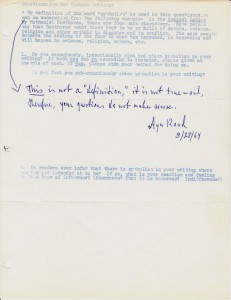

Last week, the Paris Review blog published a really great piece about “The Symbolism Survey,” a set of questions mailed to prominent authors in the early 1960’s. The questions were sent by a sixteen-year-old high school student named Bruce McAllister who had grown fed up with searching for symbolism in the high school canon (leave it to a sixteen-year-old to follow through with a mind-numbingly tedious endeavor just to prove a point to an English teacher). The fact that authors responded, some with insight and patience (Ralph Ellison, Ray Bradbruy) and others with dismissal and priggishness (Jack Kerouac and Ayn Rand, obvi), didn’t surprise me in the least. When asked why the authors responded to a high schooler who had misused (fittingly) the word “precocious” in his introduction letter, McAllister reflected, “The conclusion I came to was that nobody had asked them. New Criticism was about the scholars and the text; writers were cut out of the equation. Scholars would talk about symbolism in writing, but no one had asked the writers.”

Last week, the Paris Review blog published a really great piece about “The Symbolism Survey,” a set of questions mailed to prominent authors in the early 1960’s. The questions were sent by a sixteen-year-old high school student named Bruce McAllister who had grown fed up with searching for symbolism in the high school canon (leave it to a sixteen-year-old to follow through with a mind-numbingly tedious endeavor just to prove a point to an English teacher). The fact that authors responded, some with insight and patience (Ralph Ellison, Ray Bradbruy) and others with dismissal and priggishness (Jack Kerouac and Ayn Rand, obvi), didn’t surprise me in the least. When asked why the authors responded to a high schooler who had misused (fittingly) the word “precocious” in his introduction letter, McAllister reflected, “The conclusion I came to was that nobody had asked them. New Criticism was about the scholars and the text; writers were cut out of the equation. Scholars would talk about symbolism in writing, but no one had asked the writers.”

The survey resurfaced on the same day Full Stop editors were about to launch our own questionnaire for writers (lovingly adapted from a 1939 survey in the Partisan Review), The Situation in American Writing. While criticism has shifted away from a cult of the critic to an almost constant appraisal and derision of the private and public lives of the writer (we have some of the respondents to the symbolism survey to thank for that), it still seems important to ask pointed questions to the writers themselves. Some responded to our own questionnaire with a quick dismissal — one writer told us the questions were too “serious” — and others declined because they thought the questions themselves were irrelevant.

The prevailing idea that an artist’s work speaks for itself isn’t contradicted by the basest of interviews — the survey — but it could be another canvas on which to paint. Each author is reflected on a set of non-participatory inquiries — if an author chooses to go a certain direction with a question, there’s no interviewer there to rein them in. They are free to explore whatever they choose to. And that’s the beauty of the survey — it is the charity of the writer that serves to complete the effort. You trustingly send this thing blind into the world hoping it will be given eyes by the people you respect, and those who aim to “inspire tenderness” tend to respond with insight and humor.

Unless they’re Ayn Rand.

This post may contain affiliate links.