The evening after they discovered the tumor growing inside of me, I found myself sitting in my small home office, completing the last bits of the semester’s grading. Seemingly out of the ether, the lyrics of a song came to me: And I know it, I can’t see it / But I know it enough to believe it. I put my pen down, rested my head against the window next to my desk, and closed my eyes. From where did Hole’s “Jennifer’s Body” arrive? Why this song, now? My thoughts were plangent, and as the melody and lyrics continued to run through me, I was transported to the smazy memory of my younger self staring out a car window at a yellowing beach town, mouthing the words, “Sleeping with my enemy myself.”

*

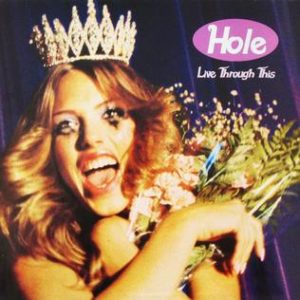

It was in the spring of 1995 that my mother was diagnosed with stage IV invasive epithelial ovarian cancer, and it was late in the summer of that year that I was taken on vacation by my friend D’s parents. I don’t remember much about the vacation itself—a snapshot of bodysurfing, a faint recollection of falling asleep at a late-night screening of Waterworld—but I do recall the car ride from Philadelphia, particularly the music piping through my cheap headphones: Hole’s Live Through This, Rancid’s Let’s Go!, a sample CD from the College Music Journal featuring songs by Teenage Fanclub and the Circle Jerks that fascinated me. The interstate became clogged and dusty, two-lane, and as I sat in my office, I could recall the intermittent view of a wave rolling toward shore interrupted by rows of stilted clapboard vacation homes, all while Courtney Love wailed, “Make me real, fuck you.”

It was in the spring of 1995 that my mother was diagnosed with stage IV invasive epithelial ovarian cancer, and it was late in the summer of that year that I was taken on vacation by my friend D’s parents. I don’t remember much about the vacation itself—a snapshot of bodysurfing, a faint recollection of falling asleep at a late-night screening of Waterworld—but I do recall the car ride from Philadelphia, particularly the music piping through my cheap headphones: Hole’s Live Through This, Rancid’s Let’s Go!, a sample CD from the College Music Journal featuring songs by Teenage Fanclub and the Circle Jerks that fascinated me. The interstate became clogged and dusty, two-lane, and as I sat in my office, I could recall the intermittent view of a wave rolling toward shore interrupted by rows of stilted clapboard vacation homes, all while Courtney Love wailed, “Make me real, fuck you.”

It was a rasping demand that I appreciated back then. My mother spent most of her time in bed or on the couch, gray and vomiting and suddenly hyper-religious, while my father worked in the day and spent sleepless nights caring for her. His parents lived with us for a while. Besides games of Scrabble and gin rummy, we all found few ways to bridge the gaps between us. I had friends, of course, and their well-meaning parents who carted us around to various activities or allowed us free reign to run around, but none of it mattered to me. It all seemed like a prefab distraction to which I was supposed to resign myself. Because I couldn’t shake the feeling that it was a well-meaning ruse, I also couldn’t slough the inkling that there was something deeply wrong with me, that I was an unreal target of an immense plot.

In my head, the vacation with D and his family remains at the center of this plot, of this whole time period, even though many specifics of the time near the seaside have slipped away. Other than the music that obsessed me, my sharpest memory of the trip is when, during the last slog in the family sedan, I proclaimed that Courtney Love was a genius. For a moment, C’s mom and dad looked at each other. Then one of them dismissed my enthusiasm by denigrating Love as “crazy” or something similarly pejorative.

The contemptuous tone of their reaction solidified what had already been congealing: that my dim view of my circumstances as a being in this world would never be recognized as legitimate, and that the conspiracy of distraction was not imagined. I was not presumed to feel anger, pain, or bitterness, and when the extraordinarily vivid reality of those emotions came to the fore, they could be discarded by others as easily as my expressions of joy and exuberance, of identification. I put my headphones back on: No one cares, my friends.

*

I’ve never been able to accurately describe the feelings that I felt then. Even now I find the depiction above inadequate to a degree matched only by the poor consolation that had been offered. It made me gasp, then, when I was reading through the recent “shorter” edition of The Norton Anthology of Short Fiction during class prep and came across Alice Munro’s story, “Miles City, Montana.” Within the first two pages, a local boy dies tragically, and the child narrator finds herself looking at the adults at the boy’s funeral with “a furious and sickening disgust . . . [that] had nothing sharp and self-respecting about it . . . It could not be understood or expressed, though it died down after a while into a heaviness, then just a taste, an occasional taste—a thin, familiar misgiving.” What Munro’s narrator discerns in herself is a bile and rage marked by an obliquity of reason, yes, but it is not entirely directionless—the adults are culpable in some nefarious act, and they seem undoubtedly deserving of the narrator’s scorn. But the specifics of that act, however familiar it might be, remain mysterious.

After reading this first section of Munro’s story, I let the weighty book fall from my hands, onto my chest. What was this intimate act that so troubled her narrator, that so disturbed my own sense of well-being as a child? How did her narrator manage to respond to this not-knowing the source of her own anger? How did she survive? How did I?

In an entry included in the introduction to The Cancer Journals, Audre Lorde writes that there is “no device to separate [her] struggle within from [her] fury at the outside world’s viciousness, the stupid brutal lack of consciousness or concern that passes for the way things are.” This illuminates part of what is happening to Munro’s narrator, and what was happening to me in 1995, albeit under very different circumstances. The inextricability of which Lorde writes is matched by, and might be constitutive of, the “heaviness” that Munro’s narrator feels. That this feeling can lead down many labyrinthine paths wracked by suffering is a given. How these paths fascinate and sustain, though, is what should most interest the living.

Thus, for me, punk rock was never about skateboarding or a modish hewing to outlandish fashion choices. It was about a firm belief that there was a senselessness to what caused both the familiar—the “struggle within”—and the ever-shifting machinations of the world around me. My own furies, confusions, and happinesses were rendered immaterial and unreal by the people with whom I interacted, and those same people seemed petty and oblivious regarding the brutalities punctuating the world beyond their doorsteps. No wonder I felt like an alien, and no wonder Love’s exhortations—“Make me real, come on,” with a pronounced increase in throatiness on the three final syllables—initiated me into a realm where demanding the impossible was viewed as perfectly reasonable.

In returning to “Miles City, Montana,” Munro’s narrator, now an adult, recollects her younger self viewing her parents at the neighborhood boy’s funeral:

I was understanding that they were implicated . . . They gave consent to the death of children and to my death not by anything they said or thought but by the very fact that they had made children . . . even then I knew they were not to blame. But I did blame them.

It would be easy to say that Munro’s narrator was in rebellion against death, but really, she was in rebellion against “effrontery, hypocrisy,” against the snares of “vanquished grownups, with their sex and funerals.” Like punk rock, it is an impossible rebellion, but one with a sincerity of feeling, veritably drenched in empathy—righteous and perfect in its righteousness. It raises its fist against the “stupid brutal lack of consciousness” that Lorde decries, and which made me so miserable as a child. I wanted honesty, and what I got were adults trying to shield my eyes from nurses plunging needles filled with poison into my mother’s flesh, adults attempting to find new routes so as to not to expose me to the collapsing, abandoned houses in mostly black neighborhoods stretching for miles in our home city, adults steering me away from the profane and defiant because they were frightened of the real and wanted to pass that fear on to me. And because I wasn’t having what Born Against’s Sam McPheeters calls the “smiling commodity that isn’t human,” I can still see myself alone in my room at age eleven, alone in my room at age 13, alone in my room at age 14, whirling around and mouthing lyrics to shambolic, naive, pissed-off songs that won’t ever get old or die.

*

A little more than a week ago, on my first day of chemotherapy, I found myself alone in my infusion suite, a bit of a throb emanating from the IV in my right arm. In my left hand was a copy of Light Sweet Crude, a book of collaborative poems and lyrics by Vancouver poets Nancy Shaw and Catriona Strang. I’d become slightly obsessed with Shaw’s work during a trip to Vancouver last fall and had received the book as a Christmas gift right after my tumor had been biopsied and diagnosed. That Shaw had passed away from cancer in the middle of her collaboration with Strang was a fact not lost on me when I unwrapped the book on Christmas Eve, nor was it lost on me in the antiseptic yet cocoon-like warmth of the suite where life-saving poison dripped into my arm.

Yet again I gasped, for as I approached the book’s end, I noticed liberal quotes from Courtney Love’s lyrics to “Violet” and “Olympia” smattered throughout the text much as they are smattered in this essay. The songs, which had meant so much to me as a child and which had been reverberating in my head since the day following the discovery of my tumor, proved a perfectly sly inclusion in a group of poems determined to interrogate and engage with the sublime, “its envelopment of the beauty and/or horror of the self, nature, war, kindness, passion, and disaster.” Like Strang and Shaw’s work, Love’s lyrics embrace contradiction, particularly with regard to visions of the self, putting the lie to the myth of the unified subject. The book, which had been pretty wonderful in the minutes before, became exciting, and then it became something else.

It was when I reached “www.sorry.com,” a late poem in Strang and Shaw’s “Cold Trip” sequence, that I began to weep, to wrap my head around my more pressing and present mortality. Here it is:

My sincere apology

I repeat, I was

Roving very fast

Set my pulse

To obsolesceI’m the one with no soul

I told you from the start

How this will end

I lament my fate

As sentimental hateLove stops innocence

Journey and curve

The apology, you answer

I cannot talk more than usual

When clouds deny twilight

To close the distance

Measured in liesDespite the times

I will illuminate

Weeks of withering

Witnessed in every single line

We look the same

We talk the same

My dear supportersThe purchaser sells the sky

Is this progress

You know it’s all

Squandered

As a consequence

You brighten up

That I thought

You would flatter me

The poem astounded me and astounds me continuously. It begins with an apology, appropriate since an expression of regret is usually the first phrase that leaves peoples’ lips when confronted with illness. Strangely, the apology is often mirrored by the sufferer and becomes part of a recursive phrasal economy of mutual sympathy— an infinitude of “I’m sorry”s resounding through all interaction. My partner, my mother, my father, my friend, even total strangers are all sorry, and I am sorry that they are sorry, and it pains me that we are so filled with sorrow because of this growth that is inside of me that none of us could have predicted. I would that our sorrow could be channeled elsewhere.

The poem then moves quickly through implications of fast living and planned obsolescence to Gins-like rejoinders against the reaper, arriving at the first insertion of Love’s lyrics. Here we are confronted by the afflicted person’s acquiescence to the societal demand that the sick individual has “no soul” and only sickness, a demand that is particularly onerous when mortality is part of the equation—even if the afflicted individual knows “how this will end,” society craves the sick person as an emblem of noble suffering, soulless as the person might be. Many who are placed in the position of the ill patient lament this treatment, as it makes manifest a contradiction—the suffering person is both monumentalized and despised. That so many cancer patients see a few good friendships drop off after their diagnosis is certainly evidence of this latter characteristic that defines even intimate views of the afflicted body.

We are then granted a return to the apology, its recursion becoming more evident, but here made slant by love (or Love?) and its habit of forcing culpability onto the afflicted subject and sympathizers alike. What is this guilt? I read Strang and Shaw’s words as suggesting that it results from the haziness of the distance toward death—“clouds deny twilight”—but there is also the closeness of that distance, particularly for Shaw, and it is “measured in lies” that deny that closeness as a result of love. The afflicted does not want to quit love, and neither do her sympathizers, and so both resort to lies to keep the body wrapped (and rapt) in the intransigent yet intimate bonds of love that can only be found in platonic friendship. What my younger self desired was exactly what Strang and Shaw seem to be doing here: acknowledging the lies that abound in the relations between those who are ill and their families, friends, and associates. The acknowledgment doesn’t diminish any feelings of tenderness and affection; instead, it serves as a method of viewing the distance between the now of illness and the far (or near) place of mortality.

And then there are the lines of Shaw and Strang’s poem that most buoyed me, these lines that forge a determination and a continuing: “Despite the times / I will illuminate / Weeks of withering / Witnessed in every single line.” It is difficult to have cancer, yes, but it is also difficult to have one’s cancer constantly framed in bellicose terms, especially when one is not a bellicose person. Thus, that the lines frame the “witnessed” documentation of “withering” as part of a process of illumination gives solace, because while I remain that furious alien teenager in many ways, my diagnosis finds me more interested in illuminating as a form of yelling. Love arrives again, too, and becomes part of the admonishment not just to “dear supporters,” but also to the wider world, transforming Love’s alienation into a unifying rally, “We look the same / We talk the same.” There is, too, the suggestion that in the end, we are these fleshy husks, that there is a flattening of difference that comes when our bodies turn cold

I can’t imagine a poem closer to my complex of feelings as I sat in that curtained-off zone, the crackle of TV babble from other patients nearby, the smell of Chinese takeout wafting the floor’s corridors. I realized that part of why I’d wept while reading it for the first time was not only the synchronicity of its message with my surroundings and the linkages of cancer and illness strung between me with Shaw, but also the rage that I share with both poets. It is not an easy anger, but it arrives from empathic nodes, from that space that does not want to be sick because the world is sick enough, and there is forever the compulsion and need to challenge such sickness. As I’d walked into the medical building that morning, I’d passed by a homeless man begging for change, coughing something terrible. Though my privilege has allowed me the modicum of comfort that shitty insurance provides, the conditions that create his sickness are the same that create mine, and neither of us should have to shoulder the burden of this agony.

But my body suffers, the bodies of so many others suffer, and I only have so many methods of placing blame for that suffering, for the “squandered” world I inhabit for now. One of those is crying and another is crying out, and so I will do both heedlessly into the indeterminacy of the months ahead.

1/24/19

Ted Rees is the author of In Brazen Fontanelle Aflame (Timeless, Infinite Light 2018), which Publishers Weekly called “a sort of hybrid queer, ecopoetic, intertextual manifesto.” Other recent work has appeared in Mirage, Tripwire, and ON Contemporary Practice’s monograph on New Narrative. “Against A Beige Vision,” an essay on Oakland’s poetry scene and the Ghost Ship tragedy, appeared in Full Stop Quarterly #6.

This post may contain affiliate links.