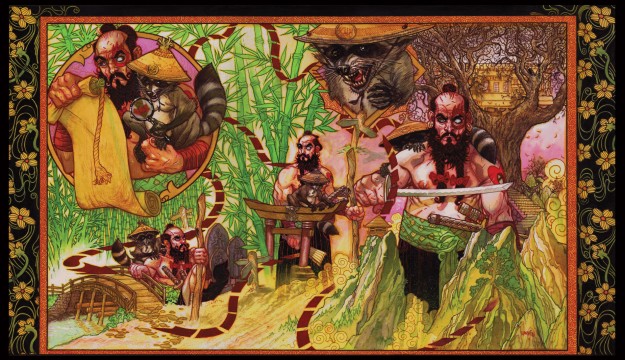

From Roundeye by Tony Harris

With 60-plus projects that have raised over $1 million, and hundreds topping $100,000, Kickstarter has passed out of its “is it just a fad?” phase. But not every creative project or person — even the high quality or well established — is Kickstarter material. Setting aside crisis-driven campaigns and speculative technology as outliers, Kickstarter seems best suited to pushing projects over the finish line, not nudging them out of the starting blocks.

But where does that leave artists and writers without press-ready projects, creators for whom extra support may be the difference between producing new work and being forced into jobs that curtail creative output? It seemed, for a time, that Kickstarter might allow creators to seek support while making work, not just publishing it, but some high-profile failures proved that untrue — in comics, at least.

In 2010, Tony Harris (artist on DC’s Ex Machina and Starman series) sought $60,000 for a graphic novel. His financial target was roughly what he would charge a publisher for penciling, inking, and coloring a 96-page book. The campaign had only raised about $6,000 when he cancelled it. Fans balked at their money functioning as a paycheck rather than producing a product. (A second campaign, seeking $10,000, ultimately brought in over $11,000).

Bill Willingham, creator of Vertigo’s Fables (published monthly since 2002 and parent to multiple subsidiary titles) and Frank Cho, a renowned artist on Marvel properties like The Avengers, failed in their 2013 Kickstarter. The pair sought $30,000 for an illustrated novel. Only $23,000 was pledged. Again, backers objected to their money heading into Willingham and Cho’s bank accounts — and that the initial funding rewards didn’t include the finished work, making the message appear to be “pay us to make this book, and then pay us again to buy it.”

With creators of this stature, success seemed assured from the outset. While both campaigns were hobbled by strategic problems, their failures showed that comic fans on Kickstarter hesitate to fund anything but products that are complete or close to it — which leaves artists and writers in a difficult, almost untenable position. In the best case, artists have advances from publishers, but even those aren’t always enough to free them to focus on art.

This dilemma has spurred a new kind of crowd-funding: direct patronage. Patreon, perhaps the most established player in this space (Beacon, which has a somewhat similar model, recently invited me to join), lets fans support creators making art by giving, often a few dollars, every month. There aren’t always products sent to backers and no one’s buying anything. Fans are helping artists make work they like.

This model hasn’t taken hold in comics (or anywhere else, as far as I can tell) the way Kickstarter has, but it offers a few interesting cases. One is Meredith Gran, writer/artist of Octopus Pie, a light comedy about two women in New York. Gran’s fans have pledged over $1,500/month — not $1 million, but that’s $18,000/year in income above what she would otherwise earn. For some indie artists, that’s a year’s income. With that support, Gran can pay bills and buy health insurance, hire an assistant to tackle administrative tasks, and complete at least 10 pages of her comic each month, according to the site.

A less lucrative campaign is underway for Dave Sim, the writer/primary artist of Cerebus, a wide-ranging comic that he produced every month for 25 years. Sim, an excellent cartoonist and possibly paranoid misogynist, has garnered just under $450/month for his comic about the 1956 car-crash death of artist Alex Raymond. Whether the relatively light response could stem from the limited audience for the comic or Sim’s questionable views is hard to parse (but take me as an example: I think Cerebus is an accomplished, sometimes reprehensible work, but I bought my copies used. I couldn’t stand to give Sim my money). Another campaign, however, suggests that the lack of a clear connection between the donation and outcome could be the culprit in the tepid response.

The most interesting comics-related effort on Patreon belongs to Zach Weinersmith, creator of the geek-centric webcomic Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal. Fans have pledged around $8,000/month. By doing so, his supporters have unlocked rewards including early access to comics, ebooks, monthly Q&As, and livestreams of Weinersmith making comics. Weinersmith has the built-in advantage of a large audience (close to 100,000 people per day, by some measures), but it seems no accident that his campaign, offering a wealth and diversity of rewards, is a smash success. His supporters get something more than just a nebulous, possibly fleeting, sense of beneficence.

The time for bemoaning the vanished roles once served by publishers is clearly past. Business has changed; It’s not changing back. Would we even want it to? How many comics artists would trade a publisher’s support for $1,500/month of additional income. How many successful novelists would trade their royalties for $8,000/month?

It may not be easy for prose writers to succeed to replicate the rewards and bonuses Zach Weinersmith can offer. It’s difficult to ask supporters to wait two-plus years for a novel that embodies the results of their giving. Perhaps a return to serialization and its steady supply of new content could elicit support? If that’s the case, just as with Kickstarter, Patreon and its ilk may not solve the problem of artists and writers making a living wage. But, in comics at least, it may offer another means of wringing some vital support from an increasingly austere marketplace.

This post may contain affiliate links.