[Semiotext(e); 2022]

Tr. from the French by Jeffrey Zuckerman

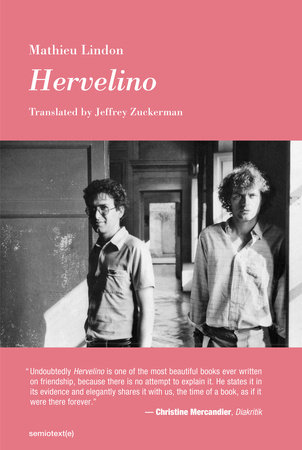

“Our names matter, those we have and those we claim,” remarks Mathieu Lindon at the beginning of Hervelino, a slim memoir of his friend Hervé Guibert, the French writer and photographer. Hervelino, a diminutive that evokes Italy, was Guibert’s nickname. He adored it, as he makes clear in an entry from The Mausoleum of Lovers, his posthumously published journals: “I melt when a friend (Bernard, yesterday, for the first time, and as though incidentally) calls me Hervelino.”

Of course, the names we have—and sometimes those we claim—are given to us. A name is a skein of relationships. The author’s own surname, in literary circles, was for decades synonymous with Les Éditions de Minuit, the celebrated independent publishing house founded in Paris in 1941. Lindon’s father Jérôme was its longtime director, responsible for seeing into print an astonishing number of venerated French-language writers, among them Samuel Beckett, the Nouveau Roman authors, Marguerite Duras, and Marie NDiaye. Upon his death in 2001, Lindon’s sister Irène became the director.

Born into a literary household (“Sam” and Alain Robbe-Grillet were regular guests), Lindon wanted to write from a young age, and it followed, or so it seemed to him, that his father would publish his fiction. He was correct, in a way. His first novel, Nos plaisirs, a cheerily perverse satire of family life, did come out with Les Éditions de Minuit, but Jérôme insisted he use a pseudonym—not, as may be expected, to avoid the impression of favoritism, but because the rest of the Lindon family might have disapproved of the characters’ amoral attitude to transgressive sex. Your name matters a great deal, it turns out, if you come from a patrician line of magistrates and industrialists. Since then, Lindon has published some two dozen books under his own name, exchanging Les Éditions de Minuit for another celebrated publishing house, Éditions P.O.L. In recent years, his writing—which was once characterized by Guibert as a “game of character assassination”—has taken a compassionate, autobiographical turn. His most recent book, published in France in January, was Une archive, a personal history of Les Éditions de Minuit.

In 2011 Lindon won the Prix Médicis, one of France’s major literary prizes, for Learning What Love Means (published in English by Semiotext(e) in 2017), to which Hervelino is a companion piece. A memoir of his father and Michel Foucault, a friend and mentor, Learning What Love Means is the sentimental education of a young gay man. It is also a treatise on filiation and affiliation. Lindon’s father, for all his intelligence, high-mindedness, and radical taste, comes across as a stern, buttoned-up man. By contrast, Foucault is a model of attentiveness and unostentatious generosity. It was Foucault who, defusing the friction between father and son, gave Lindon the pseudonym for his first novel: Pierre-Sébastien Heudaux. (The witty solution appealed to Lindon: rendered P-S. Heudaux, the name is a play on “pseudo.”) Though he’s nearly the same age as Jérôme, Foucault is decidedly not a surrogate father figure; rather, he’s the antithesis of a father, “inventing new bonds of love and sex, bodies and feelings.” In a rare reference to the philosopher’s writings, Lindon suggests Foucault retained from his work on power the singular capacity to forge mutually rewarding relationships. He was, as Lindon puts it, invoking Guibert, “the friend who saved my life.”

Much of Learning What Love Means takes place at Foucault’s apartment on the rue de Vaugirard in Paris, often when the philosopher is lecturing abroad. The gathering spot for a circle of young gay men, the apartment provides a fairy-tale setting for conversation, dinner parties, hookups, and frequent LSD trips. There, in the summer of 1978, Lindon meets Guibert. The latter—impossibly handsome, earnest, abstracted—is Foucault’s neighbor. His books, too, come out with Les Éditions de Minuit, until he and Jérôme have a falling-out. Lindon and Guibert quickly become fast friends. Their circle is stunned by Foucault’s death from AIDS in 1984. Guibert died not long after, in 1991. It’s only now, late in life, that Lindon feels capable of writing about this period.

Since his bonds with Guibert and Foucault are inextricable, Hervelino revisits some of the material in Learning What Love Means. The title is Lindon’s way of gently reclaiming his friend, whose posthumous fame (thanks in large part to Semiotext(e), who in recent years has published or republished English translations of many of his best works) has amplified his genius for nonchalant self-invention. “Everyone calls him Hervé now,” Lindon notes, bemused by the presumptuous familiarity. He associates the nickname specifically with the two years they spent in Rome, where they had overlapping residencies. Like in Learning What Love Means, an apartment serves as both inner sanctum and sepulcher: instead of the rue de Vaugirard, the setting is the imposing Villa Medici in Rome, which houses the prestigious, state-sponsored French Academy. The men are no longer young, but a similar atmosphere of freedom and exuberance prevails, and a similar grief looms ahead. The French Academy represents for Lindon the culmination of his friendship with Guibert. By then, Guibert’s writing was already entwined with his life story, or some version of it; in Rome, his work became irrevocably bound up with his death.

Guibert learned he was HIV-positive during his residency there, whereupon he wrote To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life (1991), a roman à clef in which he candidly chronicles Foucault’s death and his own wasting away from the disease. Hervelino covers much of the same period as that searing book, and readers will recognize the Villa Medici—“this citadel of misfortune”—as well as David—that is, Lindon. Death overshadows their cloistered Roman world. Yet Lindon is caught off guard whenever he’s reminded of Guibert’s sick body, and the sexual politics urgently at issue, even after reading To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life. “AIDS wasn’t a label I attached to Hervé or to his work before his death,” he says. His obliviousness, which for the most part appears to be deliberately exaggerated, holds the sorrow at bay, most of the time. When it does well up, it usually has a quieting effect. In these last years of his life, Guibert is frenetically productive, “seized with the desire to write every possible book—all the ones I’d hadn’t written yet, at the risk of writing them badly.” Lindon, meanwhile, writes nothing.

Hervelino is Lindon’s recollection of the moments they spent in each other’s company: hanging around the Villa Medici, going to countless restaurants in Rome, walking through the magnificent Borghese gardens, buying CDs. The stuff of their friendship is presented with a moving matter-of-factness. Ominously, Guibert takes regular trips back to Paris—during which, as we know from To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life, he has a series of distressing consultations with doctors—and they visit the island of Elba, where Guibert wished to be buried. Throughout, Lindon is unapologetically idle; his pettiness toward some of the functionaries and other residents hearkens back to the character assassination of his early novels.

Loosely collaged together, these memories are recounted in an autumnal style, immaculately translated by Jeffrey Zuckerman: unshowy, amiably meandering, sprinkled with clichés and silly rhymes. In addition to the many gaps in his memory, which he acknowledges, Lindon doesn’t dare write about certain subjects. Anything that Guibert wrote about, for instance, is off limits—and Guibert fairly dissected his own life. Such are the difficulties of remembrance that Lindon at one point despairs: “a book about Hervé, I just can’t do it.” He seems, at times, to have written the book despite himself.

In reviving Hervelino for a little over one hundred pages, Lindon is guided by the lessons of Learning What Love Means. He takes fastidious care not to lay a claim on his friend. Though he references Guibert’s work, drawing on his firsthand knowledge of the manuscripts, he doesn’t presume to have any insights. When asked in Rome about the prospect of becoming Guibert’s literary executor, he bluntly expresses ambivalence. Une archive begins with a similar anecdote, about the prospect of writing a biography of his father. Indeed, Lindon’s distrust of authority—of anyone he considers a “colonizer”—is so profound it risks torpedoing his own project. “In what way do I have a right to speak?” he asks himself in Hervelino. “I don’t.” Neither a biographer nor a literary executor, Lindon deftly sketches relationships as they mature, change, and generate new relationships. Through writing, he brings together the people he loves, some of whom never had the chance to meet: Guibert and Foucault are again joined in Hervelino by Corentin, a teacher, and Rachid, a Moroccan novelist, who both also appeared in Learning What Love Means. Cutting across generations, social classes, and racial identities, these life-giving relationships continue to be instructive.

For an elegiac work, Hervelino has little in the way of lamentation or solace. “Death was there, there was no theorizing it or solving it,” as Lindon succinctly puts it, shortly before exhausting his memories of the Villa Medici. We are left, rather abruptly, with some of the material traces of their friendship. During his lifetime, Guibert had given Lindon an inscribed copy of each of his books, from Suzanne et Louise (1980) to Vice (1991). These eighteen inscriptions are reproduced in facsimile in chronological order as an appendix, with explanatory notes. Full of inside jokes, the messages themselves—often dedicated to Mateovitch, Lindon’s nickname—don’t add all that much to the foregoing text. They attest, plainly and powerfully, to a long-lasting intimacy, to a life of writing, shared. (A degree of immediacy is lost in translation: The reader of the French edition must decipher Guibert’s handwriting, which gives those pages an extra poignancy.) From Guibert’s first year in Rome onward, the inscriptions are just declarations of love, repeated over and over. Hervelino is, in a sense, an extended gloss on these short, affecting lines. To Hervelino, from Lindon, with love.

Louis Lüthi is the author of On the Self-Reflexive Page II (Roma Publications, 2021). He teaches at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

This post may contain affiliate links.