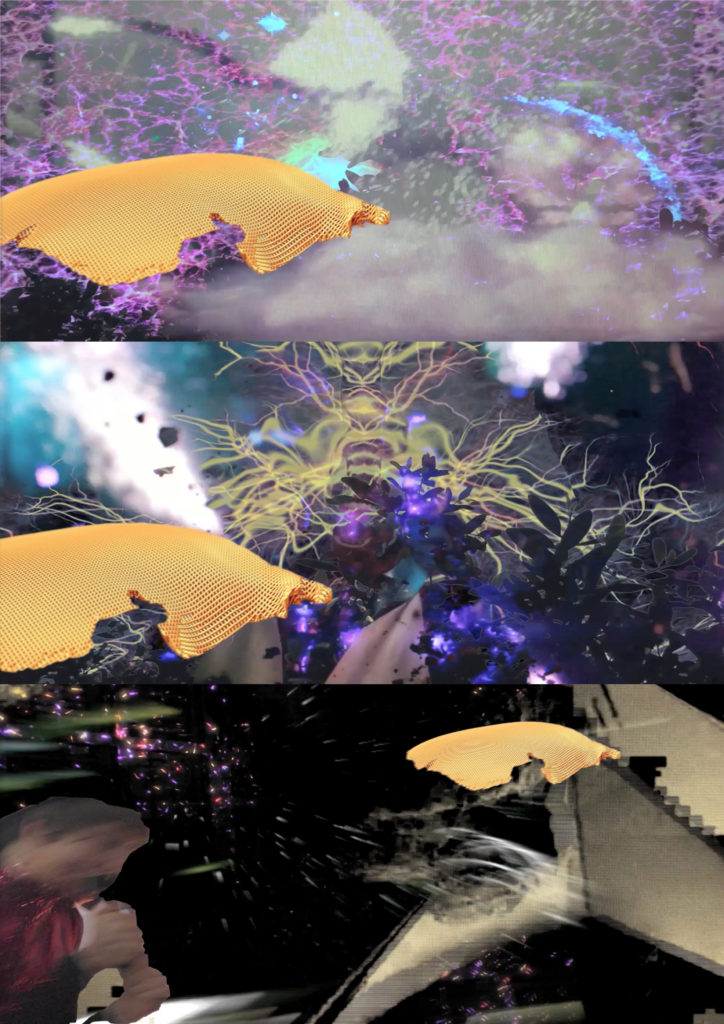

“Artificial Gold: Unruly City,” 2017

Video stills and digital collage, by MER Maggie Roberts

This essay first appeared in the Full Stop Quarterly, Issue #6. To help us continue to pay our writers, please consider subscribing.

Every few months I scroll through my Twitter feed and decide I don’t know how to be a queer poet on the internet. I have no qualms about over-sharing the minutiae of my floundering sex life or of looping Vince Kidd’s “Like a Virgin” performance on The Voice UK, but I doubt the process’s utility. In any given month I’ll tweet hundreds of tweets but feel lucky to add even a single poem to my drafts folder. While I used to think of Twitter as a notebook from which I’d pull lines into poems, time has shown a greater likelihood I’ll tweet without ever recycling that material. I’ve unwittingly allowed my poems to be replaced by what I’d thought was their promotion.

Through my graduate school years Alex Dimitrov had me convinced this wasn’t a problem. Here’s a poet, I would think, just a few years older than me, rising into fame, and he’s still publicly passing off Grindr screenshots for poems in e-chapbooks and hosting private readings in the beds of Brooklyn’s twinks. And of course it worked . . . I’ll confess here that my adoration for his debut, Begging for It, was tinged with the desire only possible when one first enters an MFA program; though we’d never met, I couldn’t turn a page without remembering the black, skin-tight jeans he wore to escort Anne Carson to the main stage at AWP. I believe that was the year I noticed printouts of Rimbaud’s face plastered around the bookfair. While I have no evidence to say Dimitrov was responsible for these faces, they were the same used by David Wojnarowicz on the cover of Begging for It—enough of a connection for me to wonder about adapting guerilla marketing for poetry. I was dizzy wondering what a poem could be and how it could be promoted when I should’ve been concerned, as it seems Dimitrov has been lately, with how a poem could last.

In his new book, Together and by Ourselves, Dimitrov seems almost embarrassed by the overt confessionalism of his first and its promotion. Gone are the days of his staring down the reader while wearing his father’s briefs as a hat (“The Underwear”). He writes in “All Apologies”:

I think I made a mistake in wanting to be known;

but I came to New York and I stayed.

So the rain now feels like a language for warmth

when it’s just like the leaves are:

they fall whether or not you take note.

Here the city is given credit not only for Dimitrov’s poetry career, but for his poems themselves—at least his interest in and capacity to make metaphors. I’ll forego discussing the oxymoronic nature of a “known” or “famous” poet, except to note the rush I’ve felt engaging in trysts with writers, wondering if I’d make an impression on a book that would last; the cultural capital might be slight, but the romantic is not. This book couldn’t exist had Dimitrov avoided the city or the men who inhabit it. Like a life or the rain, a city is what you make of it. While New York indeed makes it possible to be known, it could have also allowed the opportunity to hide in anonymity among the crush of humanity. Later in the poem Dimitrov writes, “We could let a coincidence end us completely,” and it strikes me how often coincidences are more likely to lead to poems.

As often as Dimitrov is making moves between New York City and Los Angeles, Lindsay Lohan and Elvis Presley, he seems to retreat into the privacy of his poetry. Everywhere he is filled with longing, a quiet desire for impossibilities. He writes in “Chance Visitors”:

It’s human to want the sky with you everywhere.

Inside your apartment. Inside the inside life.

To imagine the sky inside your inner life is to imagine its light everywhere. How quiet it would be, how precious. And I wonder if this is why so many queer people turn to poetry for solace or reflection; here finally is a space you can be completely open without fear of judgment or harassment. When poets aren’t famous we can say anything. Our work is a utopia within the metropolis.

In my first draft of this essay I wasted a considerable amount of time engaging in a classic Dickinsonian/Whitmanian comparison between Dimitrov and Tommy Pico before realizing Dimitrov’s quiet lines weren’t stopping him from engaging in an expansionist view of the country and its emotions, and Pico’s sprawling, book-length ruminations weren’t hampering formal developments on the level of the individual line. Indeed they’ve taught me more about Dickinson and Whitman than the reverse could hope to: Dickinson may have stranded herself in her room and her writing, but her imagination carried her poems in the same way Whitman’s did—he may have seen more of young America, but his visions of it were certainly compromised by his imaginings and his longings both for distance shores and the young men who frolicked there.

In this way Dimitrov seems to me closer to Whitman; while his poems locate and concern themselves in and with cities on both coasts, their imaginative space is concerned with what the poet couldn’t possibly know about his companion’s experiences and ends up returning Dimitrov inward. In “Out of Some Other Paradise,” for example, people walk out of “churches and bars, / cafes and apartments, cities, towns, photographs . . .” in a litany of perhaps hundreds of strangers, and the poem’s imagination winds its way through their expected loneliness before returning to the speaker at the end of the poem:

What can be said about what we do to each other.

What street, I don’t remember,

on the way to someone’s going-away,

I saw you, as if in the middle of a sentence,

snow: your new evening clothes.

Here we’re allowed to see the “you” as the ars poetica, simultaneously abruptly returning the poem to the speaker and his imagination. If the snow is his new clothes, we can assume the speaker remembers his unclothed body well enough and without suitable distance to avoid the necessity of the preceding poem, a distraction from a lost “paradise,” as the title implies.

Where Dimitrov bemoans the love that was lost, Pico bemoans the inadequacies of the love that could be. Nature Poem is primarily concerned with how to write a nature poem while not writing a nature poem “bc it’s fodder for the noble savage / narrative.” Pico, a self-described “weirdo NDN faggot” born on a reservation in California, works to overcome this conundrum by reconciling into a language of his own the languages of English, the internet, nature, and the white men trying to sleep with him—none of which quite fits the bill. He writes:

Tracing shapes in the stars is the closest I get to calling a language mine:

The Ripening Mango. Three Snaps in a Z Formation. Amy Winehouse.

Naming is basic and audacious, a claim

The problem here, of course, is the reluctance to actually stake that claim, to demand dominion of a thing that couldn’t, shouldn’t, or won’t be owned. This is perhaps Pico’s greatest difference from Whitman; while the latter took delight in naming and using and moving forward, Pico has the wisdom to take things more slowly, to fully engage with the universe around him. While this caution at times gets Pico what he wants, it does so while simultaneously costing him a bit of the progress he’s made toward establishing his own voice. By what Pico “wants,” here I’m referring to the young men splashed throughout this book. James in particular is trouble:

When James hugs me hello

he stoops

(bc he is very tall)

nuzzles his forehead into the hook

of my neck

takes a big, long sniff

growls soft and low.

James is a stone

cold

dummy. But when he does that?

If this was an 80s hard band music video

I wd totally groupie

toss my frillies onto the stage . . .

In a later section, James’s “dummy” nature commandeers a dialogue between him and the speaker, in which Pico decides to “say nothing cos I’m tryin to get lucky” rather than risk a confrontational dialogue over how “facts” are used in America to either simply be a fact or to “subjugate, intimidate, enslave, and kill . . .” We see Pico capitulating to a (presumably) white man for the possibility of a sexual encounter. James, while magnetic and tall, is clearly no good for Pico, yet Pico finds himself unable to dismiss him. While the men in Dimitrov’s poems seem to be there hoping to be included, James seems incapable of such elevated desires. This too is nature, how we lose count of the men we’ve stayed with simply because they were there.

What is most interesting to me about Nature Poem is how it collapses the distinctions between types of nature. The interpersonal nature, the natural nature, the artificial nature. If humans are natural, it is not too big a stretch to imagine what humans create as part of the natural as well. For Pico this seems slightly overwhelming, because what else is there actually to write about, but muddling through these forms has given rise to a poem written in a language so beautiful the distinctions seem irrelevant. Indeed in places the poem feels more like a text message or a chain of tweets, abbreviations and all, but this is exactly where we are. While Dimitrov has taken to isolating his poetry from his online persona, Pico blends the two seamlessly, especially when employing phrases like “let’s say,” a popular online construction which allows the speaker to divulge a story or a piece of gossip without directly taking credit for the information.

In his tendency to report sights and experiences in lieu of naming or claiming their subjugates, I wonder if Pico is also harboring a desire to remain anonymous. Everything is a secret if everything is presented for consumption. This seems to me a crucial act for young queer poets; after years of suppressing every desirous thought, how wonderful it feels to make everything accessible, even if under a pseudonymous social media account or the guise of the so-called “speaker” of one’s poems.

More than anything this seems to be the link between Pico, Dimitrov, and those I follow on social media: In our constant fight to feel accounted for inside the crowd, we shout, we overshare, we reword until others think it sounds beautiful enough to publish—whether we are distilling that experience to its most basic, relatable pieces or pushing the boundaries of how that experience can be shared. The upside of this is we get to see immediately how not alone we are. Surely hundreds of others have desperately wanted to ghost from a party or get a nose ring at thirty.

I’ve taken to responding “reading poetry” when boys on Grindr ask what I’m doing. Often they respond with confusion or with negative memories of high school Shakespeare, but when they ask “why” I respond honestly: “to feel heard.”

Doug Paul Case is a photographer and writer based in Bloomington, where he recently earned his MFA from Indiana University. His work has appeared in Salt Hill, Hobart, Salon, and Voicemail Poems.

This post may contain affiliate links.