“You eat shit or down you go.” Someone in a Brecht play said that, I think, before singing a song about how horrible love is in a time of endless, fatiguing war. BTTM FDRS by Ezra Claytan Daniels and Ben Passmore takes us through the metaphorical and literal variations on that theme in a world where, divided by race and class, metaphorical doo doo chasers (if you prefer George Clinton to Mother Courage) run smack into the kind of creature that might really eat shit for breakfast.

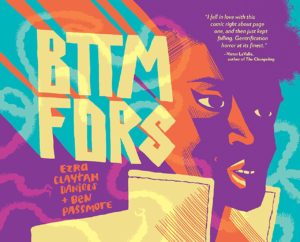

The Bottom Yards, where the story is set, is a fictional Chicago neighborhood, with all the markers of neglect and poverty that signify danger to the kind of people that don’t live there. In the 1990s, the only visitors might have been wide-eyed white anthropologists chasing new urban folktales (Passmore is able to work in a nod to Candyman). In 2019, the adventurers are more racially diverse but decidedly well off: high-concept artists and musicians, bankrolled by wealthy parents. In this gentrification-horror comic, the object of our attention is property: a mysterious building made immediately gruesome and the new home of aspiring fashion designer Darla.

Darla is in fact returning to her roots. African American and with a desire to trace her father’s path back to his childhood home (against his advice), Darla makes the claim to belonging in the new residence, even as young artists like her fuel the landlord’s ability to raise rents and displace the people who call the Bottom home. Positioned against her equally well-off white best friend, Cynthia, a sort of scenester with money but not even Darla’s ambition, Darla holds out hope for an authentic relation to the community while making money off the cache of style found deposited over decades of poverty-informed innovation in the Bottom Yards. For the arriving designer, the neighborhood is a seemingly untapped natural resource. If it wasn’t clear, she calls her line of bricolaged, souvenir-shop threads BTTM FDRS. One wonders what kind of blood-curdling monster story might have come out of CLTR VLTR.

As Darla attempts to settle into her new environs with the presence, if not exactly aid, of her self-absorbed co-gentrifier Cynthia, she discovers odd and unsettling features of the industrial site-turned-apartment complex. Creepy writing inside bathroom cabinets, intimidating figures stalking the halls, intermittent power outages, and the sudden materialization of oddly hairy coaxial cables.

Most striking about BTTM FDRS is the illustrator Ben Passmore’s use of flat coloring, with which he is able to create the drama and tension needed for horror. Constraining himself to just one or two colors (I want to say that the colors themselves are exciting and characteristically distinct), Passmore trains your eye toward objects and apertures. An entire room is an indiscriminate yellow, but the doorway is green. We get immediately the uncomfortable brightness of our cheaper, fluorescent-lit apartments with its thick industrial-strength glossy painted walls against the dim whispering no-man’s-land of apartment complex hallways.

One of my favorite moments comes early in the narrative. Darla and Cynthia are drawn by a strange noise to Darla’s new bathroom. In three flat-yellow panels the women inch closer to the bathroom. In the fourth we can see a sliver of red creeping over the lid of the toilet. Then, their faces are cast all in red, reflecting, just an instant before the reader, the horror splashed across the opposite page: a globular red mess, emerging from a yellow toilet, yellow reinforced concrete fixture, yellow bathroom entirely. The contrast pops, or ‘glorps’ rather. And if that sounds gross, the rendering is cuter, or well, more conceptual at least.

The tonal contrasts generated by color make every new thing stand out, and with each development in the narrative, while you’re wondering if this red is red in the real world of the characters or a kind of conceptual red, you can really see the objects and shapes Passmore and Daniels want you to see. Once you’ve been trained to look for the contrast, of course, they have plenty of opportunity to hide things in the background. When one character, an older resident of the building on her way out, talks about her sister who “invented an artificial heart powered by nothing but urine,” you could almost overlook the comment for the visual dynamism of the scene. It is, in any case, a brilliant scheme for a horror book.

As the narrative tension builds, color, its reduction to pinpoint attention and explosion, scores the book emotionally. At times, Passmore’s colors break out kinetically into three or four shades and we get the visual sense of an argument, of differentiation, of conflict or the mental chaos of coming face to face with something incomprehensibly monstrous. At other times we see a figure illuminated in a flashlight’s circle with only a dim sense of something out there beyond the light.

BTTM FDRS as an object looks cool. Its near-neon colors make me think of city nightlife and graffiti (help me, I’m from the suburbs), but it also makes me think about the relation of the creators to the neighborhoods in which their story is set. Daniels was born in Sioux City but spent many years in Chicago. Passmore lives in New Orleans and his work can be seen on the site The Nib, where he frequently addresses issues of police brutality and racism. That’s good enough for me, but I am left wondering about the problem at the heart of the narrative.

Gentrifier-horror, as opposed to the horror of gentrification, seems to be about the desire to settle into a neighborhood that is not your own while controlling entirely your experience of it. Fear comes because that’s impossible — not to mention violent in its own right. How many times does Darla try to call the cops into the neighborhood? (They never come, even as her fears become both more absurd and more real.) To be in the neighborhood is a thrilling proposition, as long as you have a way out before you — your personhood, your distinction — are wholly absorbed by the place. But Daniels and Passmore ask another question, which comes not from the anxious mind of the arriviste artist-bohemian but from the place itself: what happens when you train me to eat shit and I start to get a taste for it?

M. Delmonico Connolly is a graduate student at the State University of New York at Buffalo. He writes and revises sentences about race and pop after the Civil Rights movement and is the author of the forthcoming chapbook, Ronnie Spector in Rock Gomorrah at Gold Line Press.

This post may contain affiliate links.