by Matt Orenstein

“I just wanna stay in the garage all night”

– The Clash

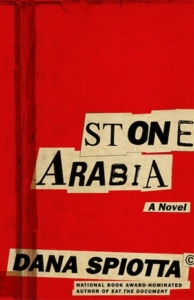

The older I get, the easier it is to hear the shades of fear in rock songs. When you’re 13 and you hear Roger Daltrey sing “Hope I die before I get old,” you hear “I wanna stay young forever!” At 23, after ten years of playing in bands and surviving puberty, it sounds more like “getting old scares me to death.” Rock music plays a pivotal role in Dana Spiotta’s Stone Arabia – siblings Nik and Denise, the central characters, spent the most formative parts of their formative years haunting the music scenes on the Sunset Strip. Nik was the musician, Denise the loyal fan. As they get older, they struggle to grapple with the inevitability of aging: Nik deliberately loses himself in his pop songs and in composing his own fictional autobiography (I’ll get to that) to keep his failures at bay, while Denise buckles under the weight of both her world and the world at large. It’s a comfort that the two have stayed close through so much, but less so that neither one is equipped to actually help the other. Instead of being a feel-good story about the unbreakable bond between siblings, or about rock music’s healthy catharsis, Stone Arabia is about dealing with the subtle terror of growing old.

“Garageland,” the song from Stone Arabia’s epigraph, might as well be an anthem for Nik. It’s about more than just staying in the garage all night: it’s about a doing so in spite of everything outside. That’s what keeps Nik in the garage. That, and his job at a local bar is far from stimulating. Nik has been in the garage (or, rather, his home studio) since his postpunk band broke up, and he has written and recorded countless albums spanning just about every swath of pop music he knows. He distributes his albums to a very small fan base comprised of ex-bandmates, ex-girlfriends, Denise and her daughter Ada. His creative output rivals only Robert Pollard’s, as does his gift for naming his projects (The Fakes, The Pearl Poets, to name a couple). He’s content to keep his audience small, in part, because he mostly makes music for his own fulfillment. Even when Ada makes a documentary about his life, he seems nonplussed. He humors her and goes along with it because he’s already done enough to satisfy himself.

If it were as simple as saying that Nik’s DIY ethos was all defiance and liberation, old age be damned etc., Nik would be a caricature. But in Nik, Spiotta deftly teases out an uglier aspect of embracing obscurity: narcissism. Doing things yourself because you’re too proud or afraid to ask for help. In rock & roll of all kinds the zeitgeist/ mythology is equally important as the music (though it matters less and less as the digital age keeps on), and Nik has spent at least as much time self-mythologizing as he has making records. Since his adolescence, he’s kept over thirty volumes of interviews, newspaper and magazine features, reviews (both pans and raves), letters to and from him. Dubbed The Chronicles, this fictional autobiography spans over thirty years of his life. Denise puts it nicely: “his whole life is a private joke he doesn’t want to explain to anyone.” Spiotta could spin The Chronicles into a whole other novel, but I wouldn’t wish that on her or anyone else. The Chronicles reads like fan fiction, with clichés dutifully cribbed from The LA Times, Creem, and Rolling Stone. Though it’s a masterful satire of music fandom and the DIY ethic, it works best in the small dose we’re given. As self-indulgent as The Chronicles is, it’s also Nik’s concession that his life didn’t quite unfold as he wanted. Creating this fictional version of himself allows him a chance to escape from the one that didn’t get famous, the one who gets older. Eventually, though, it stops working. The harder he pushes fifty, the harder it becomes to lose himself in The Chronicles. When he hits fifty, he finally breaks.

While Nik obsessively curates his imagined past, Denise has trouble remembering her real one. A hypochondriac with web-MD tendencies, Denise manages to convince herself that she is losing her memory as she gets older. This scares her more than Getting Old in the abstract. Her musings about Memory often wax Màrquez-lite: our memory is what keeps us grounded, so as it goes we go. While Nik seems to have accepted this, even reveled in it, Denise’s fight for her memory is what ultimately endears her as a central character.

Entertaining (and infuriating) as Nik is, Stone Arabia belongs to Denise. She narrates a significant portion of Stone Arabia, and the third-person narrator generally corroborates Denise’s story. Though she surrounds herself with fetishists and kitsch-obsessives (her boyfriend’s fixations are Thomas Kinkade and James Mason), she’s the only character in the novel without some bizarre attachment to the pop culture of yesteryear. Her fixation is instead on the present. She’s driven to dizzying hysterics by the horrors she sees on the News – from mothers taking babies into bars, to Abu Ghraib. “I had, in middle-age, become someone whose deepest emotional moments happened vicariously,” Denise says, and it’s true. Even her mother’s onset dementia fails to provoke the same kind of emotional response that she has when she sees a news story about an abducted Amish girl in upstate New York. Upon seeing that her first celebrity crush – Garret Wayne, child star – shot his family and then himself, she thinks: “How shameful, how awful, to hear a about a tragedy and relate it to my vanity and insecurity about aging.” Unlike Nik, Denise invests herself in affairs beyond her own life, and unlike Nik she doesn’t shy away from her fate to age like the rest of us. But it still terrorizes her at every turn.

It’s been over fifty years since the dawn of rock & roll. Even though its Peter Pan complex still surfaces in many artists’ repertoires, there are more and more artists who imbue this seemingly ageless music with their own experiences of getting older. There are others who try valiantly to appear young: the results are comic at best, discomforting at worst. Long Tall Sally has become Baby Jane, and in Stone Arabia Spiotta explores exactly what that means. Her portraits of kitsch-mongers next to that of Denise’s pragmatism make for some savagely entertaining satire. Underneath that satire, though, there’s the foreboding reminder that we’re going to get old, and there’s nothing we can do.

This post may contain affiliate links.