access to this and future issues, also available for purchase here.

In 1532, Francisco Pizarro set foot on the coast of Northern Peru and established one of the oldest colonial cities in South America. Taking from the Indigenous language of the very people they set out to conquer, the Spanish named the city Piura, from the Quechuan word pirhua, meaning abundance. The Quechuan word honored the land’s biodiversity and importance as a water source, while the Spanish seizure, both literal and linguistic, transformed the meaning and landscape of Piura into sites of extraction.

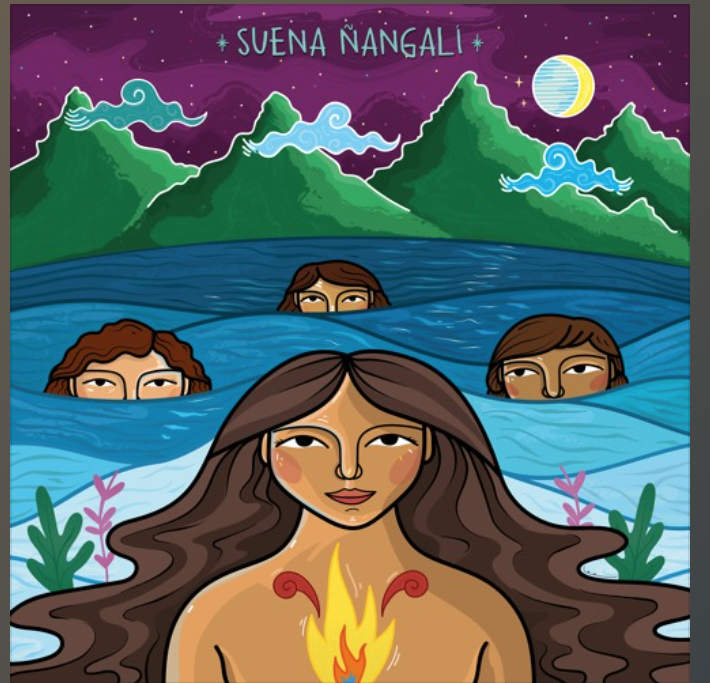

However, in the centuries since this portentous naming, meaning and landscape have not remained uncontested in the Peruvian Andes. Movements for territory defense have proliferated, struggled, and won victories, despite facing off against massive mining projects supported by state police. Furthermore, radio, social media, and popular art have been crucial as avenues for disseminating information, fomenting solidarity, and making meaning of anti-extractivist struggle in the face of pro-mining propaganda. It is on this cultural front that the audiovisual Latin American collective Maizal worked in Piura for their stunning experimental sound project, Suena Nangali (Nangali Sounds). Over the course of a year, Maizal collected sound recordings of the wildlife and waterflow of the Andean moorlands under threat from mining, as well as interviews with veterans of anti-mining activism from the pueblo Nangali. The result is an imaginative archive and ambitious cartographic experiment that details (but cannot capture) the life-affirming relationship to land that is at stake for communities struggling in anti-extractivist territory defense.

*

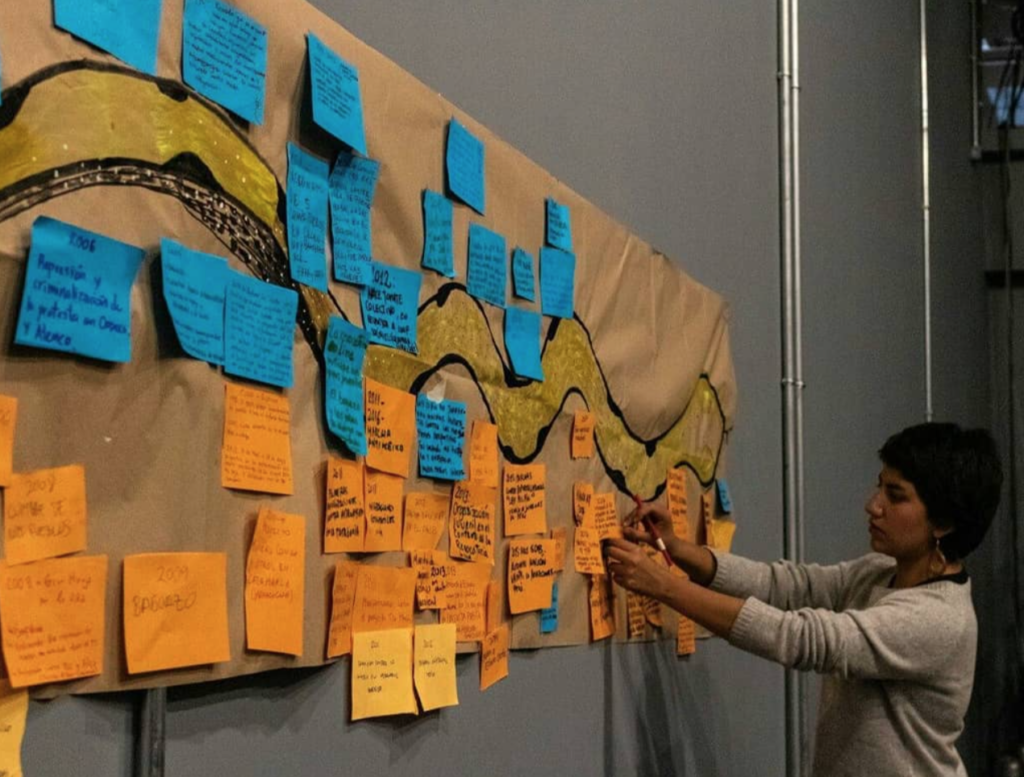

Maizal began around seven years ago as the Youtube channel and passion project of Julio Gonzalez and Luz Estrello. The two met in their masters program for visual anthropology in Ecuador during a heightened period of street protests against the expanded extraction of petroleum in the Amazon rainforest. They began documenting the 2013 protests, inspired by the movement for free media. In an interview I conducted with Luz last year, she clarified, “We didn’t study film, we studied autodidactic photography informally in workshops many years ago, but we went along learning collectively. What Julio learned, he taught me, what I learned, I taught him, and the same thing with other people who started joining Maizal.” Pedagogically, Maizal’s approach to creative training resonates with the influential teachings of educator Paulo Freire, who championed dialogical methods for being “the essence of education as the practice of freedom.” This collaborative pedagogical ethic became a central pillar of Maizal’s project as they began hosting workshops on audiovisual production and collective mapping for campesinos and territory defenders. In this way, the collective extends their knowledge to people mostly removed from the gallery circuits of the art world and the formalized training of the academy. One of Maizal’s first projects as an art collective was to host workshops with the children of a community in Junin, Ecuador whose land was being targeted by a mining encampment. Police had occupied the town and employed intimidation tactics by imprisoning movement leaders and surveilling the community for months. In this violent context, Luz and Julio hosted workshops for children that combined techniques of filmmaking with methodologies of collective mapping for the group to reflect over their territory, their lives, and what places were most meaningful to them. Luz described to me the intentions of the exercise, which were not solely comfort or entertainment but also clarity and reflection: “Through a simple drawing exercise of drawing the map of your pueblo and community, many things appear—characters, memories, relationships of power, the theme of the mining companies, the anti-mining activists, and how the children were processing it.”

In Manual of Collective Mapping: Critical Cartographic Resources for Territorial Processes of Collaborative Creation, Pablo Ares and Julia Risler write:

Mapping should be part of a wider process, “another strategy,” a “means for” thoughts, the socialization of knowledge and practices, a boost for collective participation, a challenge to hegemonic areas, the driving force for creation and imagination, a deep analysis of key issues, the visualization of resistances, the mark highlighting power relations, among many other aspects.

Indeed, Ares and Risler’s lengthy definition leaves one wondering if mapping can truly accomplish all they set out for it to accomplish. Yet Maizal’s work serves as proof that mapping can do all this and more.

The workshops not only democratize the means of cultural production but also catalyze lasting relationships among non-professional artists and organizers with a shared anti-extractivist politics and investment in collective artmaking. Luz and Julio worked with the community in Junin for years and remain close with them. When I asked Luz how Maizal had affected or changed her life personally, she laughed joyfully and responded, “For me Maizal is proof that even as time goes on, when networks are sincere, when they’re loving, when they’re profoundly sincere with what we want to do communally, those relationships will persist. That to me has been very important because it also implies the confirmation that solidarity, cooperation, and communal life is the life we want to live.”

Luz thus envisions the constitution of the collective as a praxis of communalism in the present that aspires toward a horizon where practices of care, reciprocity, and mutual aid can be freely cultivated. Maizal’s praxis of communalism also rejects the individualism and artist-as-singular genius concepts that have been integral to Enlightenment theories of aesthetics and to the art market branding of individual artists. Scholar Arne de Boever argues that these theories are premised on an “aesthetic exceptionalism” whereby artists and “capital A art” are exceptionally capable of producing compelling work as compared to “normal” people and pop culture. Immanuel Kant’s Enlightenment notions of genius and the sublimity of aesthetic beauty have been rigorously challenged (by de Boever himself), yet as de Boever argues in Aesthetic Exceptionalism, “exceptionalism is widespread in the art world, and is implicated in the art world’s economic and political order. Indeed, it is profoundly rooted in Western thought.” Cultural production, of course, is always a form of work, even as certain artists and theorists of art might speak of inspiration and spontaneous genius. The skilled/unskilled laborer divide that rationalizes the extraction of profit from underpaid workers also applies to an extent in the art world, insofar as the value of the creative product is linked to the producer’s institutional affiliation, training, and years spent in the market.

Not every art collective takes a stand against aesthetic exceptionalism and individualism by virtue of being a collective. However, Maizal’s methods of popular artmaking, workshop-style production, and horizontal training is material anti-individualism in practice. Luz told me that her experience with Maizal made her conceive of work in a different way. She was thankful for how “these networks have allowed us to create and manage other things, so we’ve been able to work and live in our jobs as researchers and communicators, thanks to communal work.” In this sense, Maizal’s communalism is not only an egalitarian rejection of the artist-as-singular-genius, but also a generative division of labor allowing people with jobs and obligations to pursue artistic projects outside of the totalizing identity of “artist.” Under capitalist violence and resource accumulation justified by logics of profitability and scarcity, the “life we want to live” is not only repressed but rendered unimaginable. The question of how we imagine another way of living is an ideological, pedagogical, and aesthetic question; no one of these terms can truly be isolated from the others. Consequently, regarding the question of producing alternative imaginaries, anti-hegemonic cultural production is uniquely positioned to respond to the challenge of retaining this link between the sensorial and the ideological.

*

Suena Nangali intervenes at this juncture between the sensorial and ideological. The website that hosts the project describes it as “a research and collective creation project that explores the relationship between nature, territory and community through audiovisual language, especially interested in sound as sensation, and also as a carrier of social meanings.” Although Maizal is credited as executive producer and central coordinator of the project, it would not be entirely accurate to say Suena Nangali is Maizal’s. The project brings together artists from Bolivia, Ecuador, Peru, and Mexico in collaboration with organizers from the Asociación de Mujeres Protectoras de los Páramos, or AMUPPA, a group of women based in Piura who work on ecological conservation and territory defense. Splicing together distorted soundbites of field recordings with direct quotes from community members of Nangali, Suena Nangali dislocates the listener from a straightforward contemplation of the sounds of nature. In other words, Suena Nangali forgoes the nostalgic sentimentalism of a defeatist, static archive, whereby the field recordings preserve a beautiful purity soon to be bygone in the age of mining. Luz made sure to clarify as much when I asked her to reflect on Suena Nangali’s archival politics. She responded that the intention was that the archive “be alive, not just be there safeguarded, or follow the logic of an anthropological rescue. ‘Oh, the paramos [Andean moorlands] are disappearing, and we have to rescue the sound!’ No, we don’t want the paramos to disappear in the first place! We want to register the sounds so more people can listen and know them, not to rescue them from imminent destruction. Destruction is precisely what we are trying to avoid.” This ethos keeps the hope and power of organizing territory defense alive in the work even as the reality of environmental catastrophe must be registered and mourned.

Furthermore, the foregrounding of human voices, sometimes longing, sometimes polemical, circumvents the romanticism of the “untouched landscape” that has informed racist nature conservation. The early conservation movement in the United States, most famously exemplified in the creation of Yosemite National Park, preserved “untouched landscapes” through the expulsion of Indigenous communities in a practice that has been called “fortress conservation” by contemporary critics. Prakash Kashwan, a scholar on conservation policy in India, Mexico, and Tanzania writes that “American environmentalism’s racist roots have influenced global conservation. Most notably, they are embedded in longstanding prejudices against local communities and a focus on protecting pristine wildernesses. This dominant narrative pays little thought to Indigenous and other poor people who rely on these lands—even when they are its most effective stewards.” By centering Indigenous territory defenders in its cartography of the landscape, Suena Nangali challenges the cleaving between humans and their territories that informs overly simplistic notions of landscape and erases the importance of Indigenous sovereignty in the land politics around conservation. It is the relationship between the pueblo of Nangali and the moorlands of Piura that is the focus of Suena Nangali, rather than just the figure of the sanctuary sans humans.

In the track “Farmacia,” this relationship is framed as a reciprocal and necessary form of care. The title immediately indicates the significance of the anti-mining struggle for the preservation of Indigenous practices and Indigenous life itself: The pharmacy of the community is at stake. The track begins with bird sounds that blend into the voice of a woman detailing the benefits of various plants of the moorlands. “San Pedro will help you get rid of a cold,” she says over the chorus of birds. (San Pedro is a cactus that has long been used in Andean traditional medicine and divination.) A baby, presumably her baby, gurgles as she continues to talk about the importance of the plants for taking care of her children. More children laugh. The scene is peaceful, warm, and would be idyllic were the listener not cognizant of the political situation framing the interview. Then the sounds of birds, mother, and children fade out and are replaced by industrial sounds that morph into a staticky and somewhat off tempo beat.

“Farmacia,” like most of the tracks on Suena Nangali, is an exercise in active listening that is not always pleasant yet whose very abrasiveness is true to the tensions in the struggle for land. The reality of Nangali is that it is not all healing. Suena Nangali is a sonic cartography of a community and territory under threat, and that threat sonically interrupts the human voices and the field recordings in the mapping of the space. Is the loud mechanical beat in “Farmacia” overtaking the speaker and the animal sounds the sound of mining machinery and rocks tumbling? Is it a song or message lost in interference and static? Is it the marching rhythm of someone or something invading the paramos? The beat has slight resonances with the rhythm of a goose-step march, the classic military march step for parades. However ambiguous, the harsh interruption makes clear that what it interrupts is vulnerable, can be overpowered, and must be defended. The necessity of defense informs the reciprocity of the relationship between pharmacy and community, each dependent on the other. As the strange beat fades out, the voice of the woman returns and says, “We have to protect what God gave us. That’s what we have to struggle for: for our plants to survive. We have to appreciate them as though they were our own life, because they give us life.” The woman in the song praises the exceptional benefits of traditional medicine, but also contextualizes it as a lifeline in the survival of a community facing precarity and economic instability. She adds, “when you don’t have money, what are you going to do? What are you going to do without natural medicine, if you want to live at least a moment longer?” Her wording, “a moment longer,” reflects the moment-by-moment life and death conditions in Nangali, not only from the mining company targeting Piura but from the structural violence of poverty that makes the farmacia ever more important.

The role of care in maintaining struggle cannot be understated. Head of the FBI J. Edgar Hoover called the Black Panther’s Free Breakfast Program “potentially the greatest threat to efforts by authorities to neutralize the BPP and destroy what it stands for.” When communities marked for death by the state take care of themselves, they disrupt the state’s monopoly on ensuring social reproduction and sabotage its control over life and death. “Farmacia” reminds the listener that care practices are not just gifts of love or a form of symbolic resistance, but a material necessity to confront the threat of death. In the colonial period of Latin America, the use of Indigenous traditional medicine was outlawed not only because it undermined Catholic hegemony, but because its role in autonomous social reproduction and intracommunity care challenged total colonial domination.

The autonomy of care is crucial in struggles for Indigenous sovereignty as mines have pivoted towards philanthropic pursuits through the adoption of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). In masterful PR moves designed to assuage critics, mines in Peru have been investing in reforestation and education initiatives for rural communities. By funding infrastructure and agriculture, the companies coerce vulnerable populations into positions of dependency that strategically benefit mining interests. In his research on CSR policies in the Peruvian province of Santa Cruz de Succhabamba, Michael Wilson Becerril writes that “these tactics help explain the opposition’s slow demobilization and the company’s successful installation into the community by 2008. In a province where over 60% of the population was classified as impoverished in 2007, the company presented powerful incentives.” The situation mirrors the words of the speaker in “Farmacia”: “When you don’t have money, what are you going to do?”

Yet, “Farmacia” does not leave this question open for the mines to answer; the speaker answers her own rhetorical question by insisting on the importance of the land’s flora and its medicinal properties. She tells the story of her own grandmother being a skilled curandera (medicine woman) who trained herself to forage because her community did not have water access to cultivate medicinal plants. The story of skill arising from necessity echoes the speaker’s own point on how poverty and lack of medical resources sharpens the importance of community based traditional medicine. This is especially so when mines are offering limited amounts of support to the local community in return for the right to extract resources from the land.

However, the horizon of “Farmacia” cannot be limited to a utilitarian valorization of the effectiveness of traditional medicine. The speaker is not arguing that medicinal plants alone materially counteract the deep effects of poverty, but that they play a role in enabling autonomous forms of care for Indigenous people. One reason I align traditional medicine with care practices in resistance is because care does not just mean sustaining the physical body, but also transmitting intergenerational knowledge, valuing the dignity of people and their autonomy from mines, and honoring ancestral practices. Struggling for the plants means struggling for the right to Indigenous epistemologies in addition to the right to territory. Scholar Boaventura de Sousa Santos has called the colonial and neocolonial suppression of Indigenous epistemologies a form of “epistemicide,” whereby knowledge systems are silenced, devalued, or annihilated. The speaker in “Farmacia” mournfully notes that “medicinal plants are very curative, but we don’t know how to cultivate them, how to seed them in our gardens. Sometimes out of ignorance we don’t know how . . .” The “we” in her phrasings appear to be a communal “we” of Nangali, or possibly “we” of the younger generations. It is clear from earlier in “Farmacia” that she, as an individual, is knowledgeable about plants and has used them. The invocation of the communal gestures towards one of the most meaningful effects of learning and defending traditional medicine: mutuality and horizontal healthcare. The life at stake in care practices need not be simply the fact of organic matter surviving, but also the hope that communities be free to practice, preserve, and honor what and whom they choose, which includes honoring autonomy and each other. The aspirational element in Suena Nangali foregrounds what Luz mentioned in our conversation: the possibility of imagining and living life as one chooses.

Even as the mines’ injection of capital into rural infrastructure grants them power over communities, it does not ensure community acquiescence. Nangali has been resisting the Rio Blanco Copper Mine for twenty years, according to Luz. She told me that “the people are living their daily lives, but nonetheless the company has full intention of entering, and wants to do so with distinct strategies like investing in highways, but there is a strong communal organization in the entire region and that is what’s preventing things—a permanent vigilance over the territory.” Highways are a classic play for mining settlement in the CSR model, but that has not weakened Nangali’s resolve. In the track “Rosa,” the speaker recounts her experience of resisting the CSR bribes. She says proudly:

They always told me that the mines would bring jobs, that I was poor and if I worked in the mine my kids would be professionals. I said no, my heart is so brave and strong, that I don’t care if my kids aren’t professionals, as long as they can breathe clean air. We would fight to the death.

Her voice fades into the sound of burbling water, holding together her determination to risk death, if need be, to fight for life, with the life being fought for.

The maxim of “water is life” became especially visible in 2017 during mobilizations at Standing Rock to protest the Dakota Access Pipeline. The construction of the crude oil transportation pipeline would contaminate the main water sources of the Standing Rock Sioux. It would also build over sacred burial grounds, calling to mind Walter Benjamin’s words in On the Concept of History: “Not even the dead will be safe from the enemy if he is victorious. And this enemy has not ceased to be victorious.” The sounds of water in “Rosa” then combine with strings and horns, evoking a baroque grandiosity over which the speaker’s voice can be faintly heard, looped and echoing. In reference to the ecological importance of the paramos, the refrain’s ghostly voice says, “This is where rivers are born, this is where rivers are born.” Life and water are again intertwined while the plaintive violin plays a melody that is both epic and mournful. The ghostly editing of the voice is unsettling; has the speaker died? Was the sound of water the victory of water as life, defended to the death? When the orchestra abruptly stops and the speaker’s normal voice returns, the ambiguity is deflated, and the possible undertones of sacrifice in the track are diffused.

This deflation is a wonderful expression of the narrative priorities of Suena Nangali. The tracks contain danger and death as a subtext and threat, but not as a primary protagonist in their mapping of territory defense. The protagonists are the speakers who have survived and resisted the danger and who continue to survive it every day. CSR is just one side of what mining interests will do to preserve their control and profits in an area. Territory defenders across the world have been strategically assassinated, criminalized, and tortured by police supporting mining companies. In 2005, police and private security in Piura kidnapped and tortured thirty-two campesinos (killing one) that opposed the same Rio Blanco Copper Mine attempting to overtake Nangali. Yet Suena Nangali is not a project of memorialization, although such tragedies require their due memorialization and mourning. Rather, it consistently oscillates between life and death to demonstrate both the stakes and the potency of political organizing.

The track “Que Suene Sin Mineria” closes out Suena Nangali on a note of hope and power. The title is aspirational, setting an intention with a hint of incantation: “let it sound without mining” or “may it sound without mining.” It is a desire for future sonic cartographies to be able to be free from the sounds of mining, with all the sounds of the paramos and Nangali loudly proclaiming sovereignty against the silence of a defeated mining project. There is not just one speaker in “Que Suene Sin Mineria,” but rather a chorus chanting different phrases that are looped over the sounds of birds squawking and the buzzing of insects. “Fucking government, cursed government,” they chant for the first few minutes after the sound of running water introduce the track. They then chant, “without a mine, without a mine, without a mine,” which appears to be a fragment of a longer chant yet contains the essence of radical anti-extractivist demands: to be without a mine. Not a socially responsible mine, not a mine of job opportunities, not a mine that postures as concerned about ecological impact, just simply to be without a mine.

Ivanna Berrios is a PhD student in Comparative Literature at UCLA. Their research centers on contemporary Latin American art and poetry, land defense social movements, and the political economy of natural resource extraction.

This post may contain affiliate links.