Chicago-based rapper Serengeti

This essay first appeared in the Full Stop Quarterly, Issue #8. To help us continue to pay our writers, please consider subscribing.

It is more than just the name. At the start of rap, it was about stepping into a phone booth and coming out as something greater than you were.

—Hanif Abdurraqib, “Ric Flair, Best Rapper Alive”

Personas tend toward exaggeration. This is the “coming out as something greater” that Hanif Abdurraqib describes in his essay on the similarities between rap personas and that of the wrestler Ric Flair. People don’t often choose to become less than they actually are, but what would an understated persona look like? If someone can, like superman, just step into a phone booth to don a new name and a new image, their change does not necessarily require becoming “something greater.” In contrast to the glitz, glamour, and braggadocio of exaggerated personas like Ric Flair, rap personas might also explore issues of normalcy, realism, and authenticity.

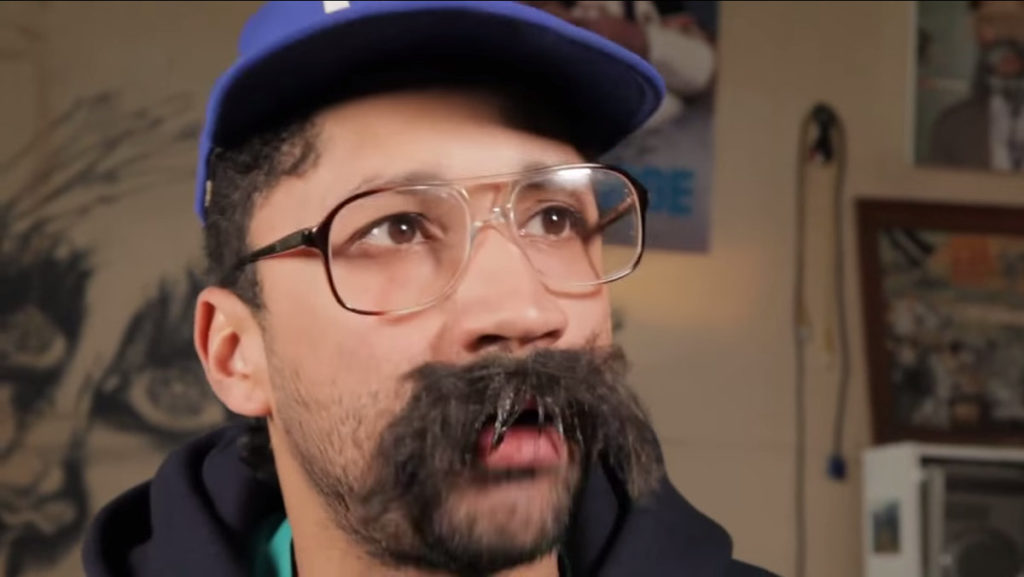

David Cohn, who raps as “Serengeti,” has explored these two tendencies—exaggeration and mundane realism—throughout his career, starting with his rap moniker. While “Serengeti” refers to the massive geographical region in Africa, which spans more than twelve thousand miles, the personas through which he raps are understated, seemingly minor characters. Over the course of a discography spanning more than twenty albums and EPs, which range from collaborations with Sufjan Stevens and Open Mike Eagle to vinyl records cut by hand with a lathe, Cohn has always been attuned to the ephemerality of fame, personas, projects, and careers.

Eight of Cohn’s albums follow the life of “Kenny Dennis,” a native Chicagoan, through his career as part of the old school rap group Tha Grimm Teachaz, to his middle age, the revival of his rap career with the hip-house duo Perfecto, and his relationship with his wife Jueles, who has a music career of her own. In Cohn’s voice, Kenny works out two opposite desires, the one tending toward comfort and acceptance of what you have, and the other toward desire for glory, fame, and exaggeration. Kenny Dennis is an expression of hope that life can be normal, and that’s okay. Ironically, the most overblown characters are a way to put faith in commonality, ordinariness, and a life that is merely enough to fulfill you. Put differently, it’s a hope that utopia can be banal. But Cohn’s experimentations with performativity (the proliferation of an imaginary musical and social landscape through the creation of whole albums by Kenny and his fictional collaborators) and meta-fictionality (the self-reflexive act of rapping in the persona of a rapper exploring persona) reveals Cohn’s doubts about this hope’s durability. If Kenny finds a way to live in a sort of utopian normalcy, he can only do so through an increasingly fragile construction of irony, performativity, and meta-fictionality.

“Favorite Actor: Dennehy”

You know exactly who Kenny Dennis is as soon as you hear him rap. This aging Chicago native has a big pair of glasses and an even larger mustache. He will also tell you all about his favorite things on the title track of Serengeti’s 2006 album Dennehy. In a thick, put-on Chicago accent, Cohn introduces Kenny through a barrage of details that are remarkable only in their unremarkability:

Favorite actor: Dennehy

Favorite drink: O’Doul’s

Bears, Hawks, Sox, Bulls

This is of course tongue in cheek (whose favorite actor is Brian Dennehy?[1]), but it also opens a doorway into Kenny’s entire world.

The song is structured around a normal day exploring Kenny’s favorite parts of Chicago. When he forgets to pick up minute rice for his adored wife Jueles (“Back in the damn Buick!”), he takes us in a trip down Western Avenue [2], listening to WCKG 3]. As he fleshes out this image of Chicago, perceived through Kenny’s navy and burnt orange-tinted glasses, Cohn glorifies ordinariness. Kenny’s comfort doesn’t come from any sort of wealth, but actually from his life’s banality (there isn’t even alcohol in his beer). It’s about finding solace in what you have and getting the most enjoyment out of that. A happy medium, or as Kenny says, when he raps some advice on cooking brats: “Your heat shouldn’t be that hot.”

In an odd way, “Dennehy” actually follows common notions of literary realism. In a realist novel, the author creates the illusion of a realistic (but fictional) universe through the accumulation of details that familiarize and introduce us to the world they have created. Cohn’s creation of Kenny uses this method, as we get to know his experience of Chicago through the details that construct it. On “Dennehy,” Kenny raps about everything from minute rice, his wife Jueles, laserdiscs, and weed whacker fuel. But Kenny’s ridiculousness also brings out another crucial aspect of realism: Kenny is the instantly familiar guy who listeners can easily imagine knowing but that nobody actually does. Writers and musicians can create a fictional world in a realistic manner, so their readers or listeners can imagine living within that world, but only on the condition that none of this actually exists. Realism requires a simultaneous and conflicting (but not contradictory) appeal to both faithful representation and distorting artifice. Put

another way, it makes as real a world in as fake a manner as possible. This principle, by which Kenny can seem both familiar and impossible, is what allows Cohn to create the character, but it also drives the creation of ever more Kenny albums.

“Teachaz in the building like supers and tenants”

The first thing that doesn’t cohere about Cohn’s portrait of Kenny in “Dennehy” is that Kenny Dennis can rap as well as, well, David Cohn. Why can this boring nobody from Chicago rap so well? To explain Kenny’s ability to rap, Cohn decides that he was, of course, in a hip-hop group back in the nineties. And so Tha Grimm Teachaz were born, with the 2011 album There’s a Situation on the Homefront. Or if we’re living in Kenny’s world, that album was made in 1993, two years after Tha Grimm Teachaz formed, after Fresh Greg introduced Lamont Toussaint (PMDF—Prince Midnight Dark Force) to Kenny (KDz—Killa Deacon) and producer DJ Koufi. The album was subsequently lost, only to be unearthed by Kenny’s brother in 2011.

Cohn unfolds two stories at the same time, one fictional about a nineties hip-hop group that would create Kenny Dennis, and the other (meta-fictional) unfolding in our reality, as Cohn makes an album that sonically resembles something that could have been an underground hit in 1993. But both stories proceed in the direction of faithful realism, using narratorial, formal, and material methods to convey as realistic a portrayal of Kenny Dennis as possible.

Cohn’s exploration of mundanity, realism, and happiness is also an exploration of rap’s ability to convey these representations. It’s about rap realism, both in the sense that Kenny really sounds like a rapper and that his story’s proceeding through rap has consequences for Kenny’s reality. Cohn shows how genre and medium are not simple means of deploying a story but actually transform that narrative’s content. A meta-fictional album like There’s a Situation on the Homefront becomes both a narrative and a generic requirement. Because Kenny’s life story is told through rap, that same life story is changed by the generic conventions and necessities of rap songs and albums.

Tha Grimm Teachaz’ songs blend intricate and clever rhymes across songs that craft each of the personas these rappers embody. They’re at once fictional and meta-fictional, as both Kenny and Cohn portray Killa Deacon. Tha Grimm Teachaz are at once both Kenny’s fiction and his listeners’. At times, There’s a Situation on the Homefront feels like a representative sample of 90’s rap by musicians ranging from 2pac and Biggie to Naughty by Nature and Mobb Deep. The album includes smooth jams (“Whutchyougonnado,” “I Getz,” and “Grimm Teachin”), hyped-up party tracks (“Got R Own Thing” and “Ay Muthafucka”), comedic stories (“Melissa”), and diss tracks (“Frontin,” “Double M,” “Poobutts,” “Snap Ya Neck,” and “Grimm Savyas”). These various songs, combined with the spoken interludes by Fresh Greg and the album’s final, titular track “There’s a Situation on the Homefront,” give the album a critical edge, distrustful of the systems of power that these rappers are (grimm) teaching you to see beyond. As Fresh Greg explains on his last interlude:

Take something like mini blinds, right? Whether they be, you know,

whatever mini blinds in your house or hotel . . . mini blinds. break that

down: many blinds . . . there’s many blind people; that’s how they want

us to feel . . . I don’t fuck with no mini blinds. If anything, it’s going to be

drapes.

This absurdly paranoid outlook finds firm ground in the album’s closing track. The titular “situation on the homefront” is the war on drugs, as police officers frame innocent, predominantly black, people for drug-related crimes. Early in the track, KDz raps: “They wanna throw you in the clink / just cause you smoke pot / destroying our communities / giving us crack pipes.” Over a beat that resembles war drums (and samples a crowd chanting “vengeance”), Tha Grimm Teachaz direct their community to this harm. Cohn, writing this nineties album in 2011, knows what the Teachaz could only predict: The war on drugs is ongoing, if not in the same manner the song identifies. There’s a Situation on the Homefront, then, involves a sort of retrospective prediction, as Cohn conjures a past moment that he

knows will lead to his present. This same historical imagination occurs on a stylistic level too, as Cohn makes an album that would have been cool in the nineties. This seems antithetical to the way we normally think about coolness as something ahead of the curve or aloof to played out trends. This stylization ties Cohn’s meta-fiction to the layers of irony in Kenny’s life. They both incite the creation of more music in an attempt to keep up with Kenny as his world evolves.

Tha Grimm Teachaz almost had their big break, playing on a Jive Records showcase at the same time when Shaquille O’Neal [4] was at the height of his rap career. Shaq insulted Kenny’s mustache and he could not forgive him (hence the numerous Shaq disses that litter the album). There’s a Situation on the Homefront was not released until its rediscovery in 2011. But there is a rumored other Teachaz album—Da End iz Near—which is still waiting re-discovery (or, you know, for Cohn to record it).

“Talking ‘bout the ‘stache look silly”

After the Teachaz break up and Shaq’s rap career has faded into a distant joke, Kenny’s life goes on, and the reissue of his long-lost rap opus leads him to resume his rap career. Cohn expands Kenny’s life in a series of three albums, Kenny Dennis EP (2012), Kenny Dennis LP (2013), and Kenny Dennis III (2014). These albums show Cohn slowly progressing from the sort of portrait that “Dennehy” painted of this oddball character to an intricate narrative of Kenny’s later life. In the process, Kenny’s life becomes more and more unhinged as he struggles between comfort in his current life and the past glory that he had with the Teachaz. And as Cohn experiments with rap’s affiliation with narrative realism, the ideal of a mundane utopia becomes more complicated than it first appeared.

On Kenny Dennis EP, each song gives insight into Kenny’s personality. The diss track “Shazam” explains Tha Grimm Techaz breakup, as Kenny relives his past feud with Shaquille O’Neal. The beat is characteristic of Serengeti. It’s gritty and takes lots of cues from old school hip-hop. Kenny even recycles a line from Tha Grimm Teachaz’ song “Double M” to air his beef with the former rapper and basketball player, but now it becomes the song’s hook: “Shazam, Shazam, Shaq don’t want none. / Jolly Green Giants get cut.” Toward the end of the song, the beat grinds to a halt, only to start back up in a lighter, more upbeat version, as the drums play on the high hat, rather than the toms and bass that had dominated the song so far. Over this re-worked beat, Kenny goes through the hook one more time. Cohn sonically recreates the way in which Kenny relives his past. The beat may have changed, but he keeps spitting the same rhymes.

The beat that closes “Shazam” creates a sonic introduction to the second half of Kenny Dennis EP. Opposed to the forceful attacks of “Shazam,” the last three songs, “Top That,” “Kenny Dennis,” and “Flat Pop” depict Kenny rambling through accounts of his own life. No longer in your face, we meet

an aging rapper, recovering from his glory days, who wants to tell you about his life. Even when it sounds like he’s bragging, Kenny now takes us away from the house parties that backgrounded Teachaz tracks. In his anthem “Kenny Dennis,” he raps: “I was at a charity dinner / for kids with troubles walking / I had to shush the table / cause Tanya kept talking.” The blown-out sirens that used to make up beats would now be much too loud for Kenny.

Music has more room for this kind of banality than fiction, poetry, and film. You can write a million songs about the same topic (see: heartbreak) that don’t get old as quickly as short stories or novels. This is not because we hold music to a lesser regard but rather because it more readily conjures the texture of a full situation, in a way that the written word often fails. Hip-hop especially achieves this, with its tendency to sample sounds from the “real world” and to use frequent spoken interludes. This is the power that Cohn taps into when he conjures Kenny’s past as Killa Deacon, re-inhabiting the rap career that never took off. Listeners are not only told the story of a washed-up rapper, but they actually hear his practiced flow decline in skill, as his taste changes and he picks it back up twenty years later.

“All you need now is some direction”

Kenny’s comeback comes into focus on the next two Kenny Dennis albums. Both projects prominently feature the character Ders, played by Anders Holm (most widely known from the TV show Workaholics). In these albums, Cohn focuses less on individual songs in favor of sketches staged over beats. Across the two albums, Ders narrates his friendship with Kenny, who speaks in the background. This is not just a story about rappers—it’s a story told in rap that passes the narrator’s role between voices. This polyvocal narrative procedure also frames Kenny’s main conflict, as his eventual inability to resolve his self-identity with reality strains those around him.

This oral history approach to Kenny’s life initially enamors us to the rapper, letting us see him through the eyes of those who care about him. Kenny meets Ders as a young kid in a Sharper Image in 1988. After Kenny can only get store credit for a non-fogging shaving mirror that wasn’t working, he sees that young Ders can’t afford a Christmas present and picks up a shower radio: “Now this is a good piece of equipment. Hey, kid you want that?” Kenny’s monologue continues in the background, as Ders explains this meeting:

I don’t know what it was. He just knew that I couldn’t afford a present, or

whatever. He just got it for me because that’s Kenny. He’s just that guy.

And then, I know it might sound weird, but he gave me his phone number.

And I can even remember the phone number still. It was (708) 242-

7232.

While both characters are speaking more or less naturally (with Kenny in his thick accent), the beat lines up Kenny’s and Ders’s monologues so that they both finish reading Kenny’s number at the same time, even though they began it at different times. This sort of vocal unison and dissonance

sounds out the drama across Kenny Dennis LP. Cohn can sonically illustrate Kenny’s connections to and distances from those around him. This same narrative technique also lets Cohn reveal some darkness in Kenny’s life, while letting the character Ders remain oblivious. The late album jam “West of Western” frantically jumbles a series of impressionistic scenes, as Kenny finds himself in Reno. It’s the first mention of Kenny’s Benzedrine habit, which he apparently curbs by drinking the non-alcoholic O’Doul’s beer: “Laying off the Bennies / . . . / Started drinking O’Doul’s/ Stopped getting smashed in, stopped getting smashed in” [5]. The narrative of a recovering addict explains some of Kenny’s ridiculous tendencies, as Cohn also shows his life beginning to unravel. In the song/sketch “50th Birthday,” Ders flies Kenny out to LA to say thank you. Kenny’s irritability strains the friends’ relationship. Kenny eventually dips out before they even sit down to his birthday dinner, taking a Greyhound back to Chicago, and Ders is left forlorn and alone, both in the situation and on the song: “If

Kenny’s gonna listen to this—is he going to hear this?—well then, tell him I say ‘what’s up’ and, you know, I miss him.” After Ders’s monologue ends, Kenny comes back on the track, also alone. He rambles on, telling Ders to give him a call and advising him not to “forget about his roots.”

Everything in Cohn’s portrayal of Kenny constructs a rich portrayal of his fictional world. The constant interplays between characters like Kenny and Ders build sympathy for the two men. With Kenny’s weird habits, thick accent, and strange personality, all of this can easily become a joke, but Cohn’s project actively resists comedy. Cohn shows Kenny in often ridiculous situations, but there is no punchline. He doesn’t want us to laugh at Kenny. He wants to build a compassionate picture of him, so that we can imagine ourselves in his life. This almost sentimental creation of two characters just trying to build their own mundane utopia falls apart as the narrative proceeds into meta-fiction.

“It’s not hard being the Dz, but being the Dz is great”

Kenny Dennis III begins by healing the wound that closed Kenny Dennis LP. Ders calls Kenny, they decide to start rapping together, and Ders moves back to Chicago. In the meantime, Kenny has it all planned out; he has beats ready and picked out a name: Perfecto. The name conjures a different image than ‘Tha Grimm Teachaz,’ and Kenny’s musical style changes completely. What was once gritty hip-hop, Kenny has now turned to hyped-up pop jams, reminiscent of C&C Music Factory (to use Ders’s comparison). The song “Perfecto” replicates this change, as it abruptly switches from a beat that replicates a record skipping to upbeat synths. Ders’s immediate reaction puts Kenny off, foreshadowing their eventual split: “That’s funny.” Kenny’s response echoes throughout the album: “What do you mean ‘funny’? These beats cost me a lot of money.” As opposed to the meta-fictional Tha Grimm Teachaz, Cohn dives into the conflict that arises from these two characters creating their own meta-fiction together. In this way, meta-fiction becomes the grounds in which fictional conflicts are worked

out. It becomes the point where banal utopias break up because two fictional characters refuse to agree on what constitutes an acceptable fiction within their life.

This conflict partially arises through Cohn’s own experiments with rap. There is no singular narrator of Kenny’s life story. Details get lost, and characters contradict each other. But an overarching guide comes through the beats, over which these lives narrate themselves. If the tempo increases, characters necessarily start talking more quickly, and tensions rise. When a beat abruptly drops out, conversation stops, and we have to pick it back up in a different song with a different scene. There is no narrator, just multiple conflicting voices, but Cohn and the album’s producer Odd Nosdam play a narratorial role in their creation of the music that subtly directs this story.

But at first it seems like Kenny is onto something. Perfecto starts touring the best malls and rec centers in the Midwest, performing to packed houses and wearing tons of Aeropostale. Ders catches Kenny’s excitement in the process:

We went up to Rockford and like shut the place down; it was crazy. We’re

doing Battle of the Bands, and it’s just cool, man. We even did Lincolnwood

Town Center, which was like a nice homecoming for me because

that was the closest mall to me growing up.

Perfecto’s performances reach out to an uncool and forgotten suburban demographic. It’s a caricature that imagines what would happen if the suburbs somehow produced their own genre of music.

Between the songs that advance this story, the album is populated with a series of strung out ramblings by Kenny. These songs largely resurface moments from Kenny’s past that he’s unable to get over, such as the revelation that Kenny at one point had the chance for a rap battle with Shaq. Contrasted to the sketches that largely narrate Perfecto’s story, Cohn’s bursts of rapping on these other songs express the release of Kenny’s confessions, as though he just needs to get something out. The rhymes feel incomplete and less clever than usual: “When I bumped into Shaq I was too scared to battle / shaved off the ‘stache I was feeling sort of rattled.” The fact that this rhyme feels at once obvious, but it’s only a half rhyme, shows Cohn using Kenny’s artistic shortcoming to heighten this moment’s realism, as Kenny slips back into his Benzedrine habit. The group eventually breaks up. Kenny is overbearing, as his ego grows from reliving his Teachaz days. Ders gets a call to audition for the role of a young Mr. Drummond in a Diff’rent Strokes prequel right before their chance to a play a talent show at Mall of

America. In the ensuing argument, Ders frames Kenny’s problem as an inability to get over the past: “That era is over, therefore this is a joke.”

Moments like these separate the respective interests of Cohn and Kenny in recreating these past musical moments. Cohn’s meticulous recreation of something like There’s a Situation on the Homefront represents an interest in revising history from the present’s vantage point, as one way of recuperating something that was lost. But Kenny’s inability to get over something like Perfecto instead shows a sort of inability to cope with the present moment that is passing him by. When Cohn goes makes a meta-fictional Perfecto EP, You Can’t Run from the Rhythm, it features many of the same

experiments that he worked out on There’s a Situation on the Homefront, but puts them to a different end.

You Can’t Run from the Rhythm shows Cohn still experimenting with the narratological interplay between producer and rapper that he did on Kenny Dennis III, but now it occurs within Kenny’s meta-fiction. We see a character telling us his own life story at the same time that he tries to fashion a new career for himself. Instead of imagining a band that would have been cool in the nineties, Cohn and Holm portray the band that will never have the same sort of prestige that a long lost hip-hop band has, ironically depicting Kenny lagging behind the times. In the same way that Cohn textures “Dennehy” with intricate and thorough references to Chicago, You Can’t Run from the Rhythm captures an early 2000s moment. Opposed to the analog warmth that characterizes Serengeti’s music, Perfecto is backed

by frantic, digitally manipulated beats and vocal samples that stretch and speed up everything. If Tha Grimm Teachaz were an attempt to insert Kenny Dennis into a different past, Perfecto is an ecstatic way to try to catch up to our present moment. This is what the album’s title expresses. The band’s “rhythm” conjures a frantic moment from which none of us can run.

“All of Kenny’s rhymes should be studied in humanities”

Maybe the most inexplicable part of Cohn’s creation of Kenny Dennis is that everything gets explained. Not only does the fact that Cohn raps his depiction of Kenny’s story spawn a nineties hip-hop group Tha Grimm Teachaz, which in turn occasions Kenny’s mid-life crisis mall-core band Perfecto. This meta-fictional proliferation of bands that break up and then resurface provides the occasion for this story’s end, in the last Kenny album, with the revelation that Kenny’s oft-lauded wife Jueles (portrayed

by the singer Jade) has had a career this whole time. She releases Butterflies (2017). The music is great, but Kenny keeps getting in the way.

Butterflies blurs the line between fictionality and meta-fictionality that Cohn has explored throughout the Kenny albums. Kenny’s story is further narrated on the album (such as on the track “Ders,” when we learn that the two are no longer friends, despite Kenny’s attempts to reconnect), but he also becomes a featured collaborator, on such songs as “Places Places.” Butterflies is structured around a series of songs called “Wheels,” each of which features a car’s ignition and idling that slightly distracts from a catchy track by “Stace” (Jueles’s sister, played by the singer Nedelle Torissi) on the album:

Quickly realized that you

Really weren’t the one for me

Time for you to leave

I’m the S-T-A-C-E

As the song’s recurrence reveals more excerpts from it, Kenny’s rapping over Stace’s voice becomes more prominent in the way that his breakdown increasingly encroaches on Jueles’s and Stace’s lives. In its last iteration, “Wheels” loops Stace’s hook “just leave me alone,” as Kenny’s rapping speeds up, as though Stace is telling Kenny to leave her alone. Kenny’s encroachment on Jueles’s life also gets worked out on the song “Odouls” [sic], on which she laments “I gave you the best but all you expect was O’Doul’s,” a beer that she characterizes as “what beer drinkers drink when they’re not drinking beer.” It’s as though, even with Kenny’s crutch of O’Doul’s to curb his addiction, he will always be a “beer drinker,” with all the attendant habits and burdens.

The album follows multiple friends leaving Kenny, as he calls people ranging from Ders to Shaq, none of whom pick up the phone. The last of these calls, depicted on “The House,” features a phone ringing, while it rains, and nobody picks up. The call is presumably to Jueles, who has kicked Kenny out, but it could potentially be any person in Kenny’s life. On the next track, he repeatedly asks Jueles to “cut [him] some slack.” This abandonment culminates in a haunting musical and mental breakdown at the end of the song “Duet.” Kenny repeated shouts of “No” and “Say what?” become increasingly garbled through echoes as the track fades out. Cohn’s abstract portrayal of the scene leaves it unclear what exactly happens to Kenny, but we get the sense that his story is over by the album’s sprawling penultimate track. “Grief Stages” opens with an oscillating beat that pans from right to left as though it’s closing in on the listener. The largely instrumental track works through a series of phases (the titular “grief stages”), until it closes with Jueles singing, “Don’t look back / with regret / life moves on.” In the album’s last song, there is no mention of Kenny. It’s just Stace singing to her sister Jueles: “In a dark world, you made me feel so safe/ taught me how to embrace heartbreak of life.” To escape Kenny’s influence on their life, Jueles and Stace have been making their own fictions all along.

What is a meta-fiction in which the fictional creator’s story has ended? At that point, it might just be someone else’s story. Ultimately, Kenny could not tell his story by himself. It was always a result of multiple stories being told at once. As Jueles sings, “life moves on,” and fiction works in the same

way. Despite the fact that it feels like these fictional creators have agency, it was never really Kenny’s story, and he had no control. Cohn instead created a rich, fictional universe, in which Kenny’s desire for mundanity is both celebrated and challenged. Even in Kenny’s ultimate failure, though, Cohn finds some glimmer of hope in the fact that he at least tried.

“Lace up your shoes: Tonight, you’re turning forty-two”

It’s too easy to write Kenny Dennis off as just a joke. While there are aspects of Kenny that seem wholly ridiculous (I’m still wrapping my head around the fact that his favorite actor is Brian Dennehy), Cohn makes his story expansive and dark, but he settles on an exuberance that overcomes Kenny’s struggle. This joy does not come from glory, fame, or wealth but rather from the sort of pleasure in the everyday that introduced Kenny to the world.

While Butterflies was Cohn’s last Kenny Dennis album, he will continue to tell his story in a forthcoming graphic novel. The project was teased with a zine version of Kenny Vs. The Dark Web: A Prologue, with which Cohn accompanied the song “Get it While the Getting is Good.” This most recent (and probably last) Kenny Dennis song is pure celebration. Cohn’s bouncy and catchy beat, launches Kenny into a joyous rap: “Let’s go, let’s go / Get it while the getting’s good / Riding in a limousine / About to celebrate like tonight you’re turning seventeen.” Cohn jumbles ages and time periods. At one point, Kenny celebrates like he’s turning seventeen, but later, he’s celebrating his forty-second birthday (even though Kenny had already celebrated his fiftieth birthday on Kenny Dennis LP). The inability to pinpoint this song’s place in Kenny’s fictional life is part of the point. Rather than worry about where Kenny’s narrative goes, Cohn instead settles on his own engagement with the character that avoids narrative cohesion. He finds a final exuberant pleasure on which to settle, regardless of where Kenny left himself.

Serengeti’s creation of Kenny Dennis is a way to question how we find pleasure in life.

Approaching a grill of brats, a Brian Dennehy flick, a suburban mall, or your forty-second

birthday with ecstatic enthusiasm is Kenny’s celebration of life, as a sort of redemption

from the pain, abandonment, and harm that we might choose instead. You just have to,

like Kenny, “get it while the getting is good.”

[1] To save you from Googling, Brian Dennehy is an American actor, most well-known as the police officer

villain in First Blood, the film that launched the Rambo franchise.

[2] The longest continuous street in Chicago.

[3] A popular sports radio station, serving the Chicago area.

[4] As much as Cohn is making up history through Tha Grimm Teachaz, Shaq did actually have a rap career. Some things are stranger than fiction.

[5] Cohn mentions Kenny’s penchant for O’Doul’s in an interview with TinyMixTapes, after Kenny Dennis III, but the connection between bennies and O’Doul’s comes up as early as Kenny Dennis LP.

Adam Fales is a PhD student at the University of Chicago. His work has appeared in the American Antiquarian Society’s Past is Present, the Journal of the History of Ideas’s blog, Full Stop, and the Los Angeles Review of Books. You can find him on Twitter @damfales.

This post may contain affiliate links.