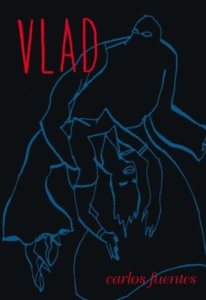

“‘As you know, it’s preferable to be the master of your own downfall rather than to find yourself the victim of forces beyond your control,’” Navarro’s boss tells him early in the story. The deeper we go with Navarro, the narrator and main character of the late, great Carlos Fuentes’s novella Vlad, the smaller becomes the distance between control and victimhood, as they begin to pulse together in a messy, bloody, gradually overpowering confusion.

In Vlad, Carlos Fuentes harnesses the symbolic power of the vampire (needless to say, with much greater mastery than the average specimen of recent vampire mania) to make a brief, slashing incision deep into the fasciae of postmodern society. Navarro is a lawyer in contemporary Mexico City, happily married with a daughter he adores. When his boss asks him to set up a house for a friend who’s new in town — a house with blacked out windows and a custom tunnel dug in the backyard — he doesn’t immediately become suspicious. Soon, though, he is invited to the new stranger’s house, where he becomes better acquainted with Vlad and his “disagreeable elegance” than he wishes to be. Awakening in the night in his own home to find an icy hand wrapped around his ankle is only the first stage of Navarro’s and his family’s involvement with the evil, immortal Vlad the Impaler, the vicious, real-life 16th century dictator who inspired Dracula.

The restrained narrative voice in Vlad only amplifies its thematic complexity, which each sharp sentence unfolds before the reader with precision. Vlad, an Old World kind of guy, likes to reflect nostalgically on the decay of aristocratic society. In an early scene, he invites Navarro to dinner at his house, and muses, “There are some types of families that become lethargic . . . and they settle all too easily for what they refer to as modern life. Life, Navarro! Does this brief passage, this instant between the womb and the tomb, even deserve to be called life?” Vlad’s aristocratic nostalgia comments cuttingly on the Mexican bourgeoisie that Navarro is a part of — but it’s undermined by his tacky-evil-chic style of self-adornment:

As though to illustrate his morbid point, quick-witted Vlad (as in “Call me Vlad” and “All my friends call me Vlad”) walked over to the piano where he played Chopin’s saddest prelude, providing a peculiar sort of divertissement. I was amused by the way his wig and glue-on mustache stumbled with the movements of his performance. But I couldn’t laugh when I looked at those hands with their long, translucent fingernails caressing the keys without breaking.

At first, the story’s violence is only gestured to subtly — the way it plays with life and death, absence and presence, pain and the involved descriptions of sexual pleasure between Navarro and his wife. More pointedly than this perhaps oblique critique of contemporary upper-class culture is the later explicit catalogue of Vlad’s atrocities. When Navarro discovers who Vlad really is, he reads a historical account of the evil deeds he committed in the 16th century. The vivid and grotesque excess of the list both made me nauseous and immediately brought to mind accounts of state terror during the 1980s. Like victims of state torture, Navarro is faced with the corollary horrors of dealing with the darkness left in his mind in the wake of the trauma that hits him and his family. Vlad brings the dark complexity of Navarro’s situation into gritty, palpable relief.

This post may contain affiliate links.