Here, a vision: a poem as the fly caught in the spider’s web. A poem as the spider, the web itself, the silk of it, sticky. A poem as the dark corner of the window where the web hangs. A poem as the window, the world outside, the whole vast spanning mess it is and was and will be. You read Keegan Lester’s work and this is what a poem is, forever. Ambition and failure. Regret and the winding-back. Some hope, so much loss and, still, joy.

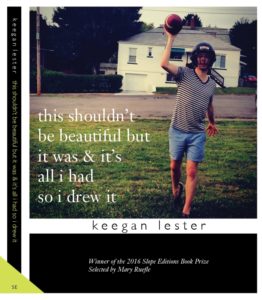

In his collection this shouldn’t be beautiful but it was, & it’s all i had so i drew it, he writes, “are we all not a little wounded?” It’s an honest line and, more importantly, an honest question—pushing toward the varied ways in which we each hurt, and, perhaps by silence, pushing toward the multitudes of ways in which we try to overcome such hurt. So much of Keegan’s collection is like this. It feels first, and then enacts, moves, and turns. But it is all grounded foremost in feeling. That risky word—sentimentality. I hesitate to use such a word because of its connotation; but I use it because, yes, Keegan’s work is full of sentiment, the heavy clinging weight of it. But it is honest, and true, and good. And that matters. Matters so much.

A great deal of art stems from curiosity, from loss and failure. In Keegan’s work—and this conversation as well—I feel some sense that the getting-there or the going-back or the falling-down is more important than arrival. There’s so much we don’t know. Keegan Lester, I think, is trying to tell us that. I hope you listen and find in such listening a sense of comfort.

Devin Kelly: So much of your collection drives itself forward based on what I would call simple and honest heart. There’s just so much love here. I think of these lines: “put these hills on / my shoulders. i know it takes more to be born / again, than the hills i’ve placed / myself.” I read those lines on the subway for the first time and felt like reaching out to comfort someone I’ve never met. What pushes you toward and then through a poem? How important to you is the necessity of heart, of trying to convey feeling?

Heart comes from the conviction and sincerity of really wanting to understand the world better. It comes from a place where as I get older and more self-aware, I just don’t give a shit about the cool kids in poetry or the scene, or what I’ll be remembered as, or if I’ll be remembered. My approach to writing stems from a want to entertain others, to move others first. To create a gift for someone else. It’s a reflection of the kindness people have shown me.

Heart was always the most natural place for my poems to begin, but in the last three or four years learning to be comfortable with putting my own intelligence aside, to allow for the poems to have their own separate intelligence, was a huge development in my art. This is to say that my poetry got much better when I stopped using poetry as a means for intellectual personal gratification and more as a vehicle for entertaining others.

When I started writing for others more so than to impress people in a workshop or to prove I could write a certain kind of poetry, the writing got better. When I stopped writing poems for poets to read, the poems got better. Why is it as poets we think the only way to write is in such a way that accessibility can only exist just beyond the reach of non-poets? It is my ambition and goal to write for a larger audience than that. To write for people who are non-poets. This is not to put down higher lyric work. I come from that lineage. I just know what works for me, and what my goals are. I also love being on a stage and think I’m more effective when put on a stage.

The creativity which we utilize to move information is just as important as the information itself we are trying to put into the world.

Realizing writing elliptical poetry, for me, would make it so that I would reach a smaller audience, in an already tiny population of people reading poetry, just seemed misguided and a bad business model for my work. Over the years I’ve had teachers tell me about how they hate readings because the work goes over the heads of the audience. That is not something I discredit them for, but I know for a fact that for my work to be successful it has to work on multiple levels and one level must do the work of inviting the audience in. I think I do that with humor, performance, and sincerity.

I’m self-aware enough to know I’m only really talented at this one thing. If I’m going to succeed in this life, I have to push the boundaries for which I use in this genre to attract people. I have to be more creative in my approach. I am not brilliant nor talented enough to have a fallback career.

There is a sense, too, of dedication with this collection. I’m thinking in particular of the poem that begins “to my mother painting humming birds” and the repetition of this need to give this book to someone, something. I feel so strongly a defense of longing, of nostalgia, of suspension—being in many places at once. Want. And poetry’s ability to speak to such things. What are your thoughts on this? And how do you see the poet’s role—your own role—in this new world? What does the poet have to give?

A friend of mine once told me that if you make something for the right reasons, it’s to learn something about yourself. And so these poems spanning 10 years of my life (and being the second book I wrote/first to be published) do time travel, and they do span many places, because I have. But I’d argue in ways where I might have been quicker to defend place and people in earlier work, I’m probably more hesitant here. It’s hard to tell if that’s true. Different people have read different things into this, and I like it that way. I don’t want to be anyone’s manifesto. I’d rather be the thing someone has on their nightstand that they turn to when they need it.

I think the poet’s role is specific to their motivations, but I don’t know if you always get to choose that. I think one becomes something to an audience and then you are that thing. I just want to help people get closer to the feelings they want to feel. I merely want to entertain. If I could impart something it would be that anything we love or cherish or are in awe of comes at the cost of something or someone else, and to be mindful of that. Often by the time we figure it out, we are too late. I hope this book serves as a gift for someone else, to help in their journey forward.

You are a poet of multiple places—right now, West Virginia and New York City. How does this affect your work? Obviously, I’m thinking of that poem directed toward those appropriating Appalachia, and how Scott McClanahan—such a darkly funny, biting writer and defender of the everyday—has blurbed your work.

I was having dinner one night with my mother and she said she liked a new poem I’d just published. And she liked in the bio that I said I was born in California. She said that it sometimes hurts her that I so strongly identify with West Virginia, because she thinks people might think I’m bitter about my upbringing or that she wasn’t a good mom. So for the record, “Mom, you’re a wonderful mom.” And there was nothing terrible about my upbringing.

I mean, I was bullied pretty extremely when I was young, and we did not exactly have the language that we do now to talk about it, but there was never love lacking in my home. But for whatever reason, when I was in West Virginia with my other family during winter and summer breaks, I felt more free, more like me. And it’s the place where I really bloomed into the human I am now, and the place I’ve felt most creative and productive.

My mom is totally understanding of it now, and she understands how much it means to me to be a person documenting that place and loving that place, but I think what happens as a writer or an artist when we take up one facet of our identity it will ultimately let others down who want you to be the version of you that you are to them.

The summer I moved away from West Virginia, (for the second time) a few years back, to New York City to make a go of it as a writer, I discovered Scott McClanahan’s work and read all of it. Feeling particularly homesick, his work made me feel like I was with friends. I love it. I cherish his work because he writes with the same kind of heart and the same kind of folklore scope that I aspire my writing to have.

People often think it’s cool to write gritty or about violence, and without the heart part, the violence and grit part tends to come across as senseless. I think Scott has found a balance in his work that is genius. I think it does the work to show the humanity in everyday people, rather than merely using figures to tell a story. In his work I find myself swirling in the cadences and the language, and his phrasing reminds me of my grandma and there is this almost iambic quality to the way they talk. They both use like 20 words for a one-word phrase. Like; “It’s about to pour the rain.” When I read his work, wherever I am, I feel close to home.

Scott and I met the following summer on a tour I was reading on with the Travelin’ Appalachians Revue, which is a weeklong tour with West Virginian writers, musicians and artists, where we go celebrate artists around the state. I got to read with him and his kickass wife Juliet (whose book Black Cloud crushes me in all the ways) at one of the stops.

I was pretty nervous. I said his name wrong in front of a bunch of people. And it was probably not my best reading, but he was really sweet to me. And it was a transformative experience. I saw everything in him that I fell in love with in the story telling of my grandfather on his porch as a kid. I think Scott passed out fudge in the middle of his reading. It was like a preacher preaching, he was so inside of his work. He was speaking from this other place. His performance just takes you to another place. It was incredible.

Scott helped me realize it was ok to write about how much I love my family and how much I love my friends and how much I love people and West Virginia. I didn’t have to write the narrative where people escape or triumph, but could just write about the love I’ve experienced and the love those people share with each other. He, and his work, allowed me permission for that, and I will forever be grateful for it.

You write, in one poem, “i realize, now, we are / supposed to have learned what we have not.” I know this speaks simultaneously to love, relationships, country, politics, history, etc. I can’t get over these lines, and their place in that poem in particular. How do those lines speak to you?

Those lines are pretty heavy for me. I feel like so many of these poems have these little hidden stories between the lines. And the one thing I am sure of at the end of this project is that I am learning. I am slowly but surely moving forward toward a better place. And I know that I’m learning because I go out of my way now to tell the people I love, every day, that I love them. I don’t assume those kinds of things anymore.

This interview first appeared in the Full Stop Quarterly, Issue #4.

Devin Kelly earned his MFA from Sarah Lawrence College and co-hosts the Dead Rabbits Reading Series in New York City. He is the author of the collaborative chapbook with Melissa Smyth, This Cup of Absence (Anchor & Plume) and the books, Blood on Blood (Unknown Press), and In This Quiet Church of Night, I Say Amen (forthcoming 2017, ELJ Publications). He has been nominated for both the Pushcart and Best of the Net Prizes. He works as a college advisor in Queens, teaches at the City College of New York, and lives in Harlem.

This post may contain affiliate links.