Chaun Webster is a poet and graphic designer living in Minneapolis whose work interrogates blackness and being as a way to interrogate the world. Webster’s debut book, GeNtry!fication: or the scene of the crime, was published by Noemi Press in 2018, and received the 2019 Minnesota Book Award for poetry.

Wail Song: or wading in the water at the end of the world was published in April 2023 by Black Ocean. Like GeNtry!fication, it’s a book-length project arising from deep investigations into history, this time looking at the apocalypse that is slavery, slavery’s ongoing afterlife—what Christina Sharpe calls the wake—and the New World blackness that was created as a result of that rupture. Using imagery of the whale, a mammal that left the land for the sea where it was and is hunted as soon as it rises to take breath, Webster asks who gets to be a being. That said, Wail Song is much more than this description, also touching on notions of time, experimenting with form, and reimagining a character from Moby-Dick.

I first read pages of Wail Song in manuscript form, but revisiting the finished book felt like a new experience, and I suspect that it will reveal still more on subsequent reads. This is due to the rigorous thinking behind the book and the reading that inspired that thinking, which is recorded in the generous notes at the end of the book. The publication of Wail Song was an opportunity to bring our conversations about poetry into a more formal setting. We spoke two weeks after the book was published and the conversation presented here is lightly edited for length and clarity.

Timothy Otte: I actually don’t want to start with writing right away. I’ll say for readers: We’re talking in mid-April, in North Minneapolis, and we just experienced the annual April winter storm that Minnesota gets. Rather than talk about winter, though, I want to start by asking what plans you may have for your garden this spring and summer. Any projects or any new plantings that you’re excited about?

Chaun Webster: You know, I love getting my hands on the soil. I love thinking and planning in the yard, and the way that that allows for me to involve especially our younger kids in that process of putting something in the ground and seeing it grow.

But this year—we do have things that we started. We’re focusing more on herbs and have certain things that we want to plant. That’ll be okra or edamame and some peppers, but a lot of things also that we’re allowing to just be, you know, more in the way of wild flowers and native plants. I don’t want to have as much involvement over the summer in the things that we end up doing, because we want to leave Minnesota for a little bit.

So this summer is a little different. I feel like the last few summers we’ve spent a lot of time in the garden and it’s been a huge investment, and if you really want to do it you have to kind of be around a lot, right. You have to be there to prune, if necessary, and to do all of this other labor, and this summer we just kinda wanna allow it to just be and to lay back.

So, I don’t know. Always a lot of beans. I really love beans. And those things, once you kind of get them going, are fairly simple.

I started with your garden because I think of your work as having sustenance very much at the heart. I mean food, but also breath and shelter and water. All of that is central to the way that I conceive of your work and the way that I conceive of you in community. So I’m wondering, to turn toward your work a little bit, has your relationship to community—and particularly this community in the Twin Cities, and North Minneapolis in particular—changed since the publication of GeNtry!fication in 2018?

Yeah, I think that’s a great question. A lot of things have changed. Even in the process of writing GeNtry!fication and the time it takes for something to have been written and then to be published, things evolve. I want to hold ideas reflexively; I don’t think in the same way as I thought when I wrote GeNtry!fication, which is not to say that I think everything is trash, or it’s not valuable. I think it’s very valuable and representative of my thinking at a point in time.

In writing GeNtry!fication—even though understanding that if I assumed or attempted to write something that I saw as an activist artifact, that that would not itself be something that could or would put an end to gentrification as a colonial and anti-black project. That artifact could only document a point in time. But a part of me maybe had more hope than I do at present in regards to what development could or would do. I think that there was maybe a part of me, latently, that thought that maybe there is some sense of equitable redevelopment, as some folks like to articulate it, and I think that development as a project now is one that’s always connected to a certain kind of extractive regime. And so those are different positions.

I still think a lot about space; I think a lot about like black spatiality. I think that’s represented in my writing with this latest book. But I think about resistance differently, and so I try to be very careful in how I think about terminology, especially when thinking about things like marronage. I think sometimes [that term] can be used too loosely. What does it mean when folks are gathered on a corner or at their porch and there’s a certain kind of black spatial practice? Does that black spatial practice mean marronage? Does it interrupt the various machinations of the anti-black world around them? I don’t think I would say that it does, and I think that there’s a historical materiality to using language and grammars like “marronage” that I was perhaps too loose with in my assessments in that project.

Now, as that relates to my relationship to North Minneapolis: like, we’re still here. I’m still trying every day to be present with those who I consider myself to be in conversation with, and to whom I consider myself to struggle with. But I think that is a long, hard ongoing project and work, you know? I don’t have a sense of what that means in the future. But, I mean, from 2018 to now, we’ve experienced a lot. We’ve experienced a global pandemic. There has been the murder of George Floyd by the hands of Derek Chauvin that is witnessed by the world, and I think, in the midst of all of the responses and reactions to that, I feel a bit disillusioned. Because I think there’s a way that the state of Minnesota and the city of Minneapolis is talked about outside of this place that doesn’t really have a careful and close attentiveness to what has happened here. I mean one that’s not, you know, ego based or thinking about what organization to put on a pedestal. I just don’t know necessarily that there’s been an accurate or careful assessment of what happened in 2020. I think there have been many really big statements about it that I don’t agree with on a number of angles. And I think that that’s challenging.

It’s challenging to be here and to feel like there’s no grammar for your politics here, that your politics are without representability. I don’t think I place that as a moral position, because I think it’s all types of things that are flawed and changing and shifting in my own politics. That’s a long and difficult response to your question.

I mean, it’s a big and difficult question to ask, so I think a long and difficult response makes sense.

You were talking about ideas of development and investment, and any time that that kind of thing comes up—and this goes back to my question about your garden—I always think about like, okay, who’s it for? And who’s doing the developing? And almost 100 percent of the time it’s not the community itself. So for me, keeping a garden and being in community in that way, being really present on a very atomized level, on the block, feels like the place for that kind of work. I’m more interested in the ways that my neighbors and I can develop our block by keeping different things in our gardens and sharing those things.

Yeah, and same. I don’t know necessarily that I would identify those things as development in the same way. Part of what I’m trying to say is that development itself is a colonial project. Development itself is wrapped up in, at its inception, a notion of coloniality, and is always thinking about a space as barren and needing to be in some ways shifted and changed, in a similar kind of fashion as you see Columbus coming to a land and looking at the “barrenness” of that land. So there’s an assumption of what is not present and then what one is bringing to a place.

So, like, nation building and world building in the West and in modernity required anti-blackness, which is an apocalyptic regime. It is a regime that is forged in the hulls of slave ships. It is something that is forged in the Caribbean and Americas, in terms of the plantations that are these labor camps that end up fully transforming the land and life in ways that, you know, we still are dealing with the ramifications of.

So I think that what’s shifted for me is that I thought prior of development as a tool that could be used in ways that were responsible and equitable. And what I’m saying now is that I don’t know necessarily, actually, I don’t think it is a tool that I can use responsibly and equitably. Because I see that it is itself a colonial and anti-black tool. So what does it mean if I come to certain conclusions like that? And I think again, and this will lead back to Wail Song, [which], as a project, was for me to say, I want to hold agnostically a set of like ideas together and pose some questions—ones that I don’t feel I have resolved—and move through the difficulty of them, and attempt to do so as honestly as I can manage. And that was a challenging thing to do, you know.

Yeah. So sticking with Wail Song, one of the things that this book does is talk about the ancestors of the whale as having given up on the land. And that feels related to this idea of giving up on this project of Western ideas of development and extractive labor. In that regard, do you see Wail Song as a kind of a Utopian pointing project?

Not at all. I think it is one that is perhaps working against much of a certain Utopian strain. Even as I look to folks like Jayna Brown and Black Utopias as an important point of conversation, as well as I think Kara Keeling’s work is an engagement with Utopia. Both have a certain grounding in [José Esteban] Muñoz’s work, which often is talked about when thinking about queer futurity, Cruising Utopia being a really important text.

But for Wail Song, a part of what I’m attempting to do is to say that we are in the afterlives of slavery, that is an ongoing terror. And if situated in something that I don’t see as a kind of teleological problem—that is, not a problem that has a beginning point and endpoint in the way that we would like to stamp a kind of teleology on slavery—but that it is a structural and paradigmatic issue. And so, if the question that I’m asking is ontological, and that is a part of the terror, then what does it mean to not know if there’s anything on the other side of the terror? How do you move through the space of the abyssal, as [Édouard] Glissant talks about, as Calvin Warren discusses, in ways that you don’t know if there is any other side?

A lot of Wail Song was starting with thinking about death [and] there were times in the text where I would talk about death as an event. And then, catching myself, would tell in the text, hey, I’m talking about this as an event again, so as to try to hold open the difficulty of a certain kind of thing. I’m trying to move through not knowing if there’s anything on the other side.

That’s something that’s against the kind of Utopian futurity or a gesture that has a belief in futurity. Because that belief would suggest a certain kind of hope for something beyond this. And what I’m saying is that I think that would be premature. What does an honest reckoning with this look like? From, in the case of Wail Song, an agnostic position that says, “I don’t know. Maybe there is something, but I’m not sure.” And to reckon with that honestly means that I have to situate myself here in a way that suspends a kind of hope or belief in a certain kind of futurity.

One of the things that Wail Song does so well is hold multiple positions at once and layer multiple ideas together, from the title on. You sent pages to me back in 2020, so I’ve been sitting with this work for basically three years, and as I was spending the last couple of weeks with this finished object, I kept thinking that this book holds the unknown and holds multiple positions at once better than any other poetry collection, any other book that I’ve encountered.

I don’t know that I have a question necessarily, or maybe the question is, Will you help me puzzle through? Is it—This is where I struggle: Is it doubling? Is it layering? Is it . . . tripling?

I’m puzzling through all of these dualities that exist in the text. The idea of birth and death being connected, the idea of breath and life, and their opposites, as we usually conceive of them. The book is making this argument that they’re not opposites. Birth and death are not necessarily opposites, breath and non-breath are not necessarily opposites.

Yeah, no, I mean, so to respond at least with that strain of thought: You have New World blackness emerging from the slave ship, as many in black studies identify. So if that is the origin of New World blackness, then the birth of blackness emerges in the space of death and deathliness.

Glissant calls the hold of the slave ship the “womb abyss.” He calls it a womb. Place of birth. But what is being birthed but death and deathliness? The assumption is death. If you look to the Zong—the Zong was a slave ship, which M. NourbeSe Philip writes about—it has this cargo/enslaved Africans who are aboard, who are both jumping but also thrown overboard. And the slave holders of that ship were not able to retrieve the claim on insurance if [the slave] died a “natural death.” M. NourbeSe Philip challenges that language and talks about, How could there have been a natural death under those conditions? There’s a contradiction there. She suspends our assumption of a presumed naturalness to the death. There’s something very unnatural about it all.

But also the insurance claim. Ian Baucom writes about how insurance operates with this understanding that I have to imagine destruction, I have to imagine ruin. So the ruins are already there, the destruction is already there.

Part of what I’m working through is the sense of there being always the ruins, always the death and deathliness in the space and time of New World blackness. If this is a world building regime, it’s an inaugural regime to the modern world as I know it. Fundamentally, that shapes everything. It shapes our notions of property, citizenship, place, and financialization. The very notion of who is actually a being is a part of what that project is wrapped up in. And if that’s the case, then birth isn’t necessarily doubling as death or that these things are opposites, it’s that there is perhaps an impossibility to a consideration of life and death. What does it mean if one is not considered to be among the living?

A claim that Sharon Patricia Holland makes in Raising the Dead is that there are some who are not considered to be among the living at all. So if the black subject is not among the living then there is perhaps, as you’re saying, a kind of doubling that’s happening, but that doubling is a doubling of death, and perhaps there’s a death that happens post-mortem. What does it mean for someone like Derek Chauvin to already have assumed the death of George Floyd prior to it happening in our understanding of it as an event? That’s maybe part of an example of what that would mean. There is an assumption already that there are those who are already without life, as we understand it to be constituted.

Wail Song is wading in that. What does it mean to move in that space, to be subjected to that terror? Well, for the whale, which was and is hunted when it emerges from the water, once it takes breath, for the whale and its ancestors, a part of what that may have meant in evolution is that it decided that the land was no longer the most reasonable place to be. It didn’t make sense. The conditions were not optimal. The conditions were better for the whale in the water.

Parallel to that, I’m asking questions about what are the conditions and places for which there’s an optimal level of potential ongoingness or survival for black people. Dionne Brand says, “I don’t want no fucking country.” She doesn’t see there to be a place within the nation or the land as a space of safety. So I am reckoning with that, and maybe some of that is a placing together of some sorts of opposites, but also not.

Well, you said a couple of things—suspension is in there, parallel—which feel related to things like beginnings, endings, layerings—that is what I’m puzzling through. It’s not just opposites or juxtapositions, but also mirrors, loops, and so on. You write in Wail Song—I wanna make sure I get it right, but I don’t remember what page it’s on—that blackness is in the water—

“Blackness isn’t just in the water. It is the water.” Page 61.

Thank you. And maybe my challenge is that the pattern of my thinking and my poetic education has been to look for those kinds of binaries that Wail Song is pushing against. It’s the kind of text that I need to return to, and not in a linear way necessarily. That brings me to the idea of notes and citations and how central that is to your work, both in GeNtry!fication and in Wail Song. Engaging in the cited texts is also a way of reading your books.

I think we’re really invested in notions of the individual as the progenitor of, like, a novel set of ideas. I don’t think there is necessarily something terribly novel about what I’m discussing in Wail Song. I’m just trying to bring together a set of ideas from a number of other spaces, right? I’m trying to take folks through a session of my study, which was for a period of like three years.

I’m sitting with all of these various kinds of texts, whether those texts be Saidiya Hartman’s Scenes of Subjection, or Christina Sharpe’s In the Wake, and I’m trying to have a conversation around what I see those text’s implications to be with regard to these things I’m wanting to write on. I think being open-handed about that is not always something that every writer is taught to do. I think that that’s actually kind of against the grain, in some respects. There is a citational practice that’s taught for folks in academia, [but] I don’t know necessarily that it’s always as apparent in poetry. It’s not always necessary. I don’t think of citations as, oh, I need to be invested in a kind of academic rigor, as much as I think of citations as, I need to place myself within a tradition and conversation.

I’m always trying to honor my attempt at being within and part of a tradition. It’s to say that this is not possible without the work of Hortense Spillers, without the work of Alexis Pauline Gumbs. It’s not possible to think about these things, at least in my own study, without Sharon Patricia Holland. All of these thinkers are a part of the extended consideration that I have in Wail Song. There is the opportunity, as a reader, to come to how I have walked through those texts. And so as a reader, you are invited into engaging with Sharon Patricia Holland’s Raising the Dead, you are invited to engage with the work of so many others who informed the writing in Wail Song.

I try not to do that in a way that steps away from the pleasure I have in the lyric, because I think there is a way to engage in academic writing and poetry, or to engage in theoretical ideas in poetry, that can move away from the lyric that I’m not as interested in. Which is not to say one is better or worse. I’m invested in a certain pleasure that I receive in the sonic. I love coming to a text for its sonic quality, and so I think that’s something that I at least attempted to hold onto.

Because it’s hard to write about. How do you write about and engage with Calvin Warren’s Ontological Terror as a dense text and bring that into conversation with what you’re writing on being and blackness and whales in a book of poetry? And have that still hold some kind of lyric quality? I don’t know that I achieve that in any perfect sense. It’s a hard thing to do.

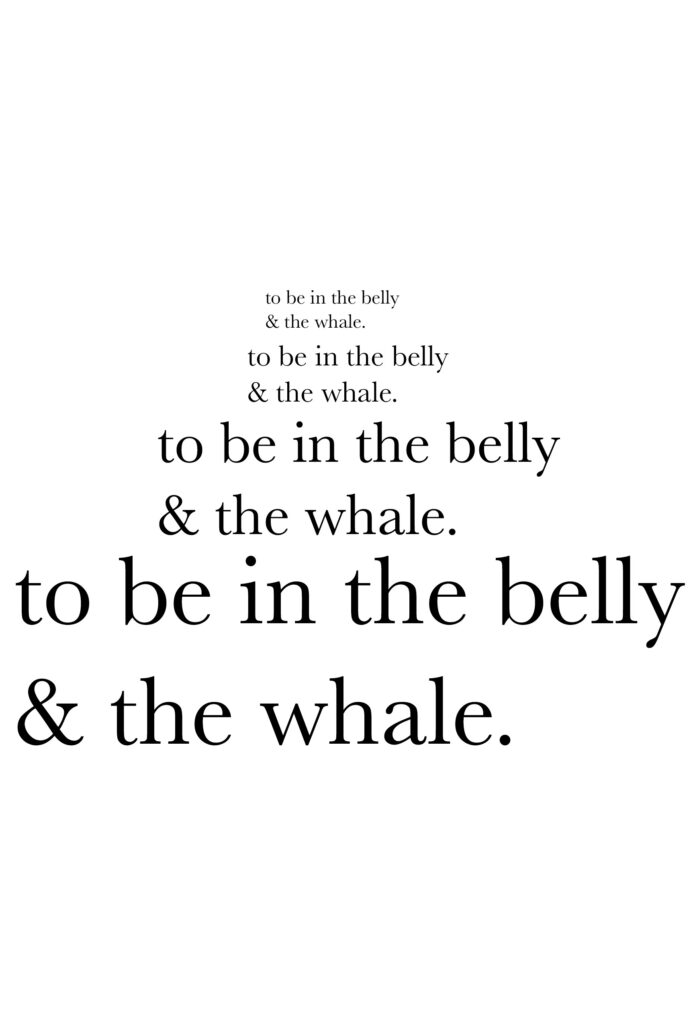

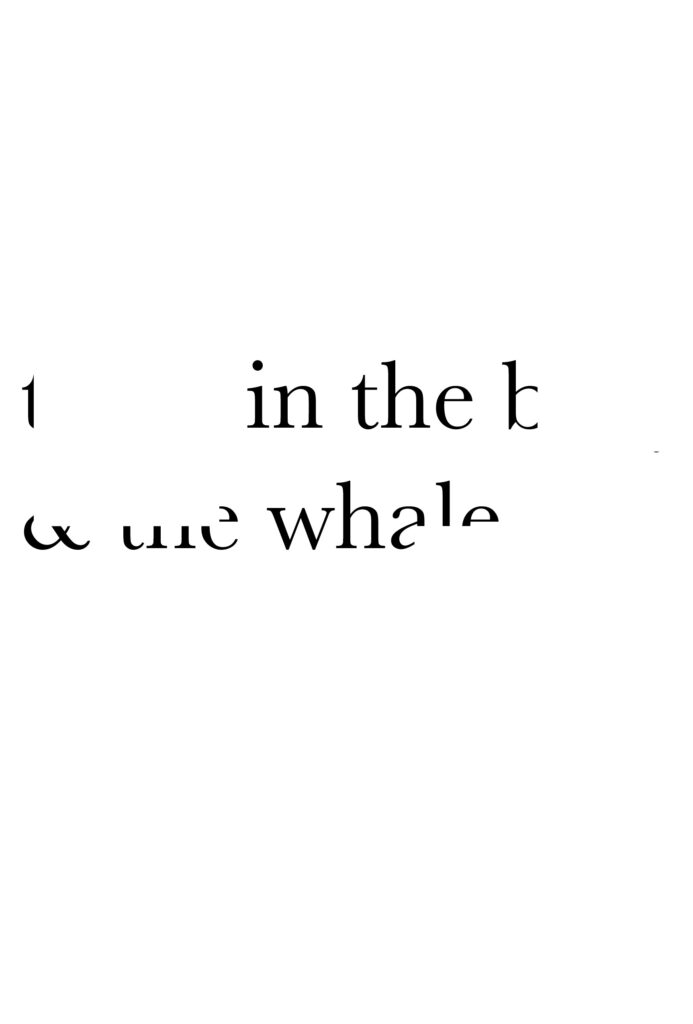

Can we talk a little bit about craft? Your work engages in concrete poetry and visual poetics, but I think in Wail Song it’s a little more subtle. But also in Wail Song, there’s more engagement in received forms. I was thinking a lot about the prose poem in the tradition of Alexis Pauline Gumbs, of Dionne Brand. Especially in these modified ghazals I was hearing a lot of Nathaniel Mackey. Was it a conscious choice for you to move more towards those received forms in this book?

Yeah, I think with [the ghazal] I was really interested in it in terms of its repetition. I was interested in it in terms of trying to think about each of those couplets as a unit of time and think about them palimpsestically. How is it that this time is building on itself and looping? That was my fascination with that form, and definitely with those folks that you’re naming. Dionne Brand, Alexis Pauline Gumbs, Nathaniel Mackey all have this incredible, lyric sensibility in their work. They’re models of a sense of song, of ongoingness. Nathaniel Mackey’s work is a kind of measure, and Dionne Brand as well. I look to them as exemplars of being able to engage with a certain degree of formal exploration in the line, in the line break, and in the use of older forms and invented forms. Alexis Pauline Gumbs is a huge example for me in how to hold onto an extended engagement with a single text or like a set of texts from a single writer.

I don’t know necessarily that there are methodological things I can pinpoint here as far as, okay, what does that mean for me on a craft level, as much as I know that these are texts that I’ve returned to again and again and try to metabolize. I was only writing Wail Song in a focused way for a period of like three months. It happened incredibly quickly, but the reading, the study for Wail Song was like three years.

As far as the craft level, there are certain things—for instance, thinking about Pip and those sets of movie pitches as movie pitches, I was wanting to think about the filmic nature of the scenes of violence that we’re constantly consuming and what that does in its repetition as a kind of ongoing reel. Pip in Moby-Dick is thrown from the Pequod, he doesn’t jump. In Wail Song, Pip jumps from the Pequod in every instance. I’m wanting to take a particular mythic position and reimagine, in a speculative manner, a different gesture with Pip. Maybe that’s about as hopeful as I get in Wail Song, if I would even call it that.

Sticking with craft, I want to end on this idea: on page 22 there’s this phrase “an assemblage” that’s used several times. You just mentioned that the writing of Wail Song was a period of study followed by a pretty intense period of composition. I hesitate to ask this a little bit, only because the book really disavows this sense of linear time, but was there a moment either in your study or as you started writing that you felt like, oh, maybe there’s something here, maybe this is the seed that will turn into a text?

I think there were many moments. I got asked to write a piece for an online platform, and I think that initially, they were asking me to respond to the murder of George Floyd, or if I had any desire to respond to that. And I didn’t, really. But I did want to think about, in an extended way, breath and breathing.

I was doing that through thinking on how our fourth child, Ocean, was a water birth, and as a water birth, how—right before she was coming out into the world, so to speak—that the doctors [and] midwives were saying, don’t be concerned if your child is emerging fully submerged because often it’ll take them a moment to begin breathing, so don’t be alarmed. Which is an alarming thing to hear, even! But that was the case. Ocean was fully submerged when born and took an extended period to breathe. And I felt that in a very visceral way and wanted to stay there in my writing, to stay in that extended period in which she was without breathing or had a paused breath. That was maybe a turning point.

The second part of the book is two essays that are wrapped in with each other. One is thinking on the birth of my child; another is an engagement with an archive. I read in Stephanie Smallwood’s Saltwater Slavery [about] a woman aboard the James, a slave ship, and they are with child, and the Dead Book, which records the mortality aboard the James, says that that child was dead within the womb, and that they also were dead two days after they were born. So there’s this kind of double articulation [of death] happening in that text, and either an assumed death that happened in the womb, or there’s the potentiality that the child had forty-eight hours in which they were breathing. I wanted to think about, what does it look like to be in the speculative position of forty-eight hours of breath for this child aboard the James.

Both of those things—both the invitation to write in certain spaces that allowed the opportunity to think on something in an extended fashion, as well as thinking about how certain things might be in conversation with each other—were transformative moments of assemblage in Wail Song, Assemblage is very much a part of my process. I’m constantly looking over a broad expanse of ideas and thinkers and pulling things from all of those spaces in ways that are a part of my own intentions and objectives around a project. Sometimes that works, and in cases of what I’m trying to write now, not in every sense is that the way to go about it, as I’m learning. There are projects, like what I’m working on now, that are informed by this work, but are starting from a very different position, and require something very different from me.

But for [Wail Song] that sort of assemblage worked well and was something that allowed me to come in and come out and hold on to something and to build a thread and to see it through. I had to do a lot of note taking, and I had to ask people along the way, yourself included—I had to get other sets of eyes on it, because I was deep in it. You don’t necessarily want to do that too early, but at certain critical points in the work I was really needing to have other people comment on it and see it. I myself couldn’t helicopter up from it.

Doug [Kearney] brought me into a conversation with LaTasha Nevada Diggs, and that reading was huge for me. Certain people that I hold a really deep level of admiration for were in that space and reached out and said, “Hey, stick with that.” I had at that time maybe two pages of Wail Song and read from those as a part of that reading. Those moments and invitations were the necessary sparks to say, I have all of the study gathered, I just need to sit and write it.

Timothy Otte is the author of the chapbook Rebound, Restart, Renew, Rebuild, Rejoice (Lithic Press, 2019), a mentor with the Minnesota Prison Writing Workshop, and writer of a newsletter called Stanza Break about poetry in translation and books outside of a publicity cycle. Otte lives in Minneapolis and works as a children’s bookseller. Say his last name like body. More at timothyotte.com.

This post may contain affiliate links.