[Slope Editions; 2014]

[Slope Editions; 2014]

Memory could be the most personal universal experience. My book club and I finish reading Lydia Davis’ translation of Swann’s Way. At our meeting, when I read Proust’s last sentences aloud, including, “The memory of a certain image is but regret for a certain moment,” my friends Jon and Alex show me the sentence in large font on the back covers of their teal Penguin hardcover editions, as if the book has earned the right to blurb itself. I had called attention to the same sentence as the Penguin editors and likely millions of readers before me. “The memory of a certain image is but regret for a certain moment”: for each new reader, it’s a knock upside the head.

Past, home, memory, regret fuse into an unavoidable cloud in An Instrument for Leaving, winner of the 2013 Slope Editions Book Prize (selected by Dorothea Lasky). American poet Monika Zobel writes about her new life in Germany, but slips into old versions of herself and her family, choked by the consequences of leaving.

In the poem “One Way (Bremen-NYC),” she awaits her plane and reads a note from her father: “Whether or not you return you will / return.” Wheels leave the tarmac.

Yet An Instrument for Leaving is evidence Zobel never left. With each line, she flies back and forth across the ocean, returning to “abandoned swimming pools,” an attempt to atone by reshaping, to re-author the past.

Titles: “An Inventory of Things Lost,” “On the Corner of Guilt and Ash,” “All Ghosts Have Been Accounted For.”

The common myth about the past is that it’s over. It’s not. It’s open to reinterpretation. Past as putty, to shape as one chooses. Roll it back into a ball and pose it again. And again.

The short sentences of Zobel’s poems rely heavily on personification. Abstract nouns replace the tactile: “Sunday clips its nails / on the pavement” or “Preheat the boiler to future failure.” What could be mundane nostalgia, such as a catalog of childhood memories in “We Turned Orange After Eating Carrots,” becomes a demonstration of this posing, the past splitting from reality. The “kale simmered on the stove” but also “licked the pork.” Zobel’s father “swatted / flies with his mustache,” as in he removed it from his face to use as a weapon. On the page, Zobel’s memories become psychedelic portraiture.

The adage: “You Can’t Go Home Again.” Home changed. You changed. Ideas of home stretch. They depart from the reality of a place (its chipping paint, new traffic lights) and form a narrative based on abstraction, somewhere “Where The Heart Is.” Home as the benchmark. Home as a canvas.

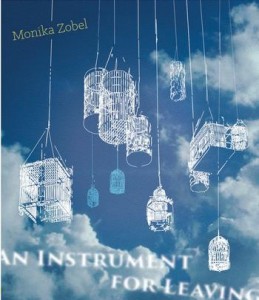

Cover image: Cumulus clouds on sky, night blue. Silhouettes of antiquated birdcages dangling from an unknown source. Cage flat on cloud. The words An Instrument for Leaving already fading into sky.

How many flights over the Atlantic on a given day? Carrying how many travelers? Carrying on how much guilt? Does regret know flying over Iceland is the fastest route? Did the plane leave, or like Proust, like Zobel, am I in a holding pattern over my hometown?

“Whether or not you return you will / return.” No such thing as one-way trip. Zobel says, “I was born in the first century of guilt.” I think guilt’s older than that.

In a fragment from Proust not used as jacket copy, he says we hold “a fetishistic attachment to the old things which our belief once animated, as if it were in them and not in us that the divine resided.”

Zobel says, “My skin already erects / a halfway house for memory.” The self not as divine, but as a site for memory’s reintegration into society. Is memory a criminal? If so, what was the crime? Or is memory a substance one can abuse? Can nostalgia in any form, whether stemming from desire or regret, qualify as overdose?

Years ago, I drove to the beach with friends. We saw a biplane over the water. It flew straight up, then cut its engine. Three seconds of free fall. It rescued itself, spun and looped. It was the day before an air show and this was rehearsal. Is this what I look like when lost in memory? Like a stunt pilot who needs more practice? Are my haphazard loops divine?

Patrick Gaughan is a poet, performer, and critic living in Northampton, MA. He interviews artists and writers for BOMB and The Conversant. Find recent writing in HTMLGiant, Coldfront, The Volta, Entropy, and Blunderbuss. He’s the writer and director of Fast Five, coming this fall from the Connecticut River Valley Poets’ Theater. [tumblr] [twitter]

This post may contain affiliate links.