I have nothing against e-readers: I do not own a laptop or smart-phone either, nor have I ever owned an iPod. I was the last of my friends to have a cell phone, I’ve never used public wi-fi, and my social media presence is slight at best, though I have recently started blogging from time to time.

Like others in similar situations, I could give you many reasons why all this new media hasn’t excited me to buy: it’s too expensive, it’s constantly changing, I’m still too attached to the materiality of texts and music, I don’t want to further enrich already wealthy companies like Apple and Facebook. And then, of course, there’s the certain trendiness that comes with being a “luddite” (which is a term that today gets applied to everyone from vehement enemies of computing to passing internet users), with its connotations of retro-chic and anti-consumerism.

Back in April, in an op-ed in the New York Times, novelist Ann Patchett revealed herself to be a “luddite” in the original nineteenth century sense of the word: that is, somebody who actively opposes the machines that will replace her. This year, as most readers of contemporary fiction know by now, the Pulitzer committee declined to award its coveted prize in fiction, opting instead to recognize three finalists—David Foster Wallace’s The Pale King, Karen Russell’s Swamplandia, and Dennis Johnson’s “Train Dreams”—a move for which Patchett scolded the committee thoroughly. Most readers hearing the news will “just figure it was a bum year for fiction,” which, she claims, is a disservice to writers counting on the prize to drive sales. Fellow novelist Michael Cunningham, one of three jurors who sent nominations to the committee, echoed Patchett in the online edition of the New Yorker: “A literary prize is, at best, one way of drawing readers to a book that deserves more serious attention […] An American writer has been ill served and underestimated.”

Although the prize has been withheld at various times in the past, Patchett sees this year’s withholding as a particularly egregious oversight on behalf of the committee, a literary institution, we are meant to understand, that should be doing everything in its might to stave off the traditional book’s cultural decline (she remains unclear, however, on how elevating one single work above the rest is supposed to safeguard all of commercially-printed fiction.) Of course, if the book is in decline in the first place it’s because of new-media-addicts who have lost sight of the importance of reading. “Following complex story lines stretches our brains beyond the 140 characters of sound-bite thinking,” Patchett writes, “and staying within the world of a novel gives us the ability to be quiet and alone, two skills that are disappearing faster than the polar icecaps.” Equating this generation’s media obsession with global warming is hardly a subtle rhetorical movie, nor is it an effective one: it is easy to imagine that the book industry, at its peak, was responsible for vast deforestation, and that new media technologies, as they get more sustainable, will soon have little carbon footprint.

We might say that Patchett is stuffy or just bitter that her novel, State of Wonder, did not even make the shortlist, but her alarmism over technology’s creep into our culture is telling of greater trends. She is by no means the only writer with “luddite” tendencies, nor is she the only one to be apocalyptic about it; and in some ways this attitude is to be expected from a group of people who believe that society is headed for a crisis after which their skills as storytellers will be obsolete. In fact, what might be slipping more quickly than book sales is the confidence that the vanguard of contemporary literature has in conventional fictional forms.

In steps Jennifer Egan. A little more than one year Patchett’s senior, Egan is, at the time of this writing, the last winner of the Pulitzer in fiction. The final two chapters of her prize-winning story cycle, A Visit From the Goon Squad, leave little doubt that Egan shares an end-times view of the fate of literature. But instead of shouting from the sidelines, Egan allows herself to challenge these concerns in her work.

Indeed, earlier this year in the New Yorker’s science-fiction issue, Egan published “Black Box,” a story written in sentences of 140 characters or less. Then, over the course of nearly a week, @NYerFiction proceeded to tweet that story, a dystopic second-person thriller about an android spy posing as a call girl. In turning toward science-fiction and sci-fi forms, Egan is exploring new possibilities for literature in an age when technology and new media are competing for the book-reader’s attention. But even more, Egan’s recent sci-fi excursions expose her not as a writer resigned to the waning importance of literature, but as a literary “luddite” willing to take things to the next level, to begin a sabotage.

* * * *

In terms of plot, “Black Box” is a relatively traditional sci-fi story of human individuality in revolt against a mechanized society. Egan stated in the New Yorker podcast that the unnamed protagonist is in fact Lulu from the outlandish last chapter of Goon Squad, “Pure Language,” and that the events here take place ten years after the end of the novel, in the 2030s. In “Pure Language,” Lulu is the poster-girl of an imagined new generation, a whiz with technology and marketing, steeped in the lingo, and yet with an almost 1950s naïveté: she has no tattoos, she doesn’t use drugs, she doesn’t swear, and her only passion is money (uncommon traits for somebody working for a punk rocker.)

But in “Black Box,” Lulu is radically transformed. We find her working for the government, on the biggest (and only) mission of her life, posing as a call girl so that she can infiltrate an inner-circle of foreign enemies of states. Her wholesomeness has become devout patriotism, and her body has been consumed by the technologies she once mastered: the state has placed cameras behind her eyes, a discreet microphone in her ear, and a record of field instructions in a microchip beneath her hairline. Presumably, the latter is the origin of the tweet-like dispatches that make up the story.

It’s true that writers less-decorated than Egan have been experimenting with Twitter lit since the site launched a few years back, but in “Black Box,” Egan uses the limited and piecemeal nature of the Tweet not just as constraints, but as tonal guidelines for the narrative voice. Whether the dispatches are from Lulu in the field back to headquarters or vice versa remains delightfully unclear. Moreover the second-person imperative tone of the story lends each sentence an aphoristic quality, such that they might be read not as dispatches at all, but as an internalized set of rules about how to be a spy, a woman, and a patriot.

Indeed, a complicated system of authority emerges over the course of “Black Box” as we learn the full extent of Lulu’s devotion to her mission. Just as her body is grafted with machines of espionage, it also becomes a place for grafting gendered expectations: she must wear gold heels, must have tanned feet, must be innocuous, must register as “young,” and must wear a sundress “widely viewed as attractive.” Later, while her “Designated Mate” violates her, Lulu must practice a dissociation technique so as not to appear uncomfortable and break the illusion of being a prostitute. At inopportune times, Lulu’s mind turns to her husband back home, and she must remind herself that he is a fierce patriot and proud of her for undertaking this work.

There is a clear subtext of domestic power relations here, and what Egan accomplishes with the sci-fi genre, which allows for worlds where people have become mechanized, is to expand the possibility of other intersections between the individual and the greater world imposing on her: the body is intertwined with machinery just as marriage is intertwined with national security. Driving these conflations is a brand of patriotism called the “new heroism,” which the disembodied narrator goes on to describe:

In the new heroism, the goal is to merge with something larger than yourself.

In the new heroism, the goal is to throw off generations of self-involvement.

In the new heroism, the goal is to renounce the American fixation with being seen and recognized.

In the new heroism, the goal is to dig beneath your shiny persona.

The “new heroism” seems to stand in opposition to the technological self-absorption we see at the end of Goon Squad, but the conscientious reader must take the narrator’s edicts with a grain of salt. The “new hero” is asked to be more servile than selfless, a condition, Egan suggests, to which human beings are naturally averse. When Lulu downloads confidential information from her target’s computer into her brain, she must make room for it by wiping her own “confidential information”—memories of peeling an orange for her husband, of the smell of her childhood cat and her mother’s peppermints. “Your physical person is our Black Box;” the voice reminds her, “without it, we have no record of what has happened on your mission.” Lulu has given not only her body to her country but her memory as well. She has become the “new hero,” a body free of a self, in service of nothing but the greater good.

Lulu gets caught in the act, and, while a “goon squad” chases her down, she finds her memories persisting in the back of her mind (the persistence of the past is a major theme of Goon Squad, as well). “Hindsight creates the illusion that your life has led you inevitably to the present moment,” the voice says. Lulu has not managed to efface all traces of her memory. The story’s central thematic tension comes to be between the impersonality necessary to being a spy and the inevitable persistence of a personality.

The “new hero,” as prescribed, is an impossible figure, and the “new heroism” might not in fact be the best form of resistance to the “American fixation” that we see Egan cynically exploring at the end of Goon Squad. The future she gives us in the last chapters of that book is one of instant-gratification where personal electronic devices have bred an uber-“Me”-generation of babies who learn to use iPods before they even learn to walk, and where, it’s safe to assume, the importance of reading long, serious fiction (the act that the reader is just now concluding) is lost. On the other hand, the future she gives us in “Black Box” is one where the dominant mode of selflessness is a cult of utter soul-crushing service to the nation-state. Again, it’s likely that nobody is reading novels in this future, either.

It is the “hero” who actually emerges in the character of Lulu that Egan has staked her bet on. She is a flawed hero who blows her cover, who lets pesky sentiment get in the way of completing her mission. And yet, at the same time, she stands as the triumph of the human against the dehumanizing forces of the world, be they technology, the nation-state, an unequal marriage, or socially constructed femininity. In essence, Lulu is just like every successful protagonist in literature, all-too-human. The “new heroism,” for Egan, is really just humanism.

* * * *

If science-fiction exposes the underpinnings of our contemporary society by projecting them into the future, then Egan is arguably presenting this “new heroism” as an ethic for today. She certainly has her reservations about the behaviors that new media promote—maybe we could stand to be a little less connected, a little less self-absorbed, a little more wary of a touch-pad’s educational value for our children. But instead of resisting, Egan adapts her writerly work. She seeks to tease out the human element in new and apparently anathema forms.

In discussing “Black Box,” Egan explained that for a while she had been interested in using Twitter as a means of publishing serialized fiction, as was popular back in the nineteenth century. But Twitter-ized fiction can do two important things that nineteenth-century serialized novels could not. One, it can infinitely extend the dissemination period of a story, and thus incorporate a cliffhanger (the engine of a lot of popular fiction) at every level: an author could go so far as to Tweet one word a day, though serialization this extreme might prove alienating. Two, it can find its way into the fabric of our days surreptitiously, and with much less fanfare.

The former might become interesting to writers hoping to learn how gratification and its delay function in storytelling, while the latter might become interesting as a marketing strategy. Egan has already experimented with this latter re-branding of fiction by implicitly asking, in chapter 12 of Goon Squad: what if, instead of reading aloud, authors presented their chapters or stories as slide shows before a group of “readers,” injecting literature into the quotidian setting of, say, the business conference?

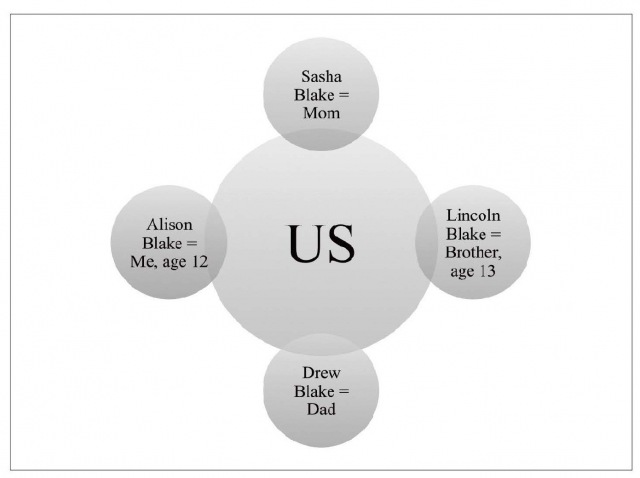

Maybe one of the more touching chapters in the book, “Great Rock and Roll Pauses” takes place in the 2020s and is told from the point of view of twelve-year-old Alison Blake, in the form of her “slide journal,” a Power Point that resembles a class presentation. We gather that traditional writing is no longer taught in schools, but that students learn to make slides like this instead, and Alison irritates her mother by repeating the marketing advice that she learns in school, sayings like: “Charts should illuminate, not complicate!” and “Add a graphic to increase your traffic!” (the kind of lingo that Lulu is an expert in). We gather too that the United States has become one large desert covered in wind turbines and solar panels, thanks presumably to global warming, but that life has gone on, and that people still enjoy sports, barbecues, and rock music, even if they don’t do too much with the written word any more. In this respect, Egan’s outlook is much less doom-and-gloom than Patchett’s.

The chapter gets its title from Alison’s brother Lincoln’s savant-like obsession with pauses in classic rock songs, like the ones in “Bernadette” by the Four Tops and “Young Americans” by David Bowie. This organic moment of interruption in songs—that are, by now, more than half a century old—stands charmingly as a foil to the unremitting modes of communication and media the children now live with. It appears that Lincoln is hunting for the song that will truly trick him in everyway possible, that will pause in a way that sounds like a false ending, but that will have really ended (another instance of infinitely delayed gratification). But the chapter ends with graphs mapping all the data that Lincoln has collected on these pauses, the length of the pause, its placement in the song, and so forth. This suggests that Lincoln has some need to understand these pauses scientifically, and that pleasure of data is, if not greater than, then at least equal to the pleasure of art.

I would argue that recognizing these dual pleasures is paramount for Egan as a writer, since it begins to explain our fascination with the constant information ticker of email, Facebook, and Twitter, as opposed to the slow trickle of themes and details that we find in a literary novel. Moreover, recognizing that these two pleasures can co-exist is the first step to being a “new hero” in the digital age.

It might be useful here to typify three literary “luddites.” There are the alarmists, like Ann Patchett. Then there are the collaborators, like Jonathan Franzen. Franzen has come out against Facebook and Twitter, and called e-readers “damaging to society.” But when he’s not polemicizing from a university lectern, Franzen is admitting, as he did in TIME, that the contemporary literary novel has to indulge in suspense and drama if it hopes to compete with television and the Internet. Sure, Richard Katz, in Freedom, voices Franzen’s criticisms about iTunes and the Internet with unmatchable wit and bitterness. And yet the entire novel’s resolution pivots on a cheap deus-ex-machina moment where Walter becomes a YouTube celebrity.

Egan is a saboteur, which, for a mainstream fiction writer, is quite a distinction. I don’t mean that Egan is going to take down the entire Internet with her work. Rather, she will find ways to seed new media with the humanist values of literature.

In a recent “Room for Debate” in the New York Times, novelist Jane Smiley stated that fiction will survive so long as our agency survives. “A work may only attract, never coerce,” she writes. “To read fiction is to do something voluntary and free, to exercise choice over and over each time the reader picks up a story or a novel.” It’s a nice idea, but perhaps too precious. What do we make, for instance, of a free speaking fiction machine, a Tweeting automaton storyteller like Lulu in Black Box? When information technology is folded into every aspect of our lives, can a story project itself into our brains without our even knowing?

Tim Wu and other scholars have recently been discussing the Constitutional protection afforded to computerized speech. If computers can speak, if they have language, can they also have literature? Not a spambot or a tweetbot, but a literary bot that, for instance, tweets a short story about a young female spy?

All of this sounds pretty sci-fi in its own right, but these are the kinds of questions that Egan’s recent work begs. I think it makes sense for writers like Egan who are strongly considering the junction between information technology and literature (one articulation of that compound, science-fiction) to be turning in a roundabout way to that genre.

In that same “Room for Debate,” on the future of fiction, James Gunn, the founding director of the Center for the Study of Science Fiction, said this of the genre: “The literary novel, a 20th century invention, continues its critical dominance as the only “serious” fiction. […] The most effective social documents these days are genre novels — crime novels, for instance, but particularly science-fiction novels that can make the world the protagonist, the background foreground. By isolating the issues of race, gender, sexual orientation, climate change, environment, governance, economics, catastrophe and whatever other problems the present embodies or the future may bring, science fiction can do what Dickens and Sinclair did, make real the consequences of social injustice or human folly.”

Like Egan, Gunn draws a correlation between science-fiction and the populist, serial works of the nineteenth century. The tropes of sci-fi can help us understand human issues; maybe a sci-fi mode of dissemination can, too.

Sci-fi, for Egan, might remain kind of a safe-zone at the moment, where she gets to explore both sides of this issue, the fate of literature, under the pretext that “this isn’t real, this isn’t realism” (after all, how many sci-fi predictions have been proven false?). But she does well to occupy this ambiguity. Patchett wants resistance on all levels, from readers, writers, and award committees, but is this resistance wise, or even possible, on the level of form? Polemic and stubbornness don’t always work well in serious fiction. And as realism starts to reckon more and more with technology and its own demise, and as it starts to get inflected by those realities, a whole new mode of literary sci-fi is sure to follow.

Max McKenna’s writing has appeared or is forthcoming in The Journal of Modern Literature, The Millions, Apiary Online, and Cartographer among others. He lives and works in Philadelphia.

This post may contain affiliate links.