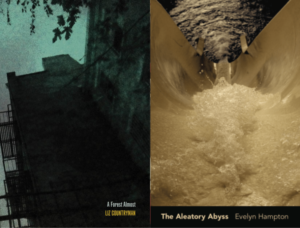

[Subito Press; 2017 // Publishing Genius; 2017]

[Subito Press; 2017 // Publishing Genius; 2017]

I read somewhere recently (where? when I Google it now there is an unsurprisingly large number of hits) that our current collective unhappiness is simply (“simply”) the result of our inability to believe in the future. That dis-ease is right, right? When was the last time you could comfortably toss your thoughts beyond the upcoming decade? (A responsible, gainfully employed friend, when asked if she had started a retirement account, laughed a huge laugh until sludge came dripping out of her mouth.) So, yes, future plans have melted into bitter tar. But the symptom’s misnamed.

The inability to believe in the future, a failure that we humans have made possible — we have exceeded ourselves, haha! — has created, not unhappiness, but ____________________. I’m taking that blank from Liz Countryman’s book of poems, A Forest Almost. She describes the unspeakable symptom in her poem, “The First Time We Felt What Was Later Diagnosed As ________________,” which, like many in the book, teasingly brings you right up to the abyss, but won’t tell you what you’ll find when you look. It just makes you look:

It was like the car passing by the Perdue chicken factory

on our way to the beach. It was like the jellyfish

all over the gray beach like boils.

It was like biting into a jellyfish expecting it

to be a gummy bear. It was that hard conversation

staring out into the black waves with Dad. What

death was. It was all wet and hard and it never dried.

It was like an accident. It was like our assholes

were eating themselves. . .

The most definitive thing I can say about that blank, the whatever-is-blanker-than- unhappiness, is that I trust the blank. The ineffable is not so easily trifled with.

But you have to try. Countryman does it by singing, laughingly/knowingly/lightly, in her debut collection. And Evelyn Hampton does it, in her long essay The Aleatory Abyss, by screaming, silently, so that no passerby can detect her acute breakdown. Reading these books during a dark December twinned them in my mind. It may not be fair to either, but I want to talk about them together.

First, Hampton’s patient, platitude-less meditation. It takes place in Oregon, where she is living on the outskirts of a mall and working at a community college, and its topics are trash, squatting, and homelessness in many senses of that word. It’s a quiet book… the kind of quiet a spider emanates when it senses a large object moving toward it with a blunt instrument.

An image of Edvard Munch’s The Scream seems to overlay Hampton’s paragraphs, and Chapter 6 begins with a list, delivered flatly, that points to Munch: “Hobbies: Making slow progress toward figures in dreams. Driving. Pantomiming an ongoing scream.” There’s a sense of disassociation here that the word pantomime invokes: gestures mimic or approach emotions, but a flat, protective numbness prevails, like when Hampton describes a red sunset (one that matches the sky in The Scream): “It looks like bad dye, something that if you eat it will give you tumors. But to look at, it’s lovely.” It’s like, yes, a lot of what we ingest is colored with carcinogens, but hey, modern life is nothing if not a damaging collection of expertise and knowledge that we ignore in order to survive.

Munch described the genesis of that painting, the real title of which is The Scream of Nature: “I was walking along the road with two friends — the sun was setting — suddenly the sky turned blood red — I paused, feeling exhausted, and leaned on the fence — there was blood and tongues of fire above the blue-black fjord and the city — my friends walked on, and I stood there trembling with anxiety — and I sensed an infinite scream passing through nature.” Passing through is an idea that comes up a lot in both books. Hampton’s essay is her passing-through identity as a composition instructor: “I am an adjunct. Masking tape holds my name to the door of the office I share with someone who is never there when I am.” It also chronicles her drives to and from work, her friend Mark Baumer’s walk across America (“His goal is to get to the other side of something”) and her own walks through malls and parking lots to get “home”:

Exiting the mall I immediately enter the parking lot. Home, a low complex of apartments, lies across a distance I have trouble gauging with any part of my body because parking lots are not built on the scale of bodies but of machines with internal combustion engines . . .

And later:

The place where I am living is the kind of place about which I would think, were I passing through it on my way to the place where I live, I would never live there.

I am both passing through a place where I would never live, and living in the place where I would never live.

But as she’s walking through our strip mall landscapes, Hampton wants to feel. She describes the garbage in each parking lot’s perimeter as “something holy.”

It is one holy thing that has blown apart into fragments. Pieces of lost speech, bygone language. I think of Avelokitsvara, the deity who, upon hearing the cries of sentient beings, burst into thousands of pieces, then wandered the earth collecting them.

What on first read I would have described as (“simply”!) numbness in Hampton’s essay is actually, I think, a yearning to feel as deeply as the situation warrants, and not to be destroyed by that feeling.

Countryman’s collection, too, is marked by a passing throughness, a failure to feel: The opening poem includes these lines: “We went through the woods but they passed by us / like a cheap haunted ride.” Overall, numbness is a pretty lovely state (“to look at it’s lovely”) in A Forest Almost. Like watching a horror movie with the Pines of Rome dubbed over it. She nails the impenetrable sensation of distance: “yes — / so we were figures / held apart by dapples, // there was stillness of a Saturday, / the trees browsed each other.” I love that verb “browsed” there: the casualness of looking, life as a series of fine distractions that empty us. Or a serious of fine distractions that help us survive it?

Countryman’s fantastic sense of pace matches the way that modern bodies are moving ostensibly untouched (except for legions of poisons crossing each placenta & in our water; except for car accidents; except for bullets; except for, I mean, everything, everything) through time:

the dark sea’s constant sound

my stupid shorts

our little

hands in conversation

but courage is a move

through fear

your face blows back on a speedboatand the land seems to move toward you

you seem to control it

the steadier your face

the farther back the joys

its skin shields

a simulation of largeness

we go fast and shoot things and call it fun

Nearly every Countryman poem verges on intimacy — she is asking for impact — and then demonstrates its impossibility. The book ends:

This was when Dooley was still alive,

before I first clicked save. Cars rushed

through greens, and the greens did

something in the dark. But I never walked

into them from the highway, I never

met them the way I wanted.

When I say I want you, this is what I mean.

When she says she never walked into them, I’m not sure whether she means the greens or the cars. Probably the greens, as that’s the last noun mentioned. but also this book keeps undermining my sense of okayness with its awful pronouncements. It keeps teaching me to stop trying to think safely. So I’m going to interpret that line as “cars”: she never walked into the cars from the highway the way she wanted.

Impact — an occasion to deeply feel — is also a crucial point in Hampton’s essay. Mark Baumer, whose walk she chronicles in the first half of the essay, is killed by a car on his 101st day crossing America. (I cannot say “passing through” to describe what Mark was doing, because he walked barefoot. His feet felt each step.) Around Day 79 of his walk, Hampton writes,

In Ohio, calcium chloride — road salt — cuts the soles of his feet . . . He keeps walking. He makes records of garbage, old signs with most of the letters missing, stuff nobody else sees. I think of all the garbage between us, the discards lying between our bodies.

And then,

When the SUV hit him his body blew apart into a million pieces of garbage. That’s my friend, down there in fragments. I’ll wander for the rest of my days. I’ll collect him. He has become they. He became too many to live. He had to split apart, break open.

It’s absurd for me to write anything after that paragraph.

But I guess that’s the point of these books?

Just keep going, as if nothing just happened.

Or as if safety or something else nice, were a certainty.

Hampton’s best line comes a few chapters before Baumer’s death, but haunts the whole essay: “I want to be able to hold all the garbage.” While it may aspire to be nothing but personal, The Aleatory Abyss is some kind of Ouija board for the scream that is nature’s. She is slowly spelling it out. And Countryman’s is the scream you take for a breeze through the trees, and then unsettingly and briefly recall as you scroll through the newspaper the next day:

I keep thanking what’s idle when something

is missing:that facade by the field, its building

ripped out (like it waswhen you lived here), held up by steel rods

for no reason,its wreckage snowed and ogled all over, might

kill itselfjust to get you to come.

Or is only getting older.

Again, probably not right to review these two books together, but they both put their fingernails into the same part of my brain. And then, this is too neat, but: The authors’ last names are both places. Hampton’s of course is home, and Countryman’s is a wide-open land. Absolutely wrong for each of their books, but it’s lovely (in that numb, browsy sort of way) that each contains place names, because these books are really the land where we live now. The Land of Numb. State of Pale Facsimile. Facade Address. Passing through to…nowhere really, because if we’re honest (don’t be!) (or as Countryman writes, “Please give me your blessing, thing I live by ignoring”) the future is very blank. But I do, while I’m here, want to be able to hold all the garbage. I want to be able to hold all the garbage.

Darcie Dennigan writes poems and plays. Her fourth book, The Parking Lot and other feral scenarios, is out from Forklift Ohio in September 2018.

This post may contain affiliate links.