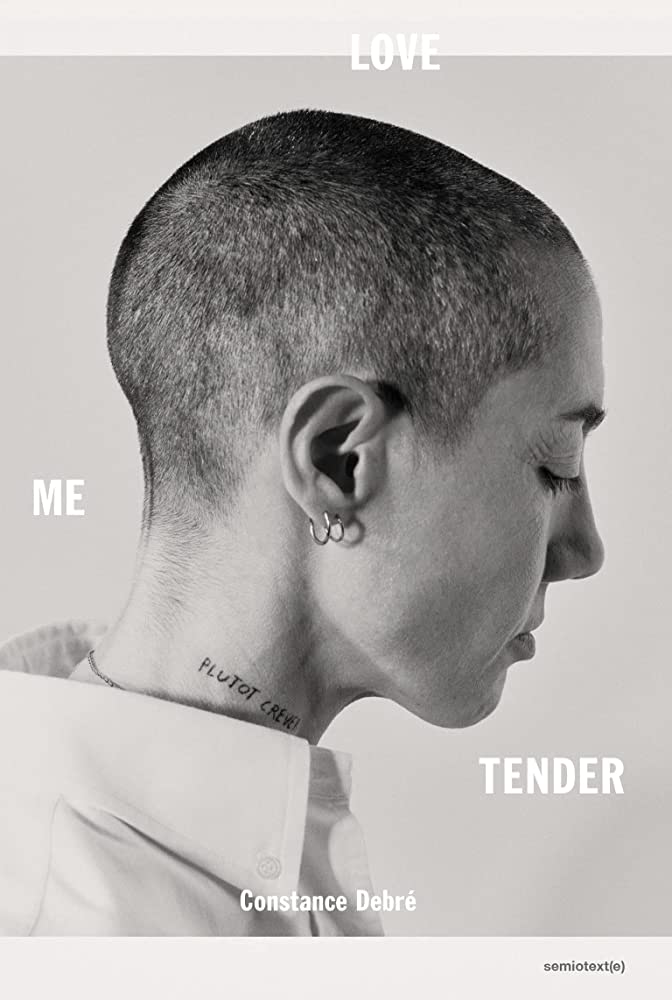

[Semiotext(e) / Native Agents; 2022]

In Constance Debré’s sharp new novel, Love Me Tender (Semiotext(e)), translated from the French by Holly James), a woman walks out on her life. She blows it up. After two decades of marriage, she leaves her husband, Laurent, and their eight-year-old son, Paul. She rents a tiny apartment, too tiny to fit her books. So she sells her book collection. Even the Duras. She quits her job as a lawyer. She writes full-time. For three years, she peacefully shares custody of her son with Laurent. “We do alternate weeks, all civil, we’ve never had any problems,” Debré writes. Their shared harmony ruptures when Debré tells Laurent that she’s dating women one night at dinner. Many, many women.

First published in France in 2020, Love Me Tender is a work of autofiction. The first-person narrator is also named Constance Debré, and the novel closely follows the author’s own experience of queer becoming; a becoming that transforms every aspect of her life, from her relationship with her son to France’s justice system. When Debré eventually asks Laurent for a divorce, he ignores her, then, sends a curt email: “Stop you’re turning on me.” Soon Laurent and Paul refuse to see her. A protracted custody battle ensues. Laurent seeks full custody, accusing Debré of incest and pedophilia. The implicit homophobia fueling Laurent’s claims is laid bare at a custody hearing. He shares a picture of Paul sitting outside on a terrace with one of Debré’s gay male friends. He quotes passages from gay authors Debré admires like Tony Duvert and Hervé Guibert. In the wake of losing her son, her grief blooms. It alters her worldview. She doubles down on her life as a “lonely cowboy.”

A modern-day coming-of-age story, our narrator doesn’t come out as a lesbian so much as become one, before us, page by page. She lops off her hair. She takes to wearing men’s shirts. She goes harder. To truly queer her life, she must remake it wholesale. “If I’d have settled for just liking women, it would’ve been fine,” Debré writes. “Lesbian lawyer, same life, same income, same appearance, same opinions, same ideals, same relationship to work, money, love, family . . . I didn’t go through all this just for more of the same.” In Love Me Tender, queerness is a disruptive force. Debré leaves her straight world behind: her nuclear family, her law career, and her financial stability. At the same time, she stumbles into an exciting new existence, all sex, cigarettes, and chlorine.

Swimming is a comforting constant amid the turmoil. “It’s my form of discipline, my method, my own form of madness to keep the madness at bay,” Debré says. Swimming, like writing, offers a reliable respite from her heartache. Her writing practice in particular has conditioned her for loss and loneliness. As a writer, she’s accustomed to leaving the world behind for hours a day to shift sentences around a page. Literature has not only primed her for loneliness but also seduction. Love Me Tender channels the performative masculinity of Paul B. Preciado’s Testo Junkie and the restless thirst of Jane DeLynn’s lesbian cruising novel Don Juan in the Village. In other words, Love Me Tender is hot.

Oscillating between loss and lust, Love Me Tender is a potent testament to the power of desire to propel us through times of despair. “A fuck is a fuck,” Debré tells us, referring to her lovers as “the girls.” “They don’t ask for much,” she writes. “Only my mouth my hands my ass.” Her sexual encounters aren’t always gratifying, but they help pass the time. The more girls she fucks, the more the line between love, desire, and killing time dissolves. “I’m learning that I can love anyone, desire anyone, come with anyone, be bored with anyone, hate anyone,” she writes. “I don’t see why it should have to be anything more than that, just love, just desire.” Debré rejects the capitalist and heteronormative impulse to extract value from her desires. For her, desire doesn’t need to yield bliss, produce love, or accrue into a successful relationship. Desire, like writing, is about the ride.

In Love Me Tender, desire does not cure Debré’s grief so much as throb alongside it, giving shape and meaning to her days. Desire to feel her muscles stretch and shake as she cuts through a blue pool of water. Desire when she sits down at her desk to write. Desire when she gets on her knees and sucks a girl’s dick. Throughout Love Me Tender, Debré reminds us that hunger is essential. Without desire how do we know we’re alive?

The narrator tells us that she upended her life “for the adventure.” She believes this is what makes her ex so mad. In the popular imagination, adventure is associated more with the cowboy than the cowboy’s mom. Throughout Love Me Tender, Debré skewers accepted notions of how mothers should be. In spare, unsentimental prose, she confronts the assumption that one cannot be both a mother and a lesbian. Instead, she shows how the experience of mothering gave her the courage to desire a new life. “It was so easy to be myself around [Paul],” she writes. “I might never have become a lesbian if I hadn’t been his mother first. I might never have dared.”

Debré’s refusal to conform to her culture’s accepted notions of motherhood and personal success costs her. For her, personal change has high stakes, and the experience of becoming someone else is as much about loss as liberation. Here, change is scary precisely because it can detonate our lives. By spotlighting both the terrors and pleasures of personal transformation, Love Me Tender offers a refreshingly honest and complex portrait of motherhood and midlife becoming.

Debré’s new life is necessarily simple. Grief has wizened her capacity to commit to anything more than swimming, fucking, and writing. “[I] reduce everything to simple gestures, then carry them out,” she says. She sleeps on a mattress on wooden slats. She owns only two pairs of jeans. She says, “There’s a certain joy that comes from doing things you didn’t think yourself capable of.”

She starts stealing. Sometimes she steals food, and other times, she does it “for the beauty of the gesture.” Some readers may pause at Debré’s romanticization of her newfound deprivation. Before her divorce, she worked as a lawyer, and she comes from a prestigious family. Later, when she reconnects with Paul, they stay at a family property. Her privileged status is perhaps what allows her to glamorize her purported poverty. But I also read her romanticism as a gesture of protective performativity. Who among us hasn’t tried to glamorize our losses? Who hasn’t embraced bravado in the face of grief?

The narrator of Love Me Tender may prefer to need nothing and no one. She may even fantasize about this ascetic life and call it freedom. But she can’t live out the fantasy. Though she tries. As her grief slowly lifts, she must shapeshift again. She meets a girl who she likes and stumbles upon another disruptive self-discovery: She craves connection after all. Tender love. “There aren’t that many different solutions,” Debré tells us. How will this connection alter her? In Love Me Tender, Debré shows us how desire is forever transfiguring our lives. We never stop becoming.

Elizabeth Hall is the author of the book I HAVE DEVOTED MY LIFE TO THE CLITORIS, a Lambda Literary Award finalist. You can find her on instagram at @badmoodbaby.

This post may contain affiliate links.