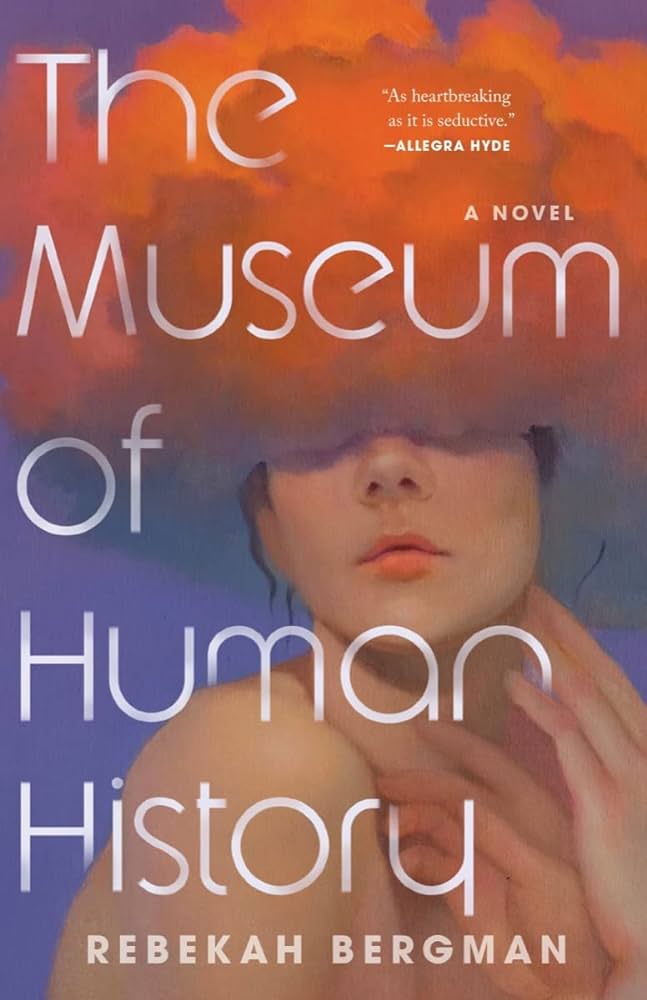

[Tin House; 2023]

Like other recent works of dystopian sci-fi, the broader external conflict in The Museum of Human History is only scaffolding; the central narrative lies in the hearts and minds of its characters. Take for example Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven and Sequoia Nagamatsu’s How High You Go In the Dark. Mandel’s novel focuses on a handful of characters in a post-pandemic world, interweaving their intimate albeit geographically scattered lives as they try to rebuild civilization in defiance of despair and loss. Nagamatsu’s work builds off a more mosaic narrative, becoming more and more insular and self-referential as a virus unlocked from Siberian permafrost changes humanity forever.

Bergman’s novel takes as its scope a singular dystopian city. The metropolitan area is booming due to an emergent biotech industry that, with various projects and initiatives, proceeds to change the lives of its inhabitants and the landscape itself. The fictional city is located next to an ancient human archeological site, in an ambiguous setting resembling the Pacific Northwest. The biotech industry comprises three large companies which are all opening new campuses within city limits. They each promise different things, which various characters meet with both wonder and distaste. All three focus on moving beyond temporality and towards a timeless eternity. As often happens with real biotech companies, these promises turn out to be half-scams and the experiments fail dramatically. A cloned mammoth dies, despite the fanfare of its birth. The first patient to receive a full head transplant dies post-op. A new drug, Prosyntus, marketed to completely stop aging, is found to have devastating side effects: drastically shortened life expectancy and complete memory loss.

The novel both emphasizes and disregards time. Chapters are out of chronological order, sometimes jumping decades into the future. Characters meet but fall out of touch. The novel begins with a memorial for an eight-year-old girl named Maeve who, after almost drowning, is now living in a strange sleep state; she’s not quite comatose, but also isn’t responsive to noise or other stimuli. During the ceremony, it is revealed that it has been twenty-five years since her accident and Maeve has somehow not aged a day. The years passed as her father took care of her, meanwhile neglecting Maeve’s healthy twin, Evangeline. The rest of the story follows a thread of realism as Bergman attempts to illustrate how human memory and connection can stretch through time and turmoil. Following ordinary lives through the peaks and valleys of time’s inevitable march maintains a sense of a shared reality in an otherwise surreal novel.

Bergman’s narrative is not structured linearly nor is it even built with a sense of past or present. Often it feels like the narrator is Time Itself. The prose rips the reader from assumptions of a typical temporal plotline when, for example, we read about Maeve’s parents’ first date: “Naomi Clarke met her future widower.” These jumps in time get more extreme as the book goes on: each chapter is set either months, years, or decades before or after Maeve’s sleep. The slipstream effect of this structure forces an attitude of curiosity and openness to what might happen. Events are told vaguely by one character, but then crystal clear by another. Details zoom in and out of focus as Bergman allows the headwaters of the story to trickle through.

The limits of Bergman’s psychedelic plot structure are tested by using characters who are all seeking a way to flee grief or regret and intersect at key points in their lives. Take, for example, Kevin Marks, the owner of the titular Museum of Human History. The institution, which is always strapped for cash, showcases the remains and artifacts of those ancient humans found at the local dig site. He is obsessed with preserving history, especially his personal history. Having grown up in the shadow of his father and grandfather, he carries the burden of their legacy and can’t quite live up to it. He pursues this concept of historical and archeological preservation—one of the novel’s central questions.

This theme takes on material significance in the narrative through a drug that freezes aging, created by Genesix, one of the three biotech companies recently established in the city. Prosyntus ultimately fails, but not before re-shaping the world. Kevin doesn’t take the drug himself, but befriends and takes care of another individual the reader meets early on, Sylvia Price, who has early onset dementia, a side effect of the drug. Her husband had taken Prosyntus, but passed away due to unforeseen side effects. The lives of the characters go on to be remembered or changed by other characters.

The novel’s prose style itself is in defiance of a very human belief: that an individual must do something in their lives in order to be remembered after it ends. While it is good to preserve the past and remember who has already passed, “The dead did not grow any older while the living must.” Bergman wants to emphasize that our obligations are to those living, no matter how important the dead are. We must choose to be present with those around us. Bergman is not discounting grief; the novel argues that how we honor those who have passed or will soon pass, is a way to live in service of the living.

Kevin and Sylvia embody this idea. Kevin, the director of Museum, visits Sylvia in her nursing home: “[Kevin] told her stories that were really his memories of his life both before her and with her. He used third person and she did not recognize the characters. Not the one who was him or the one who was her.” Rather than try and confuse her further, Kevin frames these stories with nameless characters. He makes the conscious choice to be satisfied with her presence alone. It doesn’t matter that she can’t reciprocate. He loves her. Kevin tells stories of both Sylvia and himself, maybe in vain hope that she’d remember, but also in his own desire to have himself next to her for a little longer.

In the novel, memory is colored by nostalgia and clouded by forgetfulness. Luke, a widower, took Prosyntus when his wife was diagnosed with cancer, since he wanted to “preserve the person he was,” but instead he loses the memory of her entire existence: “when you curate the past, you change it. The story you tell becomes the story that’s told and everything untold is lost.” Our experience of ourselves can never be simply handed to another, even if we wrote it all down day by day, minute by minute. This idea is also exemplified by the great effort Kevin goes to to preserve local paraphernalia in his Museum of Human History. In his climate-controlled archive, visitors can find rocks and other artifacts found at the various digs that have occurred in the area. The pride of the collection is a doll—a boy made of red rock they call “the prince.” After decades, the tragic deaths of Naomi, Maeve, and Evangeline’s mother are remembered by complete strangers and become local history.

Bergman’s novel raises some big existential questions: how does a person preserve their life after death? Should we dare to try? Trying might cause us to become consumed by the pursuit and miss the experience of life itself. Instead, Bergman relentlessly argues that sharing life with those around us is what matters most. Memories exist for other people after those who made them leave or pass away. It’s tempting to read Bergman’s novel as in favor of the romantic preservation of the past exemplified by the Museum of Human History and against the hubris of preserving for the future. But the novel is asking another question. In the face of centuries and epochs, we retain so little. Is there a third option—neither romantic nor technocratic—for holding onto the past? It would be reductive to say that The Museum of Human History wants us to “live in the present,” but in many ways this is what her characters glimpse when they truly encounter one another. Bergman spells out the fragility of our own lives in the face of deep time: “How much time there is but how little is ours.”

This post may contain affiliate links.