The following piece is excerpted from an article in White Fungus, an arts and culture magazine based in Taiwan. In “Wasteland Utopia,” Taipei curator and music writer Jeph Lo describes witnessing the emergence of noise music in Taiwan following the lifting of martial law in 1987. The 1990s in Taiwan was a chaotic time of street protests and burgeoning counter-cultural activity, as the island transitioned towards democracy. It was in this period that Taiwanese noise music emerged. For more information about White Fungus and to order a copy of the issue, visit whitefungus.com.

The “Wild Lily Movement” of 1990 was a catalytic event of symbolic importance for the development of noise in Taiwan. This demonstration for direct democracy took place at Chiang Kai-Shek Memorial Hall Square [since re-dedicated as Liberty Square], occurring at a time when the reverberations of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests were still in the air. From March 16th to the 22nd, thousands of Taiwanese students and professors gathered in the square, in front of the National Concert Hall, where events continued as usual.

On one afternoon, a string quartet was preparing to perform in the hall. To boost morale and show support for the protestors, the group came out to play a piece of classical music between speeches. But before the music had ended, a student rushed onto the stage, grabbed the microphone and shouted that this kind of bourgeois music had no place within the movement. The four musicians took their instruments in a panic and fled.

So what was the music of the movement? The protesters sang songs that were banned under martial law; they preferred music that had been forbidden or was not easy to hear. Classical music, with its lofty status, was rejected. If the sounds rejected by mainstream society are ‘noise’, and the sounds accepted, ‘music’, then we can see how, in the course of this movement, the status of noise and music was inverted.

A giant balloon puppet featred in the Taipei Breaking Sky Festival, 1994. Image courtesy of Yao Jui-Chung.

During the Wild Lily Movement, two members of the group Blacklist Studio led the crowd in writing lyrics to a song. They then recorded it at their home studio, in a single day, before returning to the plaza to distribute hundreds of cassettes of the recording to the crowd. Blacklist Studio’s disjunctive music style — incorporating Taiwanese folk, rap and rock, with vocals in Taiwanese, Mandarin, Japanese and English — was pointedly different to the kitsch pop music dominant in Taiwan, produced through the star system of the major record labels. Prior to this movement, the group had played a key role in forming the popular genre known as “New Taiwanese Song,” which dealt critically and frankly with Taiwan’s political and social reality.

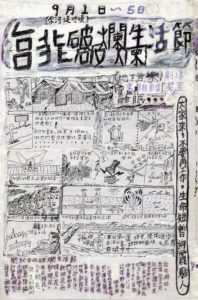

In 1995, thousands of people attended a three-day outdoor festival in the ruins of a Banqiao distillery. The Taipei International Post-Industrial Arts Festival featured some of the most notorious Taiwanese and international noise groups of that time. Today, when people think back on this festival, they remember the scorching hot weather, the hissing, the flames, the violence, the stench, the abrasive noise and bodily senses: Moslar Theater rolling naked in mucus; Schimpfluch- Gruppe, from Switzerland, roaring with microphones in their mouths and provocatively confronting journalists; Con-Dom, from the UK, walking off stage and sexually assaulting members of the audience until met with violent resistance; Loh Tsui Kweh Commune (LTK Commune) acting out rape on a mannequin and performing arson; Zero and Sound Liberation Organization (Z.S.L.O.) tossing around a bucket of filthy kitchen waste, with the fetid odor of rotting food causing Japanese group C.C.C.C. to refuse to perform. There was almost no occasion in which the word ‘beautiful’ could have been used to describe these performances [thus complicating the notion of liberation].

A booklet from the Taipei INternational Post-Industrial Arts Festival, 1995. Image courtesy of Lin Chi-Wei.

In the current environment, noise is still not recognized by the Taiwanese mainstream as an acceptable or cultured form of art. If the Post-Industrial Arts Festival were held today, we can easily imagine its reception in the gossip columns of the tabloid

media, littered with sensational headlines. The people involved in the event would no doubt be attacked with a barrage of slander by outraged netizens and television presenters. The civil servants associated with the event would likely be punished. In fact, the festival at that time was reported on by a number of major arts publications, and the event was even sponsored by the Taipei County Cultural Center.

This is not to say that Taiwan’s acceptance of avant-garde art has regressed, nor to infer that things aren’t as good as they used to be. The point is that, in 1995, these musical offerings that challenged the system and aggressively violated the social order were able to avoid moral accusations, and the festival was only criticized on aesthetic grounds [despite the acts of sexual assault by Con-Dom]. A principal reason for this was the rupture in governance and complete overhaul of Taiwanese society that occured as the state transitioned from protective authoritarianism to democracy and embraced global capitalism. People were able to tolerate the festival, even if they didn’t accept it. If a house has caught on fire, why bother about a few scattered bottles and cans left in the room as it burns?

To give a fuller picture of the charged atmosphere in the first years following martial law, I’ll refer to a few incidents:

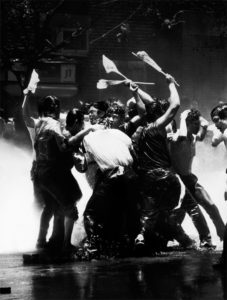

On May 20th, 1988, thousands of farmers from across the country amass in Taipei to protest the government’s authoritarian grip on the agricultural industry. Known as the “520 Farmers Protest,” it is the first major clash between civilians and police in the post–martial law era, and one of Taiwan’s bloodiest days since the “228 Massacre” of 1947. Violent skirmishes continue unabated for nearly 20 hours, with protestors throwing sticks and stones at police, and lighting fires in the streets.

Then, in May 1990, the President nominates former soldier and defense minister Hau Pei-Tsun as Premier of the ROC, igniting people’s fears of a return to military rule. In the midst of one of the ensuing street protests, a molotov cocktail is launched in the direction of riot police — the first instance of such an occurrence in the history of Taiwan’s protest movements.

In the month leading up to the Post-Industrial Arts Festival, a traffic accident sparks a civilian conflict known as the “Taxi Riot Incident.” Dozens of drivers from two of Taipei’s taxi companies clash in what might be described as all-out street warfare. Wooden clubs and molotov cocktails are wielded by both sides; cars are smashed and burned. As Taiwan emerges from the silence of its martial law period, it’s clear that the country’s governmental mechanisms are unable to deal with the eruption of agitated voices.

A flyer from the Taipei Broken Life Festival, drwn by Wu Chung-Wei, 1994. Image courtesy of Yao Jui-Chung.

It’s easy, now, to forget the social atmosphere of the martial law period. It was a time laden with all kinds of restrictions. Civilians’ daily lives were subject to numerous checks and prohibitions — right down to bans on certain hairstyles. Men with long hair were forced by the police to shave their heads. A girl’s hair could be no longer than her earlobes. There were also bans on public performances of Taiwanese music and theatre; dance halls were made illegal. Songs, publications and even ideas were censored. This system of surveillance and inspection had a deep, lasting impact on all aspects of people’s lives.

In the late 1970s, amidst the island’s thriving folk song movement, singer and television host Yang Tzu-Chun’s self-titled album was banned, due to the ‘left-wing’ social consciousness in her lyrics. In 1978, Yang organized the Grass Field Charity Concert, which attracted upwards of four thousand people — at that time the largest outdoor festival held in post-war Taiwan. Whilst Yang’s goal for this event was to raise funds for a charity with no expressed political agenda, due to her massive appeal, the festival was still monitored by the intelligence agencies of the KMT (“Chinese Nationalist Party”). Her later concerts were all subject to bans and harassment. Eventually, she gave up music altogether and focused instead on the political opposition movement.

Metaphorically speaking, martial law built high walls, blocking the creation of art and culture and separating people from all kinds of possibilities. It turned regulated zones into areas of wasteland: media, spatial, corporeal and ideological. After martial law was lifted, did these walls collapse like the Berlin Wall? We can’t truly say that they have all fallen. The guards may have left, but the walls remain. Taiwan was under martial law for more than 38 years. Over such a long stretch of time, it became engrained in the consciousness of most people. So in toppling these high walls and breaking into the ruins, even without the threat of imprisonment, people still needed to be courageous. They had to overcome the secret police in their own and others’ heads.

Wang Fujui performing at the White Fungus issue 12 release event, Taipei Contemporary Art Center, 2011. Photo: Etang Chen.

But nearly four decades of repression under military rule actually generated ample energy within Taiwanese society to escape this oppressive consciousness. This powerful and intense energy was encapsulated in a saying popular among intellectuals of that time: “Subvert the System.” In facing this kind of hidden atmosphere, the government didn’t know whether to attack or retreat, leading to the rise of the aforementioned movements and struggles.

I will draw from my personal experience to shed more light on this phenomenon. In 1994, I attended the Broken Life Festival, which was the precursor to the Post-Industrial Arts Festival and Taiwan’s first music festival to be held over consecutive days. The main organizer of both events was Wu Chung-Wei. Without approval from the authorities, Wu occupied wasteland by the river in Gongguan, Taipei, where he used stolen and collected materials and equipment to erect tents and a stage, constructing the festival site out of salvaged junk. The performances staged there were raw and reckless; the atmosphere was anarchic, like a collective trampling over taboos. On the second night I remember seeing a police car patrolling the site of this illegal gathering. After stepping out of his vehicle, the officer was surrounded by the crowd and ridiculed. From my position, about ten meters back into the crowd, it looked as though he was being pushed around. The officer didn’t know how to handle the situation. All he could do was resentfully get back into his car and leave, driven away by the crowd.

The most important facet of the noise movement’s spirit was that it not only enabled a handful of artists, but, moreover, it helped unleash the power of congregation. But even with enough gunpowder, an explosion still demands a fuse and a spark. That was the role of artists.

Jeph Lo is co-director of Taipei project space The Cube. He has written extensively and curated exhibitions about Taiwan’s sound cultures.

This post may contain affiliate links.