The Beach Beneath the Street by McKenzie Wark, Verso, 2011, 224 p.

Thinking the Impossible by Gary Gutting, Oxford University Press, 2011, 240 p.

In our latest installment of “How to Master x in Two Weeks” Michael Schapira takes us back to Paris’ Left Bank in the 1960s. You can find part one, a breakdown of the culture wars, here, and part two, an analysis of your crappy job prospects, over there.

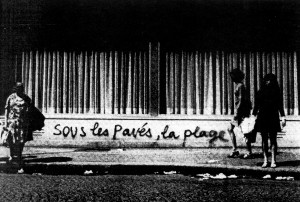

I must confess to suffering from some pretty serious 1968 romanticization – and despite inspiring recent student protests in California, Chile, London, and New York, the soixant-huitards of Paris remain my preferred model for youth protest movements. Why this is so is captured in two recent works that look back to the cultural ferment that allowed the movement to proceed along such interesting political, artistic, and philosophical paths. In The Beach Beneath the Street McKenzie Wark revisits the “glorious times” of the Situationist International, a “small band of artists and writers whose habits were bohemian at best, delinquent at worst, who set off with no formal training and equipped with little besides their wits, to change the world.” And while Guy Debord and the Situationsits were trying “at the very least to build cities, the environment suitable to the unlimited deployment of new passions,” those in the universities were busy doing what Gary Gutting titles his history of French philosophy since 1960, Thinking the Impossible. What’s more, as we see on Gutting’s cover, men are doing this in suits, women in sexy shawls, and each serving as the most effective cigarette advertising campaign that I’ve ever been exposed to (I challenge you to watch Breathless and not crave a smoke afterwards).

As Wark says in his conclusion to The Beach Beneath the Sreet, there is a 60s to suit every taste, including that of a disaffected and cynical generation in the first decades of the 21st century. We could, for example, look back on the 60’s as the final burst of youthful fancy before the cold reality of neoliberalism was set upon any form of utopian thinking. One of Wark’s riffs on high and low theory (a stylistic choice which is bound to miss its mark from time to time) captures this well: “Hegel’s owl of Minerva no longer flies at dusk, because the shotgun of Dick Cheney fired at first light.”

Yet Wark’s book is after something quite different, and its strongest aspect is linking a central task of the Situationist International with our present poverty of imagination. This is the problem of finding the right mode of remembrance that allows us to carry forward the new possibilities opened up in situations, whether they be revolutionary, like ’68, or experiments in everyday life such as the ones that the Situationists and other radical artistic movements pursued with such creativity in the 60s. If the task for the most extreme utopian thinkers of the movement was to figure out how to remember something like May ’68 in writing soon after the event (René Viénet writes that “people strolled, dreamed, learned how to live”), Wark is right to say that “our problem today is how to remember that remembrance.”

A very similar problem sits behind Gary Gutting’s otherwise more academic treatment of this period. Writing of a division which will be familiar to students of modern philosophy – the analytic/continental divide – he states that “French philosophy since the 1960s is an important resource for those who, often rightly, see analytic philosophy as lacking in a certain sort of intellectual imagination and too constrained by deference to the banalities of obvious truths.”

Gutting’s thesis is that the major philosophers of the era (Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault, Giles Deleuze, Emmanuel Levinas, and Alain Badiou) “faced up to questions about the limitations of conceptual thought,” a decision which has brought derisive charges of obscuritanism from most Anglophone philosophers (“if it can’t be conceptualized, then what are we talking about”), but to more sympathetic audiences marks path-breaking advances in our thinking about ethics, politics, aesthetics, and the practice of philosophy itself. Like the task of the Situationists, these philosophers were adamant on finding a form of expression able to challenge reigning standards of discourse.

The two books actually share a similar structure, each beginning with a detailed contextual sketch of where these people came from and then moving thematically through some key concepts of the period. Wark escorts us around Saint-Germain through the experimental films of Isadore Isou; the trysts between dancers, musicians, and artists; and the tightrope act of bohemians attempting to avoid the post-war Bourgeoisie and Stalinist alternatives that caught most young people. Gutting begins his book with a very informative account of the French educational system that decisively shows how French philosophers retain a vital link with the history and standards of their discipline, contra the charges of loose thinking mentioned above. Together these introductions show the mixture of academic, artistic, and public life that makes France the envy of many to this day. And even if their paths diverge after this – Wark taking up key Situationist themes of dérive, potlatch, détournement, unitary urbanism and Gutting showing how these philosophers related to their progenitors through chapters on Hegel, Heidegger, Sartre, and Nietzsche – both portraits are really of a piece and capture well the extraordinary nature of this period.

The biggest takeaway from these books is not to romanticize an artistic or intellectual scene, but rather to face up to the question of cynicism that hangs over the present. Wark hopes that reacquainting ourselves with the Situationist International gives us the opportunity to take two steps back (to a period of radical possibilities, or unrealized utopias) in order to take three steps forward. He accomplishes this by not “[reducing] a movement to a biography,” but by showing the movement in its staggering and sometimes contradictory variety. Gutting gives us a strong example of what it looks like to develop a language that addresses the things that are most important to us, but which the current conceptual landscape doesn’t give us many opportunities to speak about. Paris of the 1960’s should by no means have an exclusive hold on attempt to imagine things otherwise, but forty years on still cuts one of the most attractive figures in recent history.

This post may contain affiliate links.