Gertrude Stein, the story goes, said to Hemingway, “That is what you are… That’s what you all are… You are a lost generation.” It proved apt as an epigraph to The Sun Also Rises, published when Hemingway was 27, but is also a phrase the media has adopted since Occupy Wall Street took Zuccotti Park in September of 2011. It’s hard, though, to believe any generation — alienated from their parents’ world by technological and cultural shifts — could avoid feeling lost. Generation Y, for example — even if each of us had a job and nobody was hobbled by six digits of student loans, we’d still have the shame of comparing our Nickelback to Gen X’s Nirvana. At heart, though, it’s nothing more than a rose-colored effect, juxtaposing reality against a romantic past that never really existed. For artists there’s an added deception. As a writer, sometimes my education feels like an ever-lengthening definition of things I am not, of people I am not, of feats I’ll never achieve. Samuel Beckett, after the publication of Ulysses, spent 20 years fearing there was nowhere left to go in literature. He then published Godot. It’s easy to get so wrapped up in defining yourself and your place in the cultural timeline that your self is all you see.

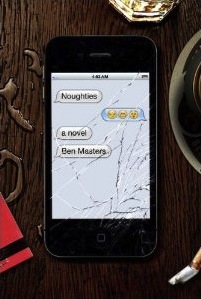

Eliot Lamb, hero and villain of Ben Masters’ debut novel, Noughties, is nearly crippled in this act of defining. “What we are facing here is a problem of conceptualization,” he says:

We just don’t know where to place ourselves, and neither will history. The Roaring Twenties and the Swinging Sixties we ain’t. Can’t be. We resist totalizing models and interpretations… We’re a loose bunch: a confused series of tenuously associated, random events. How will we be referred to? How will they homogenize us? … We have no foreseeable narrative, untaggable as we are. Ours is a lost period, shopping around for identity, spiraling off in referential chaos.

Eliot settles on the eponymous “noughties” to describe those who came of age in the double-ought infancy of the 21st century, “smacking as it does of nihilism and reprobates.” This is one of the countless meditations we’re privy to as his hyperconscious narrative unravels, writhes, and convulses in the span of his last night at Oxford, on the morrow of which he’ll venture out into adulthood, whatever that is. Beginning with the first of many drinks (I lost count) and ending with a professional hangover, Eliot’s final night as a uni student is a constant glancing back at the last three years – from the post-sixth form summer of first love to an increasingly-painful education that goes beyond the intricacies of the English language and into the tangle of human relationships and life on Earth.

Yet for all his supposed nihilism and self-proclaimed untaggability, Eliot’s story is archetypal. No matter how many times he rues modern narrative anarchy, and no matter how many allusions he pepper-sprays into the reader’s face (“I am an Oxonian, but Wellingborough born”; “We are the Judes who would not be consigned to obscurity”; and two points for “Maybe it’s time for some of that Copperfield bullshit”), he can’t hide his most shameful secret – that his account is only the most recent in a long line of stories that hew to a convention as old as the novel itself: the coming of age narrative.

With his dramatic habit of withholding information (“I am unbearably aware of what I’m running from”), his predictable self-deprecation (“There was, for instance, the sexed-up playlist singing instructively in the background… which must have her thinking how white and unsexy I was in comparison”), his recurring and overtly symbolic dreams about an uncomfortably mature baby in a pram, and his narcissism, Eliot could be the narrator of any novel plucked from any student’s bookshelf. His story is no less common – a boy in trouble, a boy in love, a boy who must shed his selfishness to shed his boyhood. But it’s hard to be so cynical. While Eliot struggles to own up to his very average crises – a pregnancy scare, love at the cost of friendship, the post-breakup depression, way too much wanking – Masters has rendered them so honestly that, while cringe-provoking, they cut straight to whatever it is in the heart that remembers what it felt like to lose that first love, or to punch your best friend in the face.

To be frank, Eliot pissed me off within a few pages. Like Holden Caulfield, his juvenilia and his whining beg an exasperated “Grow the fuck up” from the reader. But everyone was young once, and I’m pretty sure that all teenagers hate themselves and blame someone else for it. I’m tempted, when I hear college students in coffee hangouts complain about homework assignments or having to wake up at “nine-fucking-o’clock,” to recommend a few real problems. Similarly, it’s hard for me not to write something like, “Wait until you blink, Eliot, and five years at the same ‘temporary job’ are behind you,” all over Noughties’ margins. But my curmudgeonly scorn doesn’t change the fact that Eliot does feel like the world is ending, that standing at the precipice of adulthood and artistic maturity is enough to paralyze every muscle in your body. There are other people in the world, though, and it doesn’t end for you. When Eliot wakes in the morning to the same dorm room, the same hangover, the same “knowledge of my self,” there’s a hint that he’s finally aware of this—the existence of them to his self. His classmates aren’t confined by definitions, and neither is he. His isn’t a generation of Noughties at all – nor are they Lost, Boomers, X, or Y. The world’s simply full of people, and seeing them as they are is to will that first muscle out of atrophy.

This post may contain affiliate links.