[Silver Sprocket; 2021]

It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single woman, independent and fun loving, must be in need of being placed in a story that recalibrates her to sobriety!

That is not just a reference to one of the most well-known openings in the history of fiction. It is also a comment on how stories imagine different plots of fun for male and female characters. Indeed, fun seems to have a lot to do with gender. A fun guy, a man-child, is not hard to find: He has been around in quite a lot of cultural representations. For instance, we see him coming of age in the bildungsroman novel. We spot him in representations of men who avoid true love and declare that love that comes with an emotional baggage is not for them. A fun girl, on the other hand, is tough to define. She might make an appearance every now and then as a free-spirited woman who needs to be reined in at the end. Jane Austen’s Elizabeth and Emma are classic examples of these figures: adventurous, beautiful, carefree, and making decisions that scandalize those around them. But these women—including the women in Nora Ephron films like 1988’s You’ve Got Mail (which is based on Pride and Prejudice) and the 2007 Bollywood rom-com Jab We Met—eventually sober up once the story they are a part of turns a mirror to them to help them see their follies.

Elizabeth Pich upends this narrative structure and expectation in her comic Fungirl. It is about a nameless girl—or “Fungirl” is enough for a name and a type—who seems strange in the sense that she is non-confirming to traditional notions of girlhood. She is broke, unemployed, and even messes up the one job she manages to get in the story. There is no clear indication of the time and the place that the story is set in—another indication that Fungirl is a type rather than a particular person or character. She seems to be in her mid-twenties, given that she has a friend who has a career. But nothing much about her family or her past comes alive as concrete details. She also attracts accidents: Things keep going berserk, a pizza gets burned, a corpse catches fire, a kiss messes up a relationship. The list is really long. The events unfold not towards resolution but towards disasters, one after the other. The interesting, refreshing part is that none of it makes the story tragic or sends it on a re-routing, self-correcting mode for the girl to come to her senses.

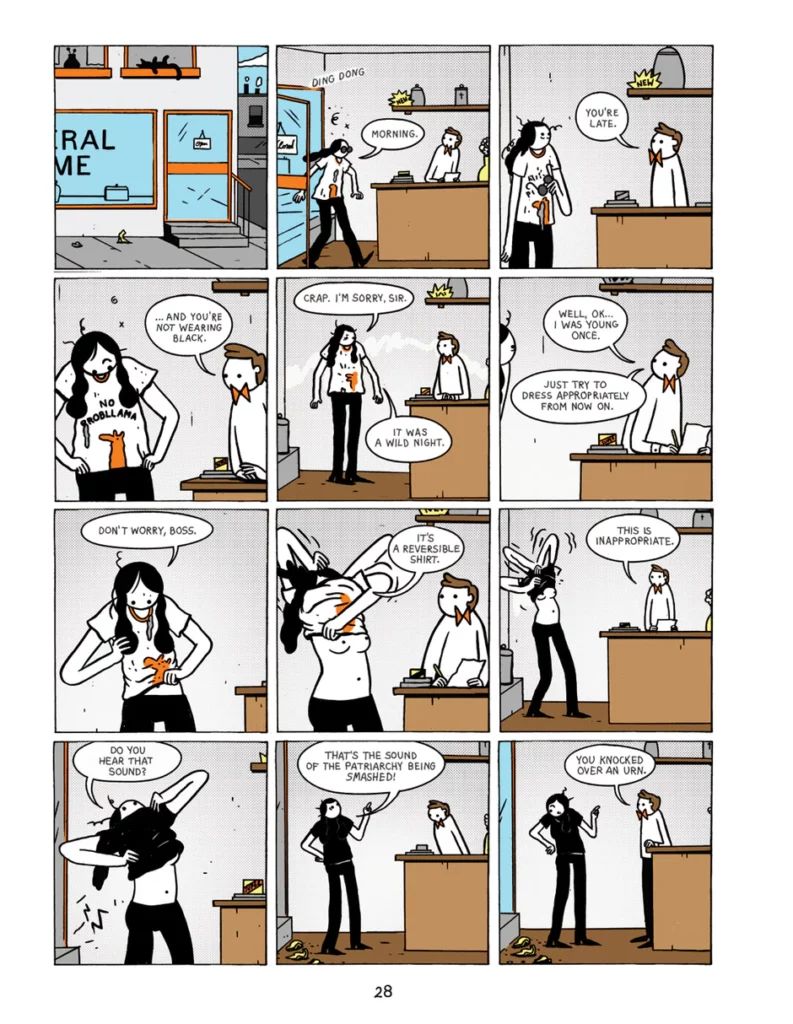

The story opens with her flying around naked and happy until she runs into a volcano. It turns out to be a dream about masturbation that she is jolted out of because of the smoke from a burning pizza. Thus, two pages into the narrative, readers know that it’s going to be a funride. They have met someone who is going to smash every notion of poise and propriety as feminine virtues and serve one misadventure after another. Pich does all of it with a laugh-out-loud energy: Because Fungirl does not care for distinctions between what is appropriate and what is not, especially when in company, she doesn’t even blink before taking her t-shirt off. She ends up burning a corpse she is supposed to get ready for burial. She loses her hard-begged-for doughnut to an accident. The accidents go on and on.

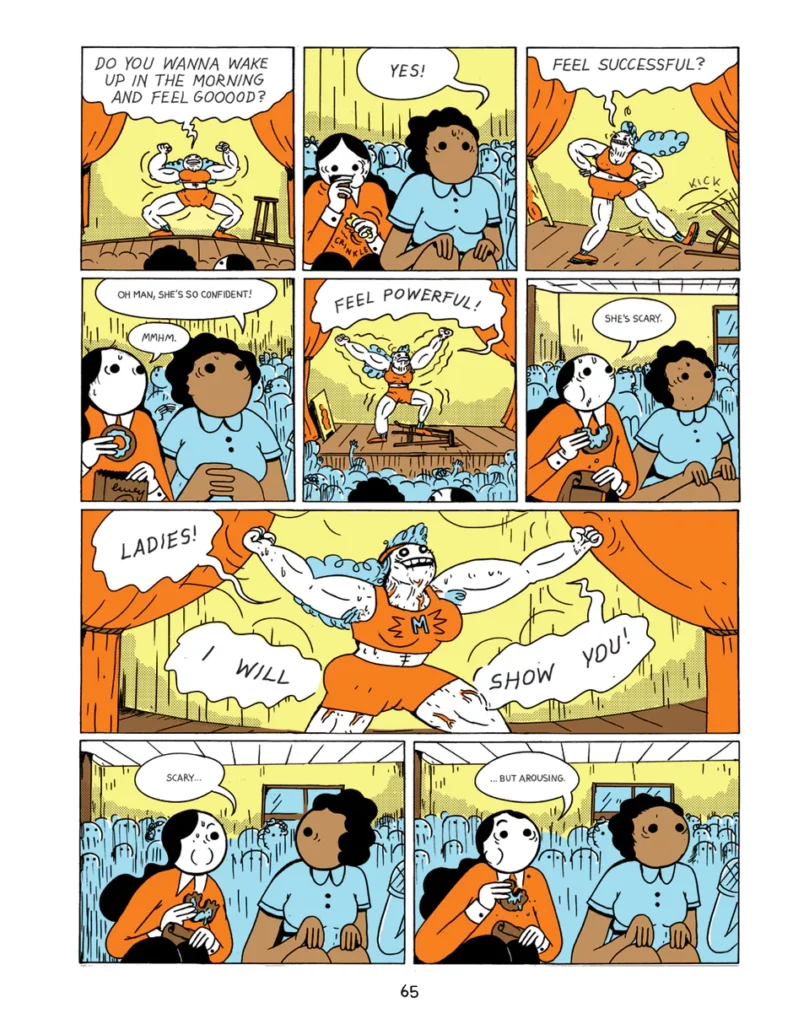

But all of it is done with remarkable empathy. Fungirl may be oblivious of the consequences of her actions and slips of tongue that set in motion chaos. But she is not insensitive. She knows how to console others. One brilliant piece of wisdom she offers to another character is: “Just because a relationship ends, it doesn’t mean it sucked.” She is fun and in contrast with other characters such as her friend Becky. Becky is the uptight, no-fun type, who is constantly stressed, is ambitious but gets thwarted by male colleagues, is in a not-so-hot relationship but puts up with it anyway. She wants to have it all, and is frustrated that she cannot. She is the archetypal modern woman who must have it all and work really hard towards it. In contrast, Fungirl is always thinking about “banging people,” looking for “fuckable people” at parties, and thinks of masturbation as a hobby. One motivational speaker calls her a “deadbeat with no ambition or direction in life.” Fungirl doesn’t care: “Wholesome” is “nauseating.”

This carefree attitude makes Pich’s Fungirl hard to associate with a genre. Rom-com would be an apt category, but given the happy endings of marriage or mission-love-accomplished narratives that are crucial to the genre in literature and cinema, one must continue to think of something else. That something else has to be a space that is free of Hollywood’s tacky but seductive romanticism.

Pich’s art is neat: The panels are neatly arranged boxes, even where the focus is on the mess that Fungirl makes or falls into. The thuds and the accidents are quite a scene—evoking an “ouch” here or a “haha” there—but they do not disturb or distort a sense of order and simplicity in the narrative. They do not get unnecessarily, indulgently surreal, drawing attention to themselves as far-fetched expressions of the bizarre. This consistent, tidy panel style does good justice to the idea that Fungirl need not be seen as a rare species but as someone we could easily run into everyday if we only had the eyes to spot her. Her nakedness, her accidents, and her casual references to sex are visualized to feel normal. It is only through others’ responses to her that one realizes she is unusual. There is hardly any panel that tries to be clever in the sense of playing with the order in which the text can be read. That is, the sequence remains linear. It is an uncomplicated story presented in an uncomplicated form. Put simply, it’s fun: One does not have to look for inner or deeper layers of clever allusions and subversions.

The dialogues are minimal, as if there is no need to fill the space and the narrative with words. And while the physical hardback feels heavy, the silences make it easy and light to read. There is no torment, no overthinking, no navel-gazing.

Comic lovers and those with an interest in gender/art ought to read this quest-less depiction of fun with a girl at the center for its simplicity. It might help one acquire a fresh habit of reading, one that does not look forward to self-transformation from carefreeness to carefulness. It might be an insight into another aesthetic truth: That a carefree woman is not in need of any correction, that she is enough for herself.

Soni Wadhwa teaches English at SRM University, Andhra Pradesh, in India. She is a regular contributor to Asian Review of Books.

This post may contain affiliate links.