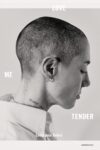

[Semiotext(e); 2012]

Tr. from Spanish by Michael Parker-Stainback

In 2005, through a strange set of circumstances, I ended up as an invited guest to the Angers Film Festival in Angers, France. That year’s Grand Prix du Jury was awarded to Le Cauchemar de Darwin (Darwin’s Nightmare), a film by Hupert Sauper that I initially thought was a polemical fake documentary about a set of interlocking horror stories set on the banks of Lake Victoria in Tanzania, each unleashed by globalization. This confusion was attributable in some measure to my poor French, but the larger issue was that I simply couldn’t bring myself to consider that what I was seeing on the screen had actually taken place.

At the center of the film are the devastating ecological consequences to Lake Victoria following the introduction of Nile perch, a fish coveted by European consumers. As the film traces this out into the social, economic, and political realms things go from bad to unimaginable. We learn that the planes exporting Nile perch fillets to Europe are importing weapons that fuel sectarian conflicts in the region. Factory owners exploit this political instability by overworking their employees in inhumane conditions (the legal economy), while the Russian and Ukrainian pilots pass their time doing drugs and often abusing local prostitutes (the quasi-legal economy). Add to this a spiraling AIDS epidemic, gangs of homeless and drug-addicted youth, and a food crisis at the heart of a thriving export market, and what you are left with is the condensation of our darkest suspicions about globalization. Darwin’s Nightmare happened to find one of those sites where these are unambiguously confirmed.

Sergio Gonzáles Rodríguez bravely documents a similar terrain in The Femicide Machine, but with one key difference that I’ll get to in a moment. Gonzáles Rodríguez is known by many as a columnist for the Mexican journal Reforma and as the inspiration for the character Sergio Gonzales in Roberto Bolaño’s 2666. The Femicide Machine, published as part of Semiotext(e)’s Intervention Series, attests to years of investigating the unsolved murders of hundreds of women in and around Ciudad Juárez, along with the institutionalized political, economic, and moral corruption that assures these crimes are committed with impunity.

Anyone who has read 2666 or is even marginally aware of the rampant violence in the state of Chihuahua understands that the scale of the problems are staggering. Since 1993 at least 400 women and girls have been killed, with roughly a quarter of the murders accompanied by evidence of sexual violence. However, Gonzáles Rodríguez’s own work uncovering the collusion between the police, government, the judiciary, and drug cartels probably means that the real figures are much higher and the brutality is much more extreme. The crisis of local authority runs so deep that the newspaper El Diario de Juárez ran a front page editorial in 2010 asking the various drug gangs “What do you want from us?”, meaning, What are the permissible stories which we can cover without fear of further journalists being murdered? Such are the demonstrations of “a lawless city sponsored by a State in crisis.” Lest we search for other explanations, Gonzáles Rodríguez reminds us, “the facts speak for themselves.”

The ambitions of The Femicide Machine are much broader than mere reportage. The book advances two intertwining theses that speak to the context of unrestrained violence. The first concerns Ciudad Juárez itself, where the placement of the maquilla (assembling plants) at the U.S. border rendered it a “city-machine whose tensions entwined Mexico, the United States, the global economy and the underworld of organized crime.” The second chapter, “Assembly/Global City,” describes this operation in great detail, including the city’s alienation from a functional and protective nation, as well as the a-socialization of any forms of civil society that might resist violence and disorder.

After establishing this urban and global context, Gonzáles Rodríguez advances his second thesis concerning the murders themselves. “Impunity is the murderer’s greatest stimulant,” he writes, and “the femicide machine, whose functioning has evolved over time, [has incorporated] judicial and political systems to such an extent that Mexican authorities have sidetracked or blocked the investigations . . . They seek to discount systematic and peculiar violence against women, a violence wherein organized crime and Juárez’s political and economic powers converge.” If we were to ask to whom Gonzáles Rodríguez’s many condemnations are aimed, it is primarily to these figures who cynically perform the failure of their own authority (police chiefs, judges, agents of the drug war, politicians, global capitalists). He caustically adds that as “authorities manipulated facts in order to avoid responsibilities; women were revictimized.”

Early in the book Gonzáles Rodríguez ominously wonders whether other femicide machines are gestating in Mexico and abroad. If we read Darwin’s Nightmare in a certain way, then the answer is, lamentably, yes — either work should be enough to shock our consciences. However, a tension emerges when we ask which metaphor is more appropriate: the one dealing with ecology and mutation or the one dealing with technology and the systemization of effects. The ecological metaphor speaks to the environing conditions that support certain forms of life while making others precarious. This might fit Ciudad Juárez, were it not “an ultra-contemporary technological enclave in the midst of a degraded environment.” If this is the case then even the grotesque mutations limning Lake Victoria definitively drift away from any self-correcting evolutionary mechanisms.

The tension between these metaphors will determine where we are likely to invest both our hopes and our indignation when we read a book like The Femicide Machine. There is also a question of which image fixes our attention in the first place. In the 20th century Theodor Adorno famously wrote that “to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.” More recently the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben has written about “the camp,” where “law and life” become indiscernible so that neither can produce legitimate restraints on the other. The Femicide Machine suggests that perhaps the referent for a new generation of writers (e.g. Roberto Bolaño, Valerie Martinez, Keston Sutherland) will be the slum, or the kind of urban conglomeration like Ciudad Juárez that systematically produces violence and misery at levels that Dickens would never have been able to imagine. That even biology cannot save us now is the gloomy possibility that The Femicide Machine places on the contemporary horizon.

This post may contain affiliate links.