“Far away over the canal towers and gilded domes of Hav, the great grey-gold mass of the castle, looked from that bowered belvedere like a city of pure fiction.”

1.

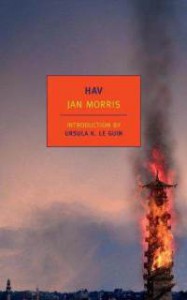

Hav is a fictional travel narrative and in it, Morris mixes fact into fiction like mushrooms into scrambled eggs – if you look for the bits of mushroom, you can pick them out of the eggs, but unless you spend a lot of time scraping, you’ll never get all the egg off. When Morris wrote the first half of this novel, published in 1985 under the name Last Letters From Hav, she was so well regarded as a travel writer people didn’t understand the book was fictional and called their travel agents (LOL wut is a travel agent!??!?) to plan vacations to Hav.

While all novels involve some interplay of fact and fiction, Morris’s has a third layer: fictional nonfiction. In 1985, the internet didn’t live in everyone’s cell phones, so they called their travel agents. Now we can do a quick Google search with the book open next to us. The immediate availability of all common knowledge in contrast to the delicate interplay of real and unreal adds a fourth, subjective, layer to the reading of this novel: what facts you, the reader, know to be true and what facts you, the reader, know to be false.

In Last Letters from Hav, Morris introduces all the splendid peculiarities of Hav the way any travel writer would introduce the splendid peculiarities of a real city. Hav is a mix of cultural influences: Greek, Russian, Turkish, Chinese, and Middle Eastern. New Hav is Western European with separate districts carved out by the French, German, and British. Every year, a bunch of cave dwellers known as the Kretevs harvest a limited supply of “snow raspberries” so delicious they are worth more than their weight in gold and so limited most Havians have never tried them. A statue called the Iron Dog sits, graffiti-covered, near the southernmost boarder of the country. On May 5, Hav holds a yearly Roof-Race, a dangerous sprint across the roofs of the city, possibly commemorating a historical Havian’s sprint (or maybe not, Morris discovers). As Morris wanders through Hav, she references some of the country’s famous visitors: a young Freud, Tolstoy, Thomas Mann, and even (if rumors are true) Adolf Hitler.

Reading Hav forces you to wonder what’s “real” and what’s “fake” while simultaneously realizing that the distinctions between real and fake, true and false, are arbitrary, shifting, and hazy. The Havians Morris meets contradict one another the way people do in the real world. The Greeks claim Hav was built by Greeks and that history has been swept under the rug: they claim the morning trumpeter, previously identified as an Armenian from a long line of Armenian trumpeters, is actually “pure Greek.” Then, a page later, Morris pulls the rug out from under us again:

The more I watched and listened to them, the less Greek those Greeks really seemed to be. There was something odd about them. Were they really Greeks at all? All the externals were there, of course, clerical board to feta cheese, but something else, something more profound, seemed to be wrong.

Morris travels through Hav wondering how deeply she should investigate the locals’ often wildly varied versions of Havian history. Sometimes she pokes her nose where it doesn’t belong; sometimes she backs away.

Should I search for answers, let myself be knocked out by the double punch of Morris’s intricately woven fiction and the ready availability of almost all information? Or just let it be? Despite temptation, I resisted – valiantly resisted! – reading Hav with Google open to avoid interrupting my reading every time I wondered Is this true? and let myself be swept away in the unreality of Hav. I’m glad I did.

2.

The first two hundred pages of the book, Last Letters from Hav, originally stood alone. It is an engrossing narrative, but it now has the dual purpose of providing a contrast to the latter third of the book. At the end of Last Letters From Hav, Morris hears of a growing unrest in the country. She does not understand what is happening, but she senses the rising tide of change and investigates. She leaves before the reader fully understands the implications of impending doom though Morris manages to provide a sense of closure about her first experience in the country.

The gap between Morris’s flight from the country and her return are a flip of a page for the reader, though Morris waited nearly a decade before returning to Hav, returning both as a writer and as a character. The last hundred pages – Hav of the Myrmidons – were added post-9/11 in the real world and post an “Intervention” in Hav. The reader sees Hav literally destroyed and rebuilt, then recast as the historical province of a group called the Myrmidons who are now reclaiming control. The snow raspberries are canned and sold as Havberries, the track of the Roof-Race has been restructured to qualify as an official Olympic game.

At first, the new Hav seems obviously and jarringly false: a place functioning under the kind of agenda spelled out in a press release or thought up during a marketing meeting, like a city of McMansions. But as you follow Morris through the reformed city, you slowly begin to realize that this new Hav might not be so different from the old. In the old Hav, people were always arguing about what the country actually was, what it actually meant. History is, and always will be, the story that the winners (of any kind of war, even a cultural one) tell about the past. The Myrmidons might be commercializing Hav, and destroying the city’s spirit in the process, but their ancestral claim to control has as much validity (or lack thereof) as the Greeks.

Hav concludes with an Epilogue, which Morris narrates as the author of the novel rather than as a character. She frankly discusses the fictionality of Hav, though that doesn’t stop her from setting up another contradiction. Morris admits that she doesn’t know if there is one “essential allegory” of Hav spanning both halves of the book, or if they should remain allegorically separate, or what the book is trying to mean at all: “I can only leave it to my readers, apologetically, to decide for themselves what it’s all about.” Don’t apologize – that’s what we want. We’ve got Google, or the option to turn off of our computers.

This post may contain affiliate links.